OPINION: Yunus Defies UN, Bans Bangladesh’s Awami League Without Referendum

Bangladeshi democracy has always been a bit of a balancing act—it’s fragile, often disputed, and shaped by deep mistrust among the parties involved.

Yunus stepped in like a hero after Sheikh Hasina’s narrow safe exit. Seriously, why Yunus though? Sure, that Nobel Prize glow—“banker to the poor,” all very inspirational. But running a whole country? That’s a bit out of his usual comfort zone, isn’t it? Critics aren’t buying his résumé for democracy. He’s got a squeaky-clean political record, yeah, but there’s the tiny problem of zero political success, too.

Did any of that bother the crowd of fired-up July protesters celebrating him? Or the business bigwigs who just wanted things to stabilize for a minute? Doubt it. People were desperate for any kind of shake-up. Someone new. Yunus just fit through the vibe—calm, politically unknown, totally untested on the big stage. Yunus on many occasions on International and National Media, claimed he or his cabinet has no plans to ban Awami League. He has gone to the extent that it is up to Awami League if they want to participate or not, yet Awami League activities were repressively banned without any referendum.

Islamists, NCP stage ‘Mist Spray’ protest in Summer to ban Awami league?

Awami League-oldest, secular, the party that led Bangladesh to freedom. But now, its legacy is questioned. Sheikh Hasina, the longest serving female Prime Minister, once stood in parliament and called Yunus the “Blood Sucker of the poor”. Now, the tables have turned. The UN’s fact-finding report blamed Hasina, her party, and security forces for the deaths of at least 1,400 people during the 2024 protests-children among the victims, crimes against humanity, said the report. Awami League pushed back: the report lacked their side, relied on unnamed witnesses and many more accusations. But who listens to the Awami League now? The UN’s word carries more weight, its credibility unshaken in the global court of opinion.

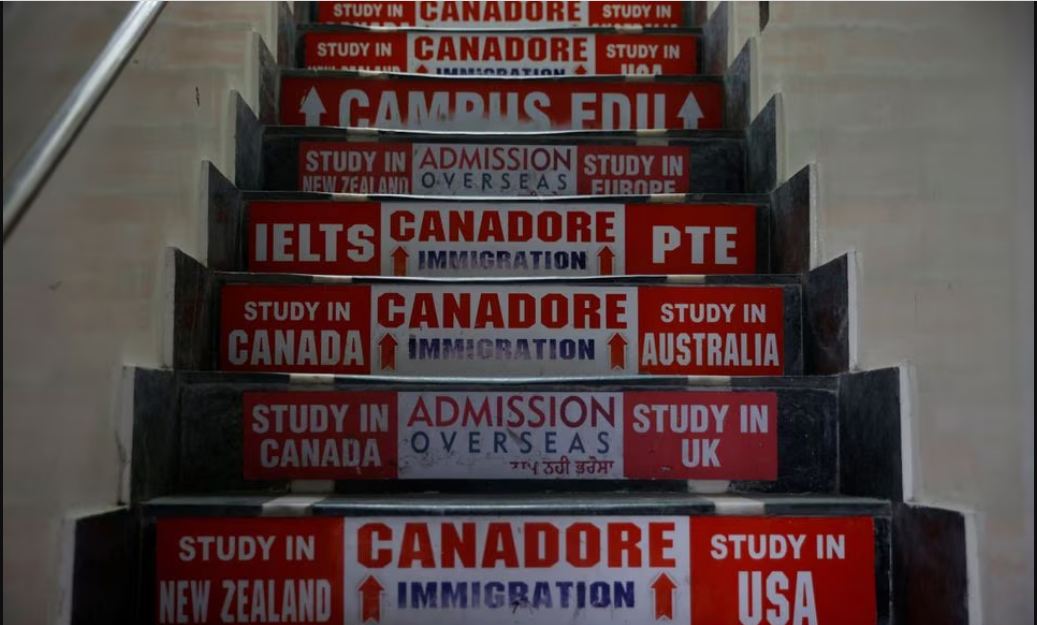

Protests went on for days, with people demanding that the Awami League be banned. The crowd was a bit of a weird mix — Islamists like Mufti Jasimuddin Rahmani, Asif Adnan, Hizbut Tahrir, Jamaat-e-Islami, and Hefazot-e-Islam all shouting for the party to be shut down. Some wondered if this was a real uprising or just a show put on by the government. Some said the ultimatum to Yunus wasn’t genuine, just a way to make the ban look legit.

Yet, Yunus, now acting as the caretaker, ordered a gentle mist spray at the summer camps — basically keeping the protesters hydrated, not firing bullets. Did that cool things down or just buy some time? The protesters weren’t all in agreement about singing the National Anthem. Some felt uncomfortable with singing it because it was written by Rabindranath Tagore, many referred to him as Hindu despite him being from the Brahma Samaj. The protest interestingly wasn’t joined by BNP, other centrist, leftist parties but the newly formed student party NCP looked like they were a cover to the Islamists.

