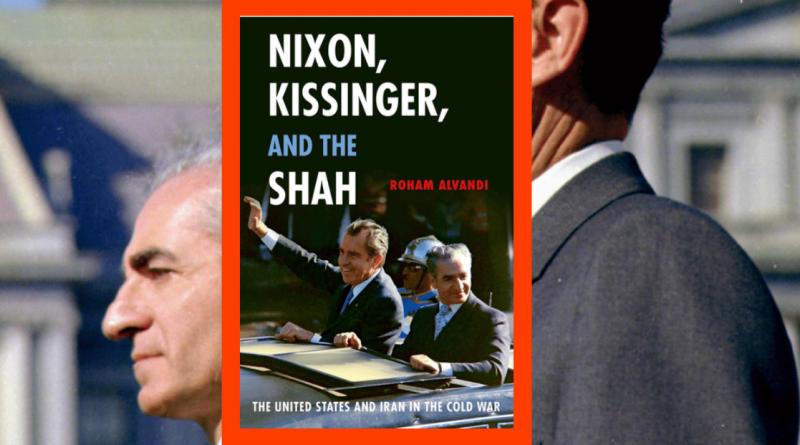

Book Review: Nixon, Kissinger, and the Shah—The United States and Iran in the Cold War

These episodes are not just milestones in U.S.-Iran relations, but also touchstones for Cold War geopolitics across the Middle East and South Asia.

Roham Alvandi’s Nixon, Kissinger, and the Shah is a compelling, rigorously documented study that challenges prevailing Cold War narratives by reinterpreting the power dynamics at the heart of the U.S.-Iranian alliance in the 1970s.

Meticulously drawing on Persian-language sources, newly declassified U.S. archives, and Iranian records, Alvandi offers a portrait of Mohammad Reza Shah Pahlavi not as a passive client of American imperialism, but as an assertive regional actor who helped shape the course of U.S. foreign policy under President Richard Nixon and Secretary of State Henry Kissinger.

At its core, the book traces the evolution of Iran’s status from a Cold War client to a strategic partner. In the 1950s and 1960s, successive U.S. administrations — Eisenhower, Kennedy, and Johnson — had viewed Iran as a subordinate state within a Cold War patron-client model.

This view was rooted in the CIA-backed 1953 coup that ousted Prime Minister Mohammad Mossadegh and reinstalled the Shah. From that moment, the United States exercised tight control over Iran’s military ambitions and regional behavior, often treating the Shah as an expendable buffer rather than a respected peer.

But as Alvandi shows, this dynamic fundamentally shifted with Nixon’s rise to power. The Nixon Doctrine, born of the trauma of Vietnam and the British military withdrawal from the Persian Gulf, reimagined America’s Cold War strategy in the developing world. Rather than direct military intervention, the U.S. would rely on trusted regional powers to police their own neighborhoods.

For the Persian Gulf, Nixon selected Iran and Saudi Arabia as the “twin pillars” of regional stability. But under Nixon’s leadership — and thanks to a long-standing personal relationship forged during Nixon’s 1953 vice presidential visit to Tehran — the Shah managed to elevate Iran above its supposed twin, lobbying the White House to prioritize Tehran’s interests and ambitions over those of Riyadh.

Alvandi emphasizes that this shift was not merely strategic, but personal and political. Nixon and Kissinger saw the Shah as a fellow Cold Warrior, a modernizing autocrat who shared their geopolitical worldview and opposition to Soviet influence. This mutual trust led to unprecedented levels of U.S. arms sales and diplomatic support.

In Chapter 2, Alvandi charts how Iran’s transformation into a U.S. partner coincided with Nixon’s rejection of a balanced Gulf policy. Iran was no longer to be merely one pillar — it would be the paramount power in the Gulf, armed and backed with little restraint.

Perhaps the most fascinating part of the book is its focus on three key historical episodes that map the rise and fall of the Nixon-Kissinger-Pahlavi partnership. These episodes are not just milestones in U.S.-Iran relations, but also touchstones for Cold War geopolitics across the Middle East and South Asia.

The first of these episodes centers on the 1971 Indo-Pakistan War, during which the Nixon administration, in violation of U.S. law, illegally funneled American arms to Pakistan via Iran. This backchannel operation exemplifies the depth of trust Washington placed in the Shah, who acted not only as a regional policeman but also as a clandestine logistics partner.

At the same time, the Shah’s decision-making during the 1969 Shatt al-Arab crisis with Iraq — which nearly sparked war — illustrates how empowered he had become to act without U.S. oversight.

The second episode, detailed in Chapter 3, is the zenith of the U.S.-Iran partnership, particularly between 1972 and 1975, when the Shah, in cooperation with Israel and with tacit U.S. support, backed a Kurdish insurgency against the Ba’thist regime in Iraq. Alvandi offers the first comprehensive history of this CIA-supported covert operation, highlighting how the Shah used American involvement to weaken Iraq’s position while strengthening his own in Khuzestan and the Persian Gulf.

Eventually, when Iran reached a favorable border settlement with Baghdad in 1975, the Shah abandoned the Kurds, a decision made independently and presented to Kissinger as a fait accompli. Kissinger, though privately frustrated, had no choice but to accept the decision, knowing the importance of the Shah’s partnership to American regional strategy. The betrayal of the Kurds was a bitter consequence of realpolitik — but it was the Shah, not Washington, who orchestrated it.

The final episode tracks the gradual unraveling of the U.S.-Iran partnership following Nixon’s resignation and the rise of Gerald Ford. Chapter 4 focuses on the failure of nuclear cooperation negotiations between 1974 and 1976, a pivotal moment revealing a widening rift. The Shah had hoped the United States would help Iran achieve nuclear parity with the great powers, especially after the oil price shock of 1973 dramatically increased Iranian revenues.

However, without Nixon’s personal backing, the Shah found himself increasingly isolated in Washington. The Ford administration, under pressure from Congressional critics and skeptical bureaucrats, refused to treat the Shah as an equal partner, reviving the old pattern of conditional support. In turn, the Shah felt alienated and embittered.

Here, Alvandi introduces one of the book’s most memorable insights: the Shah’s own perception of how the United States viewed him. He is quoted as complaining that America treated him “like a concubine, not a wife” — a metaphor that captures both his resentment of conditionality and his desire for enduring respect and strategic intimacy.

Far from being a puppet, the Shah emerges as a proud and independent actor who used the superpower alliance for his own vision of Iran’s primacy, and grew increasingly frustrated when Washington failed to reciprocate his loyalty with equal respect.

In sum, Nixon, Kissinger, and the Shah is a major contribution to both Cold War history and Middle Eastern studies. It demolishes the simplistic narrative of Iran as a mere U.S. client state, instead presenting a layered analysis of a shifting, often fragile, strategic partnership.

Alvandi writes with scholarly precision and narrative clarity, blending detailed archival research with geopolitical insight. By placing the Shah at the center of Cold War diplomacy — not as an accessory but as an actor — he forces readers to rethink the balance of agency in international politics.

This is essential reading for anyone seeking to understand not just the roots of the 1979 revolution, but the long, troubled history of mistrust and misperception that continues to shape U.S.–Iranian relations today.