Down Memory Lane: 7 November 1975 in Bangladesh

The damage inflicted upon Bangladesh by Zia, Ershad, and Khaleda is immeasurable. They desecrated the very ideals for which millions died.

7 November 1975 — a date seared into my memory. I was then a senior student at Dhaka University, residing in Sergeant Zohurul Haque Hall (SZHH). On the evening of 6 November, my close friend and classmate, Zamal Fazle Rubby Badal — a prominent member of the Gono Bahini, the armed wing of the Jatiya Samajtantrik Dal (JSD) — came hurriedly to my room, which adjoined his. “Tonight, something big will happen in Dhaka under the leadership of JSD,” he whispered, his voice charged with excitement. I pressed him for details and promised secrecy, but he refused to reveal more.

At around 11 p.m., I retired to bed, unaware of the storm about to break. Shortly after midnight, I was jolted awake by loud slogans echoing from the ground floor of SZHH — cries proclaiming that a “revolution” had erupted in Dhaka Cantonment and across the nation. Curious and uneasy, I went downstairs to find a large procession, led by JSD’s student wing and Gono Bahini members, chanting at the top of their voices that JSD had seized power in Bangladesh with the backing of the army.

All through the night, they marched from hall to hall, through the Dhaka University campus, shouting revolutionary slogans. Some processions even advanced toward the Dhaka Cantonment. I watched everything unfold, a silent witness to the beginning of chaos.

As dawn broke on 7 November, the air was thick with frenzy. Loudspeakers blared across the campus, announcing that retired Colonel Abu Taher was now the supreme leader, and under his command, General Ziaur Rahman had been freed from house arrest. The JSD cadres declared that Colonel Taher, General Zia, and other senior leaders would address the nation from the Central Shaheed Minar that very morning.

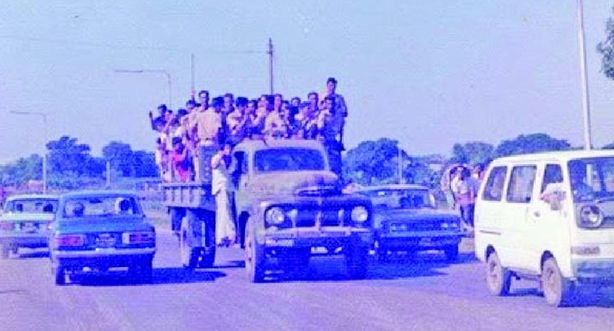

Along with friends from SZHH, I made my way toward the Shaheed Minar. On the way, we saw hundreds of military trucks and tanks filled with soldiers, chanting slogans — “Sepoy-Janata Zindabad,” “Gen. Zia Zindabad,” “Col. Taher Zindabad,” and “JSD Zindabad.” The Shaheed Minar ground was already teeming with thousands of people. Before 7 a.m., it was overflowing — a sea of civilians, soldiers, tanks, and convoys.

Although I was never aligned with JSD’s politics, I stayed there as an observer, curious to witness history unfold. A makeshift podium had been erected, and JSD leaders kept assuring the restless crowd that their revolutionary leaders would soon arrive to address them.

But around 11 a.m., a contingent of soldiers, loyal to General Zia, suddenly stormed the ground with tanks and opened fire on the podium. Panic swept through the crowd. My friends and I ran desperately back toward SZHH. Behind us, we heard screams and the sickening sounds of gunfire — countless lives cut short in minutes. When we finally reached the hall, gasping for breath, we knew we had narrowly escaped death. How many died that morning, I cannot say, but the rift between Colonel Taher and General Zia had already turned lethal.

General Zia, having been freed from confinement by Colonel Taher’s loyal soldiers, had initially embraced him and said, “Taher, you have saved my life. I am now at your disposal.” Yet soon after, he betrayed Taher. When asked to appear at the Shaheed Minar beside his saviour, Zia refused. That refusal marked the beginning of Taher’s tragic end — and Zia’s ascent as the chief architect of betrayal.

To look back now is to remember that Colonel Abu Taher was a true patriot — a man of courage, integrity, and immense love for his country. He had defected from the Pakistan Army in 1971, joined our Liberation War, and fought valiantly on the front lines, losing a leg in battle. He was one of the valiant sector commanders who led from the front.

After independence, Colonel Taher voluntarily retired from the Bangladesh Army while serving as Commander of Cumilla Cantonment. Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman later appointed him as Director of the Narayanganj Dredger Directorate. His deputy there was Engineer Ziauddin Khan — “Ziauddin Bhai” to me — a brilliant BUET graduate and a man of deep patriotism who had fought in the Liberation War.

I had the privilege of working with him years later, between 1981 and 1984, when we shared an office. We bonded deeply over our shared ideals. He loved me as his younger brother and always spoke with reverence of Colonel Taher — his honesty, his administrative acumen, and his unwavering commitment to the nation.

Ziauddin Bhai never knew of Taher’s deeper involvement in JSD politics, and when the news of his hanging came, he was devastated. It was incomprehensible to him that such a noble soul could be condemned by the very nation he had helped to free.

Colonel Taher hailed from Netrokona, close to my own home district of Kishoreganj. His father-in-law, Dr. Mohiuddin Ahmed — a respected physician — was a close friend of my father. Taher used to visit Dr. Mohiuddin’s home, only ten minutes’ walk from ours, and I met him there several times. He spoke in fluent English and often advised me to become a good citizen, though he never discussed politics. Had I known then of his involvement with JSD, I would have pleaded with him to stay away from its treacherous orbit.

Taher’s unyielding principles and moral clarity ultimately became his undoing. The JSD exploited his patriotism to advance its lust for power. He became their tragic pawn — and paid for it with his life.

Colonel Abu Taher was a true patriot — a man of high moral standing and indomitable courage. And for that very reason, he was falsely framed and executed by the ruthless and unlawful regime of General Ziaur Rahman — a betrayal that remains one of Bangladesh’s darkest chapters.

Indeed, it was Zia who fractured a once-united nation. He brought back the collaborators — those who had aided Pakistan’s genocide — from disgrace to power. There had been no public demand to rehabilitate them, yet Zia displayed audacious arrogance in doing so.

He freed notorious war criminals from prison, restored the citizenship of fugitives, and paved the way for Golam Azam — the local architect of mass murder — to return under Pakistani protection. During Khaleda Zia’s first government, Golam Azam was finally granted full Bangladesh’s citizenship — a national shame.

Zia made Shah Azizur Rahman, a wartime collaborator, Prime Minister of Bangladesh. He brought Abdul Alim — later convicted of genocide by the International Crimes Tribunal — into his cabinet. His widow, Begum Zia, followed the same sordid path, appointing convicted war criminals Matiur Rahman Nizami and Ali Ahsan Mujahid as cabinet ministers.

The damage inflicted upon Bangladesh by Zia, Ershad, and Khaleda is immeasurable. They desecrated the very ideals for which millions died. They opened the floodgates to communalism, corruption, and moral decay.

These were not leaders — they were desecrators. They poisoned our national soul with medieval darkness, empowering the defeated forces of 1971 to reemerge from the shadows. They were the ghosts of betrayal — ghouls whose insatiable appetite for power and depravity defiled our sacred land.

They created a moral wasteland where the spirit of 1971 was mocked, and vice, greed, and cruelty ruled supreme. Their perfidy remains unforgivable.

Their mendacity is unpardonable.

Disclaimer: Views expressed by writers in this section are their own and do not reflect Milli Chronicle’s point-of-view.