EXPLAINER: ISIS in Iraq—Weakened but Agile

by Raed Al-Hamid

ISIS relies purely on geographic terrain to plan and execute its activities…

ISIS has significantly increased its operations over the past year after a reorganization that saw it focus on creating mobile groups of fighters to conduct smaller-scale attacks. Understanding how its reconstituting itself as an insurgent force and at these early stages is critical to preventing its resurgence.

ISIS in Iraq’s urban areas appears to have reorganized its fighters in small “mobile” subgroups. The group has reformulated its fighting strategies in accordance with new realities on the ground: a decline in its ability to fight after losing first-tier leaders and thousands of fighters in its 2017 territorial defeat, U.S. sanctions on many of its financial resources, and its decreasing ability to recruit and sustain new blood. Nonetheless, ISIS is ramping up its activities in areas in which it still has influence by exploiting Iraq’s internal problems and utilizing familiar geographical territory.

Varying Estimates of ISIS Fighters

In August 2020, almost two years after the group’s military defeat, the U.N. estimated that more than 10,000 ISIS fighters were still operating in Iraq and Syria. This is similar to a late 2019 assessment from counter-terrorism authorities in the Kurdistan region of Iraq, which estimated 10,000 ISIS members in Iraq, 4,000-5,000 of whom were fighters and the rest of whom were supporters and sleeper cells integrated into local communities in the majority-Sunni provinces of western and northwestern Iraq.

These numbers far exceed estimates from Iraqi intelligence, which puts the number of ISIS fighters in Iraq at 2,000-3,000, including 500 fighters who infiltrated the country out of 859 fighters who escaped from the detention of the Syrian Democratic Forces in October 2019.

All these estimates may be more than the real numbers of ISIS combatants who launch attacks on selected targets, set up ambushes, plant explosive devices, kidnap and assassinate social and political leaders, and undertake other operations in keeping with the organization’s strategic priorities. ISIS has been able to revive these operations three years after its military defeat in its last stronghold in the Iraqi city of Rawa, 90 kilometers (56 miles) east of the city of Al-Qaim on the Syrian border, on Nov. 17, 2017.

A study of security operations against ISIS in Iraq shows that most do not result in the arrest or killing of large numbers of ISIS fighters. Military units from various branches of the security forces and the Popular Mobilization Forces Shia militia alliance, including tribal units, from multiple provinces participate in these operations, which are supported by the air forces of the Iraqi Army and the international coalition and cover large areas of more than one province. These include, for example, the “Lions of al-Jazeera” operation that was launched in May 2020 and encompassed the provinces of Anbar, Ninewa, and Salah al-Din. These operations often uncover tunnels, which are — in addition to caves — essential places, called madafat or “guest houses,” for harboring ISIS fighters, and finding explosive belts and IEDs.

The military operations to combat ISIS cells are disproportionate with the results. The officially announced outcome of the “Lions of al-Jazeera” campaign resulted in the arrest of two suspects, the destruction of two hideouts, the controlled detonation of four explosive devices, the deactivation of a booby-trapped house, the destruction of a tunnel, and the seizure of two motorcycles.

In Anbar Province, according to official results announced by the Defense Ministry’s Security Media Cell, the security forces participating in “Lions of al-Jazeera” announced on Oct. 1, 2020, that three ISIS fighters had been killed in one of the tunnels in which they found projectiles of various types in modest numbers.

In Salah al-Din province, after a series of operations to clear the Makhoul mountain range, the Security Media Cell announced in November 2020 that it had found five tunnels and some military equipment but did not arrest or kill any of the organization’s fighters.

The press briefings about these security operations do not indicate that a significant number of ISIS fighters were killed, nor do they indicate that clashes between security forces and ISIS fighters took place except in rare cases. They do reveal the destruction of shelters, weapons, and combat equipment that the organization had stored in desert and mountainous areas once ISIS realized that defeat was inevitable.

