First Karsevak to hit the Babri dome becomes Muslim, promises to built 100 Mosques as repentance

By Murali Kirshna Menon

Mohammad Amir, physically nondescript, with a triple Masters in History, Political Science, and English, and an itinerant pilgrim, should know what he is talking about: Long ago, 25 years to be precise, he had a dalliance with insanity.

We are sitting, deep into the night, in the well-carpeted office of one of Amir’s well-wishers in Malegaon. Among those ringed around him are a mechanic, a fruit-vendor, some traders and the loquacious principal of a junior college in Malegaon with a penchant for the dramatic and for hijacking the conversation.

Earlier that evening, Amir had addressed a gathering at a Masjid in Madhavpura. “Woh toh zameen ke neeche ki, aur aasman ke upar ki baate karte hain,” says one of his admiring audience.

Meditations on the afterlife — and on the ethics of Islam and social conduct of Muslims — might dominate his talks, but Mohammed Amir is often at the pulpit because of the torturous chrysalis he has emerged from, he now says.

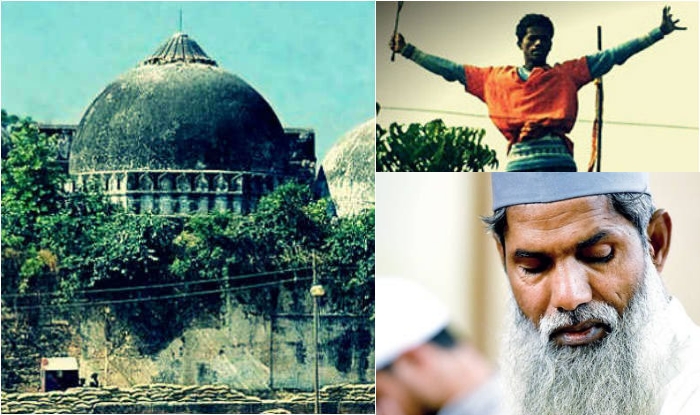

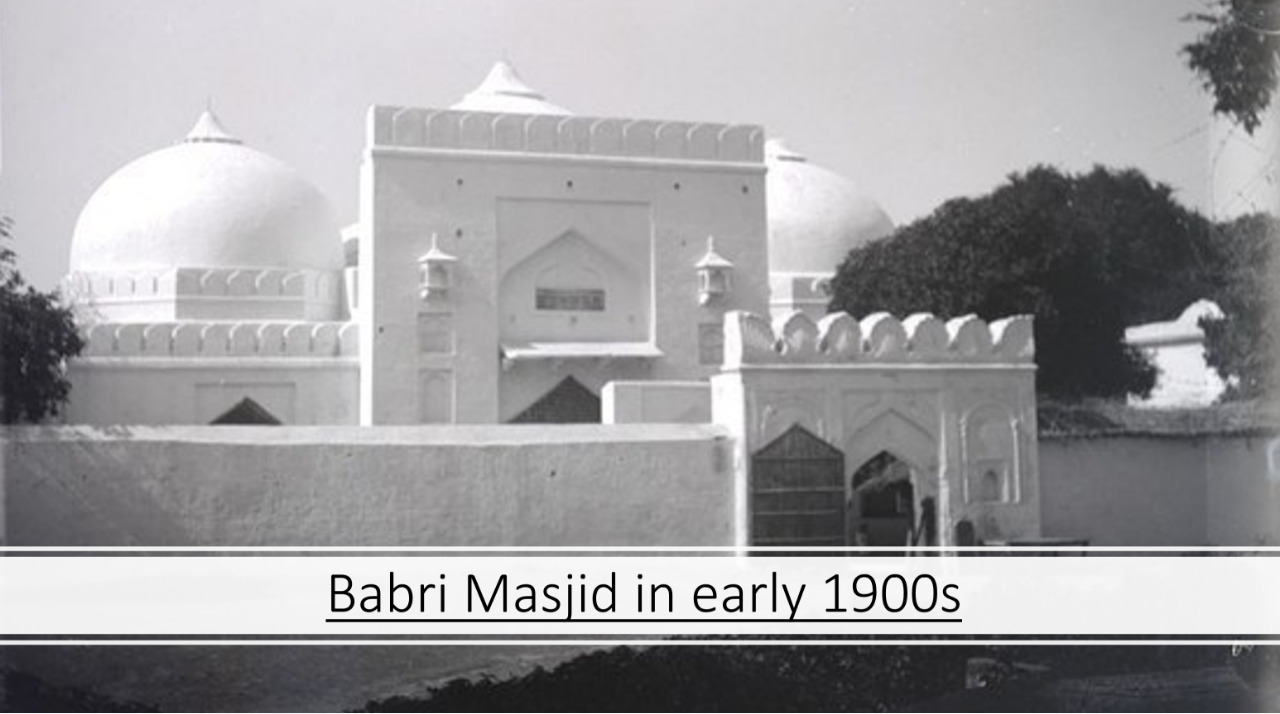

Twenty-five years ago he was not Mohammad Amir but a certain Balbir Singh, and the highlight of his life until then was that he was among the handful of kar sevaks who had clambered up the dome of Babri masjid to strike the first blows. The same kar sevaks who were lionised by Bal Thackeray as his men.

