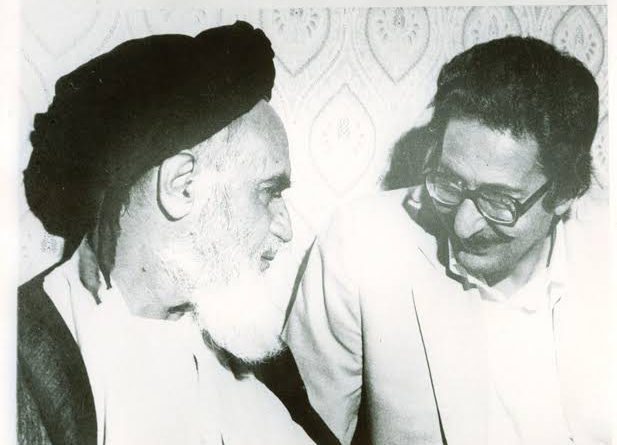

Former Iranian President Bani-Sadr dies in Paris

Paris (Reuters) – Abolhassan Bani-Sadr, who became Iran’s first president after the 1979 Islamic revolution before fleeing into exile in France, died on Saturday aged 88.

He died at the Pitie-Salpetriere hospital in Paris following a long illness, his wife and children said on Bani-Sadr’s official website.

Bani-Sadr had emerged from obscurity to become Iran’s first president in February 1980 with the help of the Islamic clergy. But after a power struggle with radical clerics he fled the following year to France, where he spent the rest of his life.

In announcing the death, his family said on his website that Bani-Sadr had “defended freedom in the face of new tyranny and oppression in the name of religion”.

The family would like him to be buried in Versailles, the Paris suburb where he lived during his exile, his longstanding assistant, Jamaledin Paknejad, told Reuters by telephone.

In an interview with Reuters in 2019, the former president said that Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini had betrayed the principles of the revolution after sweeping to power in 1979, adding this had left a “very bitter” taste among some of those who had returned with Khomeini to Tehran in triumph.

Bani-Sadr recalled in that interview how 40 years earlier in Paris, he had been convinced that the religious leader’s Islamic revolution would pave the way for democracy and human rights after the rule of the Shah.

“We were sure that a religious leader was committing himself and that all these principles would happen for the first time in our history,” he said in the interview.

Bani-Sadr took office in February 1980 after winning election the previous month with more than 75% of votes.

But under the new Islamic Republic’s constitution, Khomeini wielded the real power – a situation that has continued since Khomeini’s death in 1989 under Ayatollah Ali Khamenei.

Power Struggle

Within months of being elected, Bani-Sadr was locked in a power struggle with radical clerical factions whose powers he tried to curb by giving key jobs to liberal-minded laymen.

He used his election victory and popularity — thanks to his close links with Khomeini — to discredit his arch rivals in the Islamic Republican Party (IRP), a well-organised group led by hardline clergymen.

In his attempts to form a non-clerical cabinet, Bani-Sadr was also encouraged by a never-fulfilled pledge from Khomeini that the clergy should not assume top posts and instead devote their time to giving guidance and advice to the government.

While enjoying the support of moderate clergymen, he mounted a nationwide campaign against the IRP, travelling around the country and giving speeches in which he accused its leaders of trying to restore the dark days of the past through lies, trickery, prison and torture.

The power struggle reached a crucial point in March 1981, when Bani-Sadr ordered security forces to arrest religious hardliners trying to disrupt a speech he was giving at Tehran University.

This prompted calls for his dismissal and trial, as most of those at the rally were supporters of the opposition People’s Mujahedin, denounced by Khomeini as enemies of the revolution.

Khomeini, who had tried to stay out of the wrangling, then stepped into the increasingly bitter infighting, banning political speeches and setting up a commission to settle disputes.

The commission accused Bani-Sadr of violating the constitution and Khomeini’s orders by refusing to sign legislation.

Impeachment

With Khomeini’s consent, parliament impeached and dismissed Bani-Sadr in June 1981, forcing him to go underground with the help of the Mujahedin.

One month later, he flew to Paris, where he formed a loosely-knit alliance with the group to overthrow Khomeini.

The alliance collapsed in May 1984 in a clash of ideas between the then Mujahedin leader Massoud Rajavi and Bani-Sadr.

Despite disappointment and his long exile, Bani-Sadr said in the 2019 interview that he did not regret having been part of the revolution.

Bani-Sadr is survived by his wife Azra Hosseini, daughters Firouzeh and Zahra, and son Ali.