The security forces, including units of the Popular Mobilization Forces, attach great importance to decoupling Iraq from Syria such that it does not serve as a singular battlespace for ISIS by restricting the cross-border movement of fighters and weapons. In this way, they seek to prevent the infiltration of ISIS fighters from Syria into Iraq, as these fighters hide in the deserts of Anbar and Ninewa to prepare to move to areas that are important to the organization in terms of security, such as the Makhoul and Hamrin mountain ranges in Salah al-Din. At the same time, the Popular Mobilization Forces control the Syrian-Iraqi border to facilitate their own interests such as trade and weapons flow from and to Syria.

The security forces succeeded in securing more than 450 kilometers (280 miles) of the 610-kilometer (379-mile) Iraqi-Syrian border by cooperating with the International Coalition to install surveillance towers, barbed wire, and thermal cameras, in addition to reconnaissance drones.

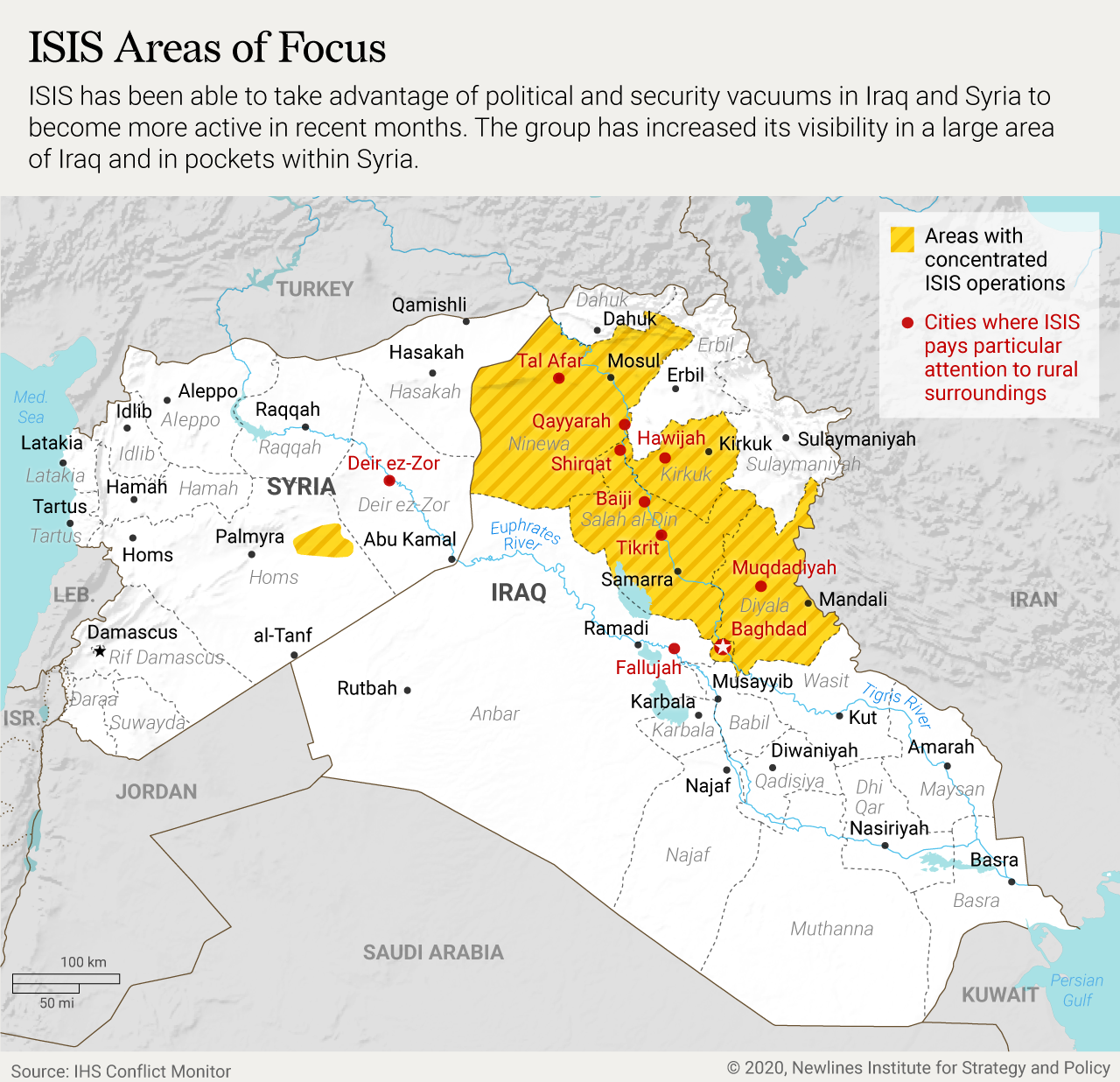

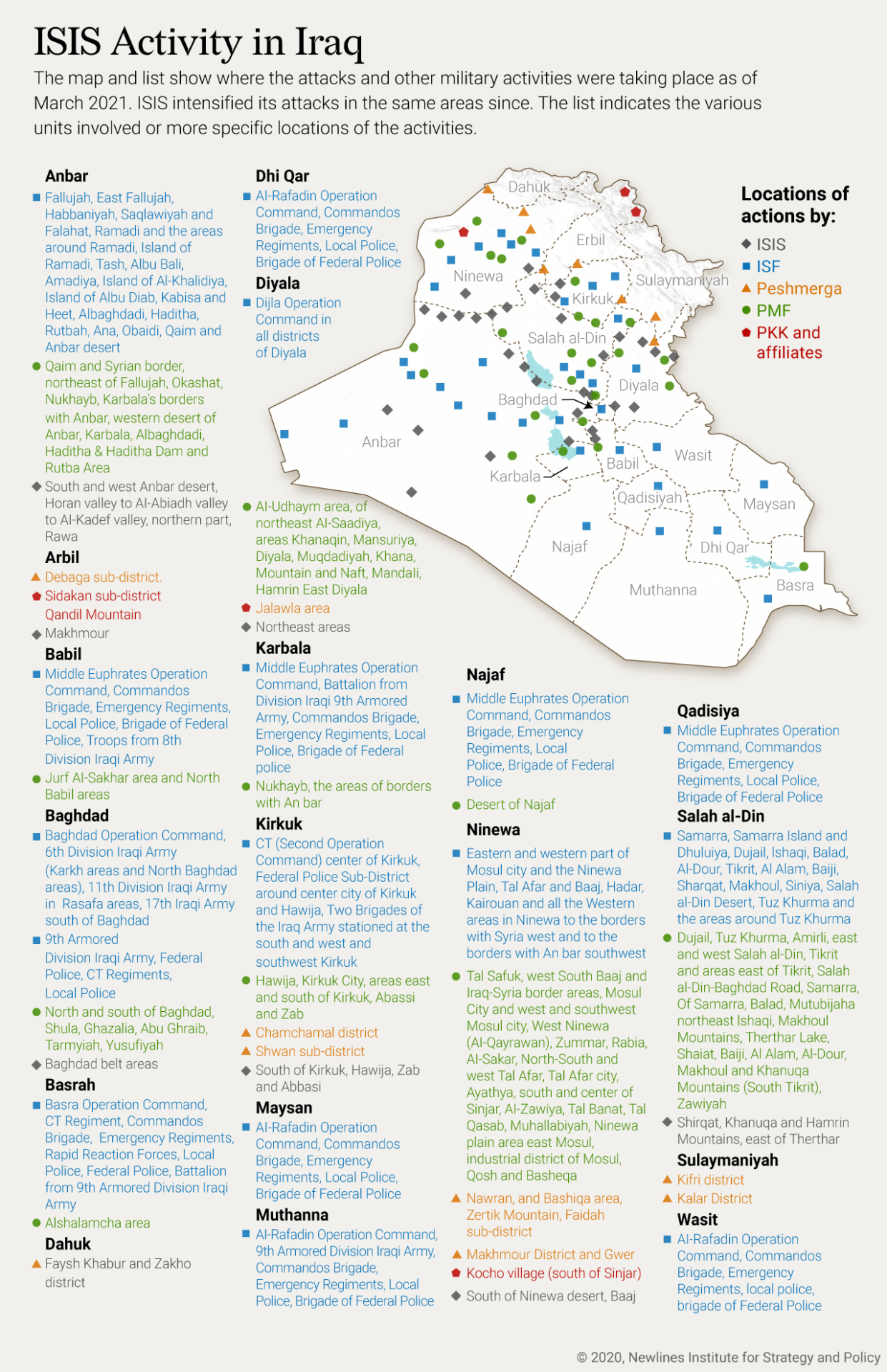

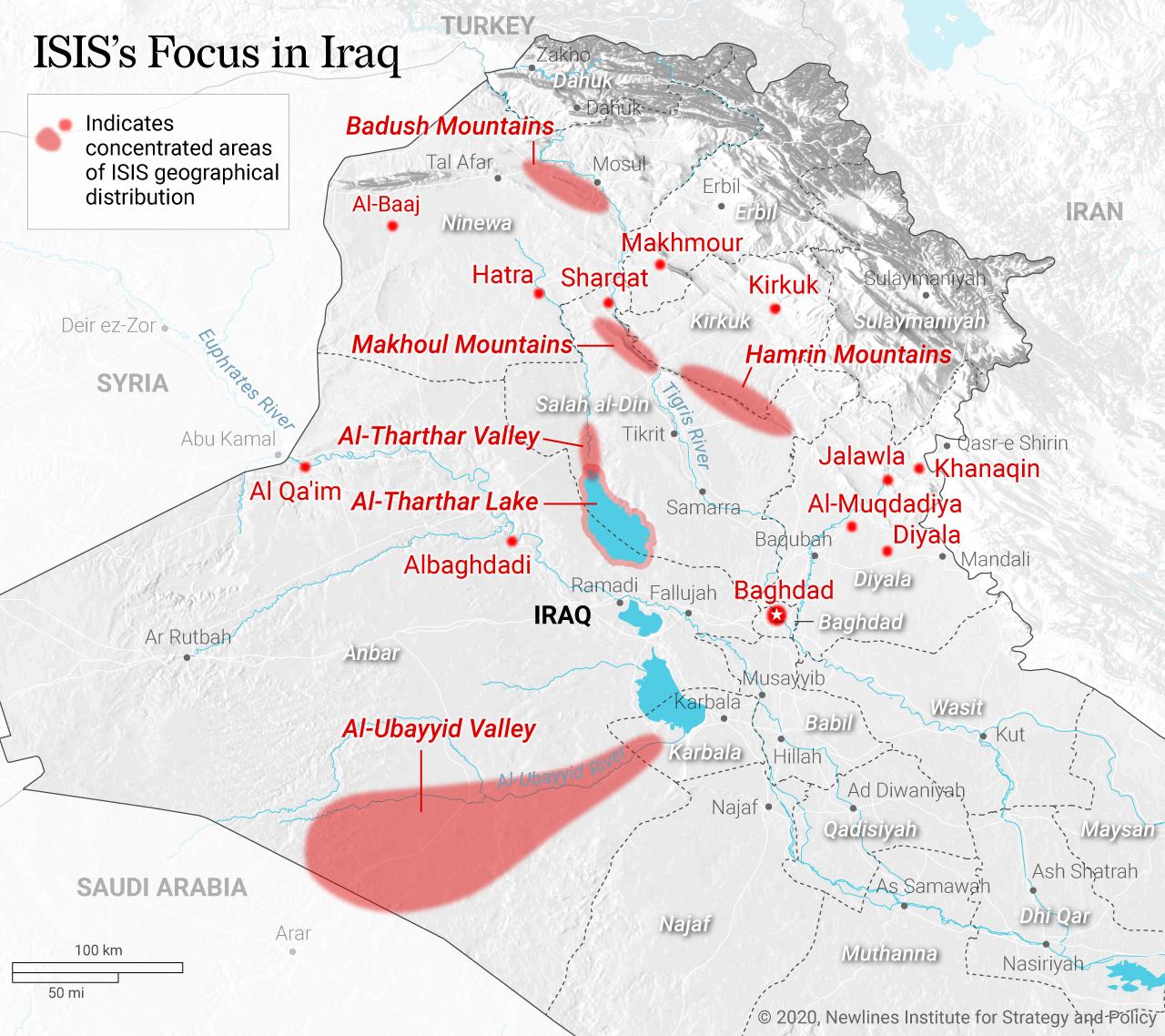

ISIS’s Geographic Distribution

ISIS’s increased use of “mobile groups” that carry out operations in different areas — often far from its bases or from shelters such as the madafat, which are located in rough terrains, rocky caves, or underground tunnels — means the group’s actual presence cannot be judged by its territorial claims or by announcements from Iraqi authorities.