“I am a Rajput. I was born in a little village close to Panipat,” he discloses. “My father, Daulatram, was a school teacher and a man of deep Gandhian leaning. He had witnessed the horrors of Partition, and went out of his way to make the Muslims in our area feel secure. He had wanted me and my three elder brothers to do the same.”

When he was ten, Balbir’s family moved from the village to Panipat so that the children could complete their secondary education. Panipat, he says, was a hostile city, especially to children from rural Haryana. Barbs were made about their clothes and gaucheness, and none of the other children played with them. The only place Balbir found he was not discriminated against was at the local RSS shakha. “I remember the first time I was there, they addressed me as ‘aap’. That made me feel so good. It marked the beginning of my association with them.”

About a decade or so later, Balbir, who had by then joined the Shiv Sena, started working with his brother in the family’s loom business and got married. He continued his studies on the side, garnering the triple MA degrees from Rohtak’s Maharishi University. To all appearances, it was the life of normal middle class householder. But a rank bitterness, unseen to the outside eye, ran through the family because of his political views. In that Gandhian household, he was the ‘chaddiwallah.’

The truth of the family lay somewhere in between. “People thought I was a hard-core Hindu fanatic, but that was not really the case. As my father never believed in idol worship, we didn’t go to temples,” he says. There was a copy of the Gita at home but he rarely, if ever, read it. His anger at the beginning of the tragically momentous Nineties was against historical wrongs, against Babur, Aurangzeb and the other conquerors.

“Brainwashing me was easy, because yeh bhavnayen (these emotions), they are deep-rooted. Back where I come from, if you did something that was not considered acceptable, even a simple thing like eating a roti with your left hand, people would ask, “Tu Mussalman hai ke?” (What is this? Are you a Muslim?) I thought that these Muslims came from outside India and had snatched our land and destroyed our temples.”

Plus, in a state like Haryana that valorises machismo, he said he wanted to do something that would effectively show his ‘mardangi.’ “When I left for Ayodhya in the first week of December, my friends told me, ‘kuch kare bina wapas na aana (Don’t come back without achieving something)’,” says Balbir who was among those being tracked by the Intelligence Bureau.

“Ayodhya was abuzz on December 5,” he recalls. “The men from VHP ruled the town and Faizabad. We stayed with thousands of other kar sevaks, heard the chatter going around. Advaniji was not important because he worshipped Jhulelal (the community god of Sindhis), and hence was not considered to be a Hindu; Uma Bharati was a drama queen. I was there with my close friend Yogender Pal. We were all impatient, we wanted to get going.”

A few distinct shards of the following day are still embedded painfully in his memory of it. One of them is an aural one, of the rousing slogans (‘Saugandh ram ki khai hai, mandir yahin banayenge’; ‘Kalyan Singh kalyan karo, mandir ka nirmaan karo’); he remembers mocking senior police officials as he walked along with the other kar sevaks towards Babri Masjid on that cold afternoon; and then the final rush and the frenzied scramble atop the central dome.

“I was like an animal that day. Only briefly, I got scared when I saw a helicopter approach us from a distance. Then, the rallying cries from below reached my ears and I felt emboldened again and plunged my pick-axe into the dome.”

A heroes’ welcome awaited Balbir and his friend Yogendra Pal when they returned to Panipat. Two bricks that they brought back from the rubble in Ayodhya were kept at the local Shiv Sena office, he says. At home, though, his father issued an ultimatum. “It was either him or me. One of us had to leave the house, and I decided that it would be me. I looked at my wife but she just stood there, so I left home alone.” As riots erupted across the country, Amir sought places of refuge where “Muslims wouldn’t be able to get him.” He remembers solitary wintry nights spent in fields, decrepit old buildings, drains.

He was on the run for a couple of months and only returned home when he learnt that his father had passed away. But his other family members no longer wanted him. His father had specifically instructed that his second-born son shouldn’t be allowed to attend his funeral. “They said I was the reason for his death.”

But an even bigger shock awaited Balbir. His close friend and collaborator at Ayodhya, Yogendra Pal, had become a Muslim. The aftermath of the December 6 frenzy and the riots had left Pal deranged. When Balbir went to meet him, Pal told him that embracing Islam had helped soothe his mad thoughts and fears. “While talking to him, it occurred to me, would I too go mad because of the sin I had committed and what I had helped unleash? In fact, was I already going mad?”

