From Missing Bodies to Stolen Faith: The Three Pillars of Pakistan’s Civil Decay

A state that relies on disappearing its citizens, disenfranchising its minorities, and outsourcing its justice to religious mobs is a state in retreat from the modern world.

Amidst the complex landscape of South Asian geopolitics, Pakistan finds itself at a precarious crossroads where the traditional boundaries of law and statecraft are increasingly blurred by shadow policies and the instrumentalization of religious sentiment.

As of early 2026, the structural integrity of Pakistan’s social contract is under unprecedented strain. The state’s reliance on extrajudicial mechanisms to manage dissent, coupled with a legislative environment that increasingly narrows the definition of a “citizen,” has created a cycle of instability that transcends simple political friction.

To understand the current crisis, one must look at the three pillars of this systemic decay: the normalization of enforced disappearances, the institutionalization of religious repression, and the calculated weaponization of faith as a tool of political and social control.

The Shadow State and the Silence of the Disappeared

The phenomenon of enforced disappearances has evolved from a sporadic counter-insurgency tactic into a standardized instrument of state governance.

Throughout 2024 and 2025, reports from the Human Rights Commission of Pakistan (HRCP) and international monitors like Amnesty International have painted a grim picture of a “culture of impunity” that operates beyond the reach of the judiciary.

In Balochistan alone, the numbers are staggering; data from November 2025 indicated at least 106 new cases of enforced disappearances in a single month. This is not merely a regional security issue but a nationwide crisis of constitutionalism.

The human face of this crisis was most vividly captured by the Baloch Long March and the subsequent leadership of activists like Mahrang Baloch.

In late 2024, the targeting of women activists marked a disturbing escalation in the state’s crackdown. The “kill and dump” policy—a term now synonymous with the discovery of mutilated bodies of formerly disappeared persons—continues to terrorize marginalized communities.

Despite the 2024 United States Department of State Human Rights Report highlighting these “unlawful or arbitrary killings,” the domestic response has been largely performative.

The Commission of Inquiry on Enforced Disappearances (COIED), established to address these grievances, has been widely criticized by civil society as a “clearing house” for state narrative rather than a mechanism for justice.

Families of the missing, many of whom have spent over a decade in protest camps, find themselves trapped in a legal vacuum where the state neither acknowledges the detention nor produces the body, effectively erasing the individual from the legal record.

Institutionalized Repression: The Shrinking Space for Minorities

While the shadow state deals with political dissent, the legislative state has been busy refining the machinery of religious repression.

In Pakistan, faith is not a private matter of conscience but a public marker of legal status. For the Christian and Hindu communities, 2024 and 2025 have been years defined by a terrifying “weaponization of the womb.”

In Sindh, where over 90% of the Hindu population resides, human rights groups estimate that over 1,000 minority girls are forcibly converted and married off each year.

A harrowing case in June 2025 involved the abduction of four Hindu siblings—including a 14-year-old boy and a 16-year-old girl—from their home in Shahdadpur. Within 48 hours, forced videos were circulated online to “validate” their conversion, a tactic increasingly used to bypass legal scrutiny.

The Christian community remains similarly besieged. Following the horrific Jaranwala violence of August 2023, the subsequent years have offered little justice. As of late 2025, despite over 5,000 people being initially accused of burning 26 churches and 80 homes, convictions remain virtually non-existent.

Instead, the judicial system has seen cases like that of Shagufta Kiran, a Christian woman sentenced to death in September 2024 for allegedly sharing “blasphemous” material in a digital chat group.

This environment of selective justice ensures that while the mob remains free, the minority victim remains incarcerated or in hiding.

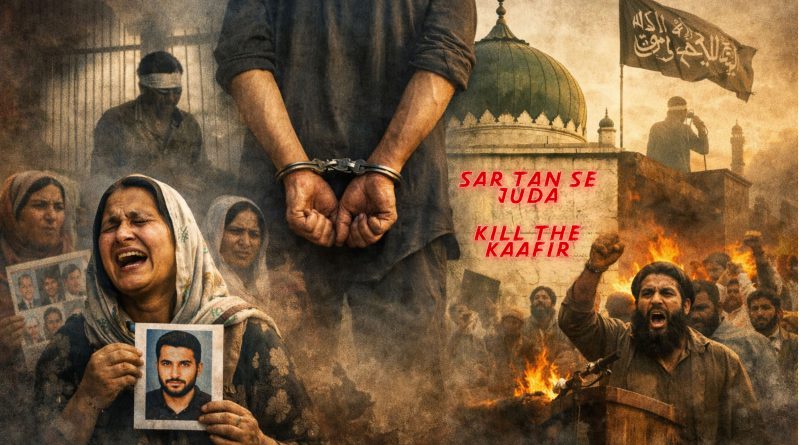

The Blasphemy Industrial Complex and the Weaponization of Faith

The most volatile element of this triad is the weaponization of faith through the country’s blasphemy laws. What were once intended as colonial-era protections against communal disharmony have been transformed into a “blasphemy industrial complex.”

In 2024, the HRCP estimated that over 750 people remained in prison on blasphemy charges, many of them languishing for years without trial.

However, the most dangerous development in 2025 has been the emergence of what activists call “blasphemy gangs”—organized groups that use social media to entrap individuals, particularly the youth, in fabricated religious controversies to extort money.

This weaponization has led to a total breakdown of the rule of law in instances of mob violence.

The lynching of a man in police custody in Quetta in September 2024, and the subsequent “encounter” killing of a doctor in Umerkot by police officers after he was accused of blasphemy, illustrate a terrifying trend: the state is no longer just failing to protect the accused; its agents are actively participating in the summary execution of those accused of religious offenses.

When the state itself adopts the logic of the mob, the judicial process becomes a mere formality. The Tehreek-e-Labbaik Pakistan (TLP) and similar groups have successfully shifted the “Overton window” of Pakistani politics, making it political suicide for any mainstream leader to suggest reform of these laws.

The consequences of this three-fold crisis are clear. A state that relies on disappearing its citizens, disenfranchising its minorities, and outsourcing its justice to religious mobs is a state in retreat from the modern world.

The analytical consensus for 2026 suggests that unless there is a fundamental shift toward civilian supremacy and a genuine commitment to pluralism, the internal contradictions of the Pakistani state will continue to manifest in cycles of violence and international isolation.

The path forward requires more than just legislative reform; it requires a dismantling of the security paradigm that views its own citizens as the primary threat to national integrity.

Disclaimer: Views expressed by writers in this section are their own and do not reflect Milli Chronicle’s point-of-view.