No longer concerned about maintaining its wilayat (province) structure, and by ignoring the federal government’s administrative divisions, ISIS relies purely on geographic terrain to plan and execute its activities. Even though the group is no longer acting as a state as it was during the caliphate years from 2014 to 2018, its communiques claiming attacks still refer to the wilayat as part of its PR strategy.

Iraqi security officials’ statements indicate that the organization relies on remote bases deep in the desert in Anbar, Ninewa, mountain ranges, valleys, and orchards in Baghdad, Kirkuk, Salah al-Din, and Diyala to house its fighters and establish monitoring and control points to secure supply routes. It also uses these bases to establish command centers and small camps for training, digging tunnels, and exploiting caves in mountainous areas.

ISIS fighters’ geographical distribution can be inferred by examining the operations it launches against security forces and the Popular and Tribal Mobilization Forces. These fighters are distributed mainly in overlapping “geographical sectors” in Anbar, Baghdad, Babil, Kirkuk, Salah al-Din, Ninewa, and Diyala.

The first sector is an extension of the desert in eastern Syria. It constitutes a meeting point between ISIS fighters in Syria and Iraq, who move from there to Salah al-Din, which represents the main land communication node for the organization. It links ISIS groups coming mostly from Syria through Anbar and then moving to neighboring provinces: to the south reaching the northern belt of Baghdad, east to Diyala, north to Kirkuk, and to the northwest reaching Ninewa. This sector includes Anbar and Ninewa provinces within a wide desert area interspersed with valleys, mountain ranges, and bodies of water.

One of the most important valleys in this sector that ISIS uses to house its fighters is Houran Valley, which descends 350 kilometers (217 miles) from Saudi territory and enters Iraq, ending in the Euphrates near Albaghdadi. Another is the Wadi Al-Ubayyid Valley, which passes the Saudi border and Anbar Governorate in the border region of Arar, and ends in Razzaza Lake in Karbala Governorate, south of Baghdad.

This sector also includes the desert of Al-Baaj district, southwest of Mosul and 50 kilometers (31 miles) east of the Syrian border, and the desert of Hatra district, south of Mosul. These two areas overlap geographically with the Anbar desert in the Al-Qaim region north of the Euphrates River and include the Badush mountain range, as well as the Al-Tharthar Valley and Al-Tharthar Lake, northeast of Anbar, next to Salah Al-Din province.

The second geographical sector includes areas overlapping with the first geographical sector in the southeast of Ninewa and northwest of Salah al-Din. It includes the geographical areas between the districts of Sharqat in Salah al-Din next to the Kirkuk and Makhmur in the southeast of Ninewa near Kirkuk and Erbil, the capital of the Kurdistan region.

The third geographical sector is the most important for the organization and the center of ISIS’s main activities. It includes Salah al-Din, Kirkuk, and Diyala provinces, extending to the Al Kateon sector and the areas of Al-Muqdadiya, Khanaqin, Jalawla, and Qarataba.

The sector features valleys such as Zghitoun and Shay in Kirkuk, agricultural areas with dense orchards suitable for hiding and transporting ISIS fighters, setting up ambushes, and planting explosive devices. ISIS mobile groups in this sector in Salah al-Din overlap groups in Diyala through the Makhoul and Hamrin mountain ranges.

In addition to the three main geographical sectors, ISIS groups have a presence in the western Baghdad belt areas in Abu Ghraib and Radwaniyah and in the northern Baghdad belt in Rashidiya, Tarmiyah, and Al-Mashahidah. They also exist in the cities of Balad and Samarra, in the south of Salah al-Din, and south of Baghdad in the Jurf al-Sakhar area, located 50 kilometers to the east of Amiriyat al-Fallujah in Anbar.

