OPINION: How ‘America first’ has mostly failed the US

by Andrew Hammond

Nevertheless, much of US policy has been characterized by incoherence and failure.

As Donald Trump enters his final month in office, it is increasingly clear that his much-hyped “America first” foreign policy revolution has largely failed.

When he entered the White House four years ago, Trump promised a platform of policies that could have reshaped US foreign and trade policy more radically than at any point since the beginning of the Cold War, when Harry Truman helped build a multidecade, bipartisan consensus around US global leadership.

To be fair, Trump has made some moves to deviate from this postwar orthodoxy by withdrawing from initiatives such as the Paris climate deal and the Trans-Pacific Partnership trade agreement, but what was billed as a transformative shift has proved threadbare and incoherent in practice, despite much bluster.

Seeking to dismantle previous policies, which could all be reversed again by Joe Biden in the next four years, is one thing. But building sturdy foundations of a new order, as Truman put in place, is quite another. This is why Trump has failed to forge any clear or coherent doctrine centered on “America first,” despite the political support this agenda enjoys in much of the US from those skeptical about US engagement overseas.

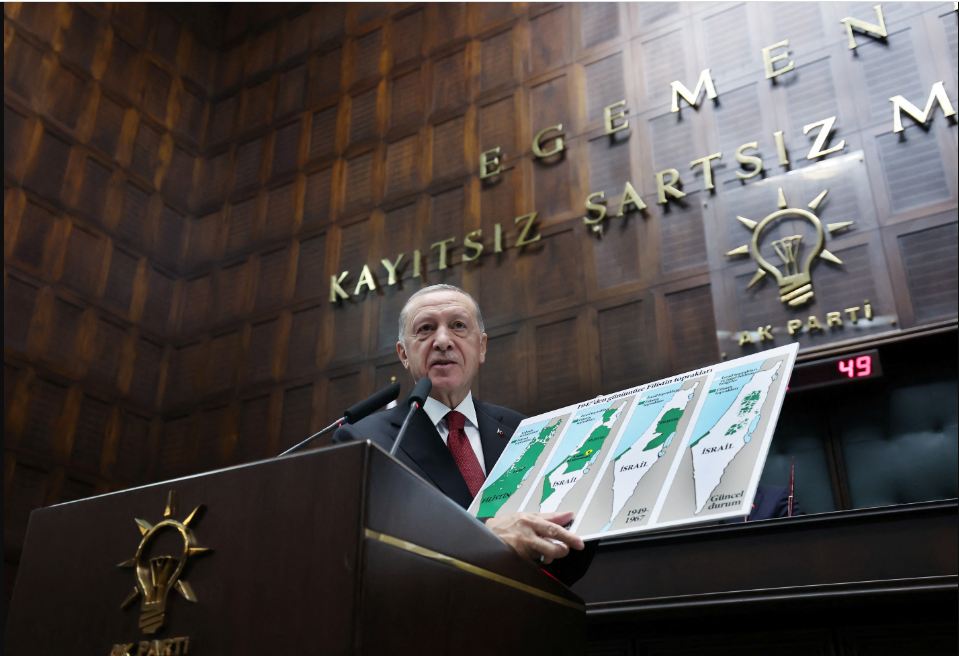

This is not to say that Trump has had no foreign policy achievements. He has, for instance, brokered Middle East peace agreements between Israel and Bahrain, the UAE, Sudan and Morocco that have been welcomed by many.

Nevertheless, much of US policy has been characterized by incoherence and failure. On issue after issue Trump has flip flopped and U-turned, including his stance toward NATO, which in his words has been both “obsolete” and “not obsolete.”

Another example is Trump’s renegotiation of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), a process he has celebrated as a “wonderful” and “historical transaction” when a revised deal was announced last year. However, the concessions he won were not nearly as big as he claimed possible after calling NAFTA the “worst trade deal ever,” underlining why he decided for public relations reasons to give the pact a new name to the United States-Mexico-Canada deal to try to disguise the significant continuities from before.

Moreover, he has also failed to push through signature initiatives in North Korea where he attempted to preside over “denuclearization” of the Korean peninsula and seal a peace treaty between North and South to supplement the armistice ending the 1950-53 Korean War. Another example is Russia, where Trump’s instincts to redefine relations in a significantly warmer direction alarmed even allies in his administration, and was set back by tightened US sanctions legislation.

These failures, sleights of hand, and flip-flops reflect not just the ad-hoc nature of the president’s style of governing, but also the divisions within his team on key foreign issues. While Trump appears to be much more aligned with US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo than predecessor Rex Tillerson, the divisions within his top team have gone much deeper than the State Department.

Trump’s relationship with key intelligence officials, including Dan Coats, who was CIA director from 2017 to last year, was extraordinary and unprecedented. The president has been at odds with the intelligence community on issues from North Korea to Iran and Daesh.

Another example is Trump’s announcement a year ago that US military personnel in Syria were “all coming back and they are coming back now.” This proclamation, which appeared not to have been shared in advance with allies, was a contributory factor in the resignation of defense secretary Jim Mattis and, later, national security adviser John Bolton.

The one unquestioned accomplishment of Trump’s foreign policy has been to provoke significant global backlash as underlined from polls by organizations such as Pew and Gallup. Both have found that the image of US leadership is significantly weaker worldwide, and in some cases at historic lows. Among the key drivers of this is widespread resentment with the way the Trump team has been perceived to make its decisions, which often appear unilateral, leading to a sustained, deep spike in anti-US sentiment that may be only partially reversed under Biden’s presidency.

With his presidency now almost over, Trump’s window of opportunity to put an enduring stamp on foreign policy is slim. While he has done much damage, the one saving grace is that no first-order foreign crisis, especially an armed conflict involving the US, has taken place on his watch, for which his ill preparedness and maverick instincts could have been immensely dangerous.

Article first appeared on Arab News.

Andrew Hammond is an Associate at LSE IDEAS at the London School of Economics.