Is Banning Awami league a legitimate move?

Some argue that banning the Awami League because, as the ruling party, it ordered killings and human rights abuses—many of its members carried out these acts—seems understandable on some level. However, doing so amounts to punishing the party collectively, which is problematic. International human rights laws and criminal justice principles emphasize that responsibility should be based on individual actions, not on group membership. Punishing the entire party ignores this important rule and can lead to more harm. History shows that punishing groups doesn’t stop violence; instead, it often fuels cycles of revenge, pushes authoritarian measures, and weakens efforts for real justice and reconciliation in transitioning societies.

Comparing Bangladesh’s current situation to transitional justice processes in places like South Africa after apartheid, Liberia following its conflict, or Bosnia is not quite accurate. Those scenarios involved extreme events like genocide, ethnic cleansing, or civil war. While Bangladesh faces serious challenges, it doesn’t meet the legal criteria for mass atrocities to that extent that would justify drastic measures like dissolving political parties. Even in those extreme cases, restrictions on political participation were used sparingly, temporarily, and often with international oversight or as part of negotiated agreements. So far, Bangladesh hasn’t experienced the kind of broad consensus or legal process needed to meet that high threshold. Also, frameworks like South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission were designed specifically for their contexts and weren’t meant to be general models for banning political parties in countries trying to rebuild democracy after authoritarian rule.

The UN Fact Finding report also simply mentions that elements connected to the party actively supported the repression. This makes you wonder: how much was the party involved in the violence? Recommendation 370 of the Office of the UN High Commissioner of Human Rights, Fact Finding report into the Bangladesh July/August killings state to refrain from banning political parties that would undermine genuine return to a multi-party democracy. Although, the report doesn’t qualify as a legal verdict, yet the report was unjustly cited by the interim to oppress, torture, imprison and attack on Awami League activities. The attacks happened with both law enforcement and mobs, sometimes through a mixture of both. After the forced resignation of Chief Justice through forced anarchy inside court premises and treating Awami League activists without ‘Innocent until Proven guilty’ shows the reality. The fairness of judiciary and trials are being questioned, many believe the verdict is ready and interim is just buying time for retribution.

The Amendment to repressive Anti-Terrorism Act

The newest update to the Anti-Terrorism Act really hits hard against free speech and the right to protest. First off, now the government can ‘temporarily suspend’ any group they suspect of being involved in terrorist activities, on top of their previous power to ‘prohibit’ an organization under Section 18. These powers, which previously only applied to prohibited groups under Section 20, now extend automatically to those that are suspended.

This means they can shut down offices, freeze bank accounts and assets, stop members from leaving the country, seize belongings, and even ban any public support or displays of solidarity for the group. Basically, the government can now quickly neutralize a party or organization with just a ‘temporary suspension,’ without having to go through the more permanent ‘prohibition’ process. But here’s the catch—how long does a ‘temporary’ suspension last? The law doesn’t say so, so in practice, it could go on forever, even if they call it temporary.

On top of that, they’ve massively expanded their power to prevent people from supporting or advocating for these groups under Section 20(e). It now clearly states that publishing statements, promoting online or through social media, or organizing marches, meetings, or press events in favor of or supporting the group is strictly forbidden. It’s an alarming step up in control, with serious implications for anyone speaking out or showing support.

Why Banning without referendum?

The Awami League, Bangladesh’s oldest and most influential party, was banned by the interim government without holding a referendum, even though surveys by Voice of America and others showed that most Bangladeshis didn’t support such a ban. While the interim authorities justified this move by citing the Anti-Terrorism Act and mentioning ongoing investigations into alleged crimes by Awami League leaders, they didn’t seek any direct public approval or hold a plebiscite. This has raised questions about whether the move really reflects democratic legitimacy.

Although the Awami League has faced serious accusations of electoral misconduct in the elections of 2014, 2018, and 2024, it has previously won allegedly free elections under caretaker governments, which shows it has broad support. In this case, it seems to be a victim of exclusion by an interim administration that has never gone to the electorate, not even at the local council level.

Gloomy path towards transition

Bangladeshi democracy has always been a bit of a balancing act—it’s fragile, often disputed, and shaped by deep mistrust among the parties involved. The accusations against the Awami League, whether it’s about election rigging or acting too heavy-handed, aren’t something new; they reflect a broader political culture where holding onto power sometimes seems more important than following the process.

Under the ban, millions of Awami League voter’s political rights are pretty much gone. Any kind of support for the Awami League—whether you say it out loud, write about it, or post online—could be considered a crime. Even just social meetings peacefully with other supporters might get you arrested. Prior to the ban, Bangladesh recently went multiple notches downward in the democratic index by the Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU).

Disclaimer: Views expressed by writers in this section are their own and do not reflect Milli Chronicle’s point-of-view.