As India’s electrical grid strains, rural hospitals and clinics find reliable power in rooftop solar

Raichur (AP) — In the searing heat that often envelops Raichur, an ancient town in southern India, a ceiling fan that spins without interruption brings sweet relief for the newborn babies and their mothers at the Government Maternity Hospital.

But such respite wasn’t always guaranteed in a region where frequent power cuts to India’s overmatched electrical grid can last hours. It wasn’t until the hospital installed rooftop solar panels a year ago that it could depend on constant electricity that keeps the lights on, patients and staff comfortable and vaccines and medicines safely refrigerated.

The diesel generator that used to provide emergency backup — spewing planet-warming gases and toxic smoke within breathing distance of newborns every time it was running — is gone. So is the need to use flashlights to see during one of the hospital’s roughly 600 births per year, as staff sometimes had to do amid a sudden blackout if the old generators weren’t working.

For Martha Jones, a senior nurse who has helped deliver countless babies, the reliability that solar has brought has been a revelation.

“We don’t even know when power is cut or when it has come back,” Jones said.

In semi-urban and rural regions of India and other developing countries with unreliable power grids, decentralized renewable energy — especially solar — is making all the difference in delivering modern health care. And it’s becoming even more indispensable where heat and weather extremes are increasing due to climate change. In Raichur, for example, temperatures can soar to 42 degrees Celsius (107 degrees Fahrenheit) in the warmest months.

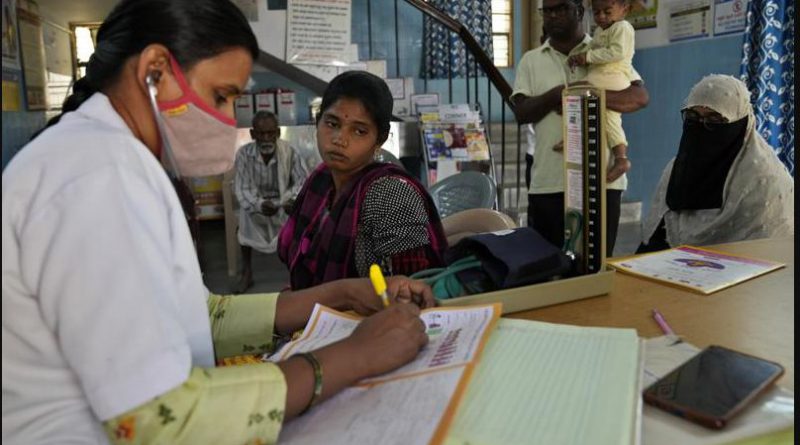

The hospital, Government Maternity, a bare-bones facility that serves thousands who can’t afford private health care, is one of 251 medical facilities in the Raichur district that runs on rooftop solar under a program spearheaded by Selco Foundation. The Bengaluru-based not-for-profit has raised funds from Indian and international corporations and coordinated with the local government since 2017.

It costs about $8,500 to install a system at public health care centers, including lead-acid batteries that store power for use at night. Smaller clinics run closer to about $2,000. The sites remain connected to the power grid, but only as a backup to the solar.

Some of Government Maternity’s patients, like 25-year-old Sandhya Shivappa, said they knew little or nothing about the hospital’s use of solar power and were simply grateful for its free services.

“We would be paying 30,000 rupees ($367) if I wanted to deliver my baby at a private hospital,” said Sandhya Shivappa, a 25-year-old who had just delivered a healthy baby girl when a reporter visited.

Shifting the hospitals and clinics to clean energy helps cut emissions in a sector that accounts for about 4.4% of the global figure, according to a study by Health Care Without Harm, an international nonprofit that advocates to reduce that. And that fits broader goals in India, the world’s most populous nation and the third-largest emitter of planet-warming gases.

While India currently relies heavily on coal for its electricity, it has a target of installing 450 gigawatts of renewable energy that should account for about half its needs by the end of this decade. Rapid increase in solar, especially rooftop solar, will be necessary to meet that goal.

India has currently only installed about one-fourth of the 40 gigawatts of rooftop solar that policymakers had planned to have by last year. Supply chain issues and taxes on imported components — intended to protect domestic makers — have contributed to that shortfall. But India has also constantly reiterated the importance of getting money from developed countries and multilateral development banks to help achieve its climate goals.

Besides providing uninterrupted power, the rooftop solar is helping the medical facilities cut costs. In nearby Zaheerabad, a low-income neighborhood, Dr. Kavyashree Sugur said the public health center she oversees has paid at least 50% less for electricity in the two years since installing solar panels.

That’s a big benefit in a country that is among the lowest spenders on health care in the world — India spends just a little more than 2% of its national budget on health care, compared to the United States’ 18% — and many hospitals and health clinics are cash-strapped.

The addition of solar to health care centers in remote regions has been especially important for villagers who don’t have the time or money to visit hospitals in the city, and likely would have simply gone without health care, said Hanumantappa Channadaser, Selco’s branch manager in Raichur.

“Before solar, people were apprehensive to visit these hospitals because of power shortages and they didn’t have faith in the treatment they might get,” Channadaser said.

Recently, Selco, the Ikea Foundation and the Indian health ministry announced that they will set up solar power for 25,000 government health care facilities across 12 Indian states by 2026. Ikea has committed $48 million to the project. Selco is also working with the International Renewable Energy Agency and World Health Organization in Africa to scale up decentralized solar for health facilities on that continent.

Shireen Fatima, who was four months pregnant and visiting the Zaheerabad health care center for a checkup, said she appreciates how “blood tests, tablets, everything is free here.” The hospital’s shift to solar energy is “definitely good,” she added.

“If the hospital is saving on bills, the benefits will be for us too,” she said.