It was at Pal’s instance that in the June of 1993, six months after the climax at Ayodhya, Balbir travelled to Sonepat to meet Maulana Siddiqui who had converted his friend Yogendra Pal.

Siddiqui heads the Imam Waliullah Trust for Da’wah, which is based in Phulat, near Muzzafarnagar, and runs several madrasas and schools across north India. Siddiqui was in Sonepat for an event, and Amir went up to him and told him what he had done. He asked the maulana if he could come and stay at the madrasa in Phulat for some time. “I was still not sure if I wanted to convert, but he accepted my request. He told me that I had contributed to the destruction of one mosque, but I could always help build several others. They were such simple words. I sat down and began to cry.” After spending a few months at the madrasa, Balbir converted and was given the name Mohammed Amir.

“Aur meri zindagi phir se chal padi (my life got back on the rails again),” he says simply.

While at Phulat, Amir learnt Arabic and read the Quran, and, since he had majored in English, he taught at the madrasa. In August 1993, he reconciled with his family, and his wife joined him at the madrasa the same year. She converted to Islam soon after (Amir claims that she did it of her own accord). Their four children were all born in Phulat.

After his wife left, though, his health began to fail and he was advised to move to the more salubrious south, which he did before going on to remarry, a widowed woman called Shahnaz Begum. But Amir, whose family sends him a monthly stipend, still often travels to Panipat to meet with them and his friends.

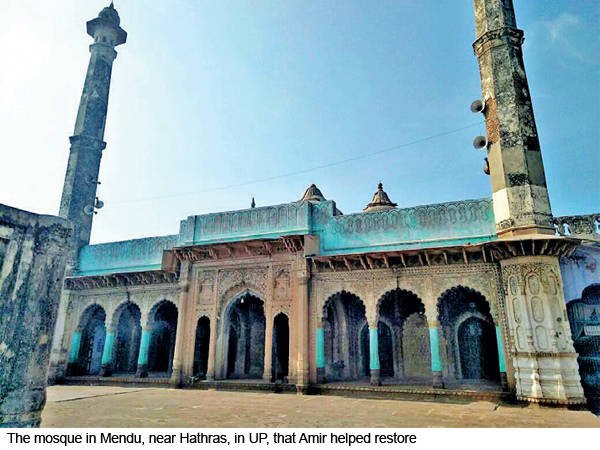

Between 1993 and 2017, he claims to have identified and restored several decrepit mosques in north India, especially in Mewat, with the help of the Waliullah Trust. Forty so far, he says, adding that he is especially proud of the work that he has done at a mosque in Mendu, near Hathras, Uttar Pradesh.

“There are several mosques in various stages of disrepair across north India that even the Waqf Board is not aware of. I seek out such places, clear them of encroachments, tidy them up and get people to start worshipping there again. At some places, I also set up madrasas, and that is especially important for me, since I believe the bane of the Muslim community is their total disregard for education.” Sometimes, he says, he is helped by Muslims in and around the area; at others, he does it alone. His goal is to repair and rebuild 100 mosques. That would get him something close to atonement.

People associated with the Imam Waliullah Trust, describe Amir as a quiet, committed man. “I met him in the early 2000s, and I would call him a gentleman and a social worker. He renovated the mosque near Hathras, which was abandoned after Partition. Some sixty students are now taught at the madrasa in Mendu,” says Zia-ul-Islam, a former section officer at the Aligarh Muslim University.

Presently, he says to the gathering at Malegaon, “When my health allows me and when I am not busy restoring decrepit mosques, this, talking to members of my community, is what I do. I always travel on my own money and return home as soon as my commitments are through.”

What does he talk to them about?

“Look at me, sir, I’m a ghissa-pita aadmi (a man who is worn out). What can I preach about but aman (peace)? That is what Islam has given me, and that is what I want to talk about. I tell my people that I was once a Hindu filled with hatred towards Muslims and ignorant about them, but people like me were, and are, in a minority.”

He advises them on the importance of not getting provoked. “I fear the worst, but I also tell them that Muslims are strong, too, and that while they can retaliate, a better way to engage with your oppressor is to forgive. It is a difficult thing to do when you consider yourself strong, but it sends out such a powerful message.”

Would it be accurate to describe his last 25 years as a quest to forgive himself?

“That would be one way to look at it, for letting down my father, for contributing to the deaths of so many people. But I also know that it’s a work in progress.”

The toughest kind of forgiveness is self-forgiveness and the road that leads to it is a lonely one, but it is also where mad meets the divine.

[First published by MumbaiMirror]