ISIS cells are also present in areas that are in dispute between the Iraqi central and Kurdistan regional governments, where the lack of security coordination gives the organization some freedom of movement. This was especially true after the Kurdish peshmerga forces evacuated these areas in October 2017 following then-Prime Minister Haydar al-Abadi’s decision to move Iraqi security forces and Popular Mobilization Forces to control these areas after a September 2017 independence referendum organized by the Kurds.

Other areas, however, have witnessed joint operations by security forces from several governorates to track down and hunt ISIS fighters and destroy their bases. The first phase of the operation “The Lions of Al-Jazeera II” operation, which was launched on Feb. 1, 2020, with the participation of units from the Al-Jazeera Operations Command, the West Ninewa Operations Command, the Salah al-Din Operations Command, and Popular Mobilization Forces brigades (including tribal units) is a key example of this kind of coordination.

ISIS’s Operations on the Rise

According to information I have obtained through monitoring official Iraqi and non-Iraqi sites and other sites close to ISIS, the organization has carried out dozens of operations in Iraq since the start of 2021. The propaganda ISIS has employed often takes advantage of highly publicized global events to carry out attacks and show the world they are still present. The election of U.S. President Joe Biden was such an event, and ISIS escalated the pace of its attacks after Biden’s inauguration.

According to media outlets close to ISIS, such as Amaq News Agency, the group carried out 1,422 operations in 2020, an average of four per day. The organization’s main tool was explosive devices, used 485 times, followed by 334 sniping operations, in addition to 252 clashes or exchanges of fire. Another 94 execution operations were carried out against individuals affiliated with security services, the Popular Mobilization Forces, or the Kurdish peshmerga forces and against people cooperating with the government, including mayors and tribal leaders. There were an additional 257 operations that ISIS’s media outlets mention but do not classify.

Amaq claims the organization killed or injured 2,748 people in 2020, including 724 killings in Diyala, 643 in Salah al-Din, 576 in Anbar, 474 in Kirkuk, 210 in Baghdad, 104 in Babil, and 26 in Ninewa. This indicates a 50% increase in operations compared to 2019 and 11% more deaths and injuries.

The group also claimed to have destroyed or damaged 559 vehicles of various types, 85 houses and farms, 60 thermal cameras, 34 barracks, and 28 electrical energy transmission towers, most of which were in Diyala, Babil and Anbar.

ISIS was limited to operations that do not require large numbers of fighters, including planting IEDs, setting up ambushes, sniping operations, assassinations, and burning homes and farms, none of which have major political or security repercussions. An exception is some limited “special operations,” such as the one in which two suicide bombers detonated in Tayaran Square in central Baghdad on Jan. 21, killing more than 30 people and wounding dozens in a “rare” security breach, nearly three years after the last operation in the capital that was claimed by the organization.

Pandemic, Security Vacuum Provided Openings

ISIS took advantage of the security vacuum in early 2020 after the outbreak of the coronavirus pandemic and the tensions between the U.S. and Iran. Two days after the Jan. 2 assassination of Iranian Maj. Gen. Qassem Soleimani and Popular Mobilization Forces deputy commander Abu Mahdi al-Muhandis, coalition forces, wary of escalation, announced a brief halt in training Iraqi forces. The training resumed but was halted again on March 19 due to the spread of COVID-19 in Iraq. Coalition forces repositioned to different camps, and some countries such as the United Kingdom and Spain withdrew soldiers from Iraq.

Soleimani’s assassination also prompted the Iraqi parliament to vote in January 2020 for the withdrawal of foreign forces. Official figures stated that before the pandemic there were about 8,000 foreign troops in Iraq, including 5,200 from the United States, while unofficial sources say the real number exceeds 16,000. The United States reduced the number of its soldiers in Iraq in September 2020 to about 2,500 soldiers in response to the Iraqi government’s request.

This vacuum gave ISIS more freedom of movement for its mobile groups, facilitating logistical support and the restructuring and distributing these groups in a way that allowed the organization to securely cover the areas where its fighters are deployed. These deployments were in areas far from Iraqi security forces, which did not announce any military operations until April 2020. The first operation included the governorates of Diyala, Anbar, and Salah al-Din and was undertaken in response to the killing of 170 civilians and soldiers, along with 135 militants during the first quarter of 2020.

Weakened but Still Effective

Via its mobile groups, ISIS still possesses sufficient combat capabilities to threaten security and stability, but the group remains very weak. Currently, the organization still lacks the ability to execute major operations, and its attacks are limited to open targets that are not of strategic importance. What this means is that it is unlikely to attempt to take control of territory in Iraq or Syria due to the decline in its combat capabilities and financial resources. The group also remains vulnerable to the international coalition and Iraqi security forces if it tries to accelerate the pace of its resurgence.

ISIS needs to recruit new fighters and rebuild its leadership system to centralize control, whether in directing orders or gathering security and intelligence information to prepare for major operations. Recruiting is more difficult, especially after its four years of control over territory led to widespread societal rejection of its authority. Local communities have been more closely cooperating with coalition and security forces to prevent ISIS from making a comeback, especially after witnessing increased stability in areas where tribes cooperated with the authorities. That said, the organization still attracts some unemployed people, outlaws, or people hunted down for social reasons, all of whom find that joining the ranks of the organization is a means of escaping from social and judicial prosecutions, in addition to ensuring minimum means of subsistence.

This decline in local support also gives ISIS less flexibility in attracting funding. After gaining control of Mosul in 2014, ISIS relied on diversifying its sources of financing, whether by controlling hundreds of millions of dollars (for example, more than $420 million from state banks in Mosul) or by producing and marketing oil from fields it controlled in Iraq and Syria. It also trades in hard currencies through exchange and transfer networks, using third parties such as the Al-Ard Al-Jadidah company that moved from its headquarters in the city of Al-Qaim to the Turkish city of Samsun after the defeat of ISIS in Iraq. The company is part of the Al-Rawi Network that was run by Fawaz Muhammad Jubayr al-Rawi in the Syrian city of Albu Kamal, before he was killed in a June 2017 airstrike.

In December 2016, the U.S. Treasury Department included Fawaz Muhammad Jubayr al-Rawi and other members of the Al-Rawi Network and associated entities such as the Al-Ard Al-Jadidah company on the sanctions list for providing important financial and logistical support to ISIS.

Most of the organization’s activities during January and February of this year were concentrated in the Iraqi governorates of Baghdad, Diyala, Kirkuk, Anbar, Ninewa and Salah al-Din. ISIS took advantage of some security gaps resulting from the decline in the level of coordination between the active forces, whether the security forces, the Popular Mobilization Forces or the Kurdish peshmerga forces.

Ending ISIS is More than Combatting Terrorism

During more than four years of the war against ISIS, and in addition to the dozens of security operations announced by the Iraqi forces to hunt down the remaining ISIS fighters, the U.S.-led international coalition carried out more than 34,000 air and artillery strikes that contributed to a large extent in taking control of all ISIS-controlled areas in Syria and Iraq by March 2019. Yet, according to U.S. intelligence sources, , the organization was not defeated and remains a threat to the security and stability of Iraq and Syria, with evident activity in more than six provinces in western and northwestern Iraq.

The organization focuses its operations on targeting influential figures, especially those cooperating with the government and security agencies, to remove the obstacles it believes prevent it from recruiting more young people into its ranks and to limit the security cooperation that leads to the exposure of the organization’s members and fighters’ hideouts. It also aims to secure a “friendly” environment for the activities of its members in the Sunni community.

Ending the threat ISIS poses cannot be realized without a political settlement that reintegrates Sunni Arabs in the political process, a fair distribution of power and wealth according to the population proportions of Sunni Arabs, and rebuilding cities destroyed by the war on ISIS that lasted from 2014 to 2018. In addition, emigrants and forcibly displaced people should be allowed to return to the governorates in the west and northwestern Iraq, and the Popular Mobilization Forces’ control of most of these areas must end.

Additionally, efforts by the government and civil society organizations are needed to accept the social impact of the return of ISIS members’ families who are still in the camps and who are taught an ideology that adopts the ideas and approach of the organization. This is especially evident in the Al Hol camp in Hasakah, Syria, which includes thousands of ISIS families and members.

Article first published on New Line Institute For Strategy And Policy based in Washington D.C.

Raed Al-Hamid is an independent Iraqi researcher and former consultant for the International Crisis Group. He tweets under @Raedalhamid1.