FORGOTTEN TERROR: King Leopold II mutilated and massacred Black Slaves of Congo

Belgium is not the first European country we think of when we hear the words “blood-soaked tyranny.” Historically, the little country has always been more famous for beer than epic crimes against humanity.

But there was a time, at the peak of European imperialism in Africa, when Belgium’s King Leopold II ran a personal empire so vast and cruel, it rivaled – and even exceeded – the crimes of even the worst 20th century dictators.

This empire was known as the Congo Free State and Leopold II stood as its undisputed slave master. For almost 30 years, rather than being a regular colony of a European government the way South Africa or the Spanish Sahara were, Congo was administered as the private property of this one man for his personal enrichment.

This world’s largest plantation was 76 times the size of Belgium, possessed rich mineral and agricultural resources, and had lost perhaps half of its population by the time the first census counted only 10 million people living there in 1924.

Nothing about Leopold II’s youth suggested a future mass murderer. Born the heir to Belgium’s throne in 1835, he spent his days doing all of the things a European prince would be expected to do before ascending to the throne of a minor state: learning to ride and shoot, taking part in state ceremonies, getting appointed to the army, marrying an Austrian princess, and so on.

Leopold II took the throne in 1865 and he ruled with the kind of soft touch Belgians expected from their king in the wake of the multiple revolutions and reforms that had democratized the country over the preceding few decades. Indeed, the young King Leopold really only ever put pressure on the senate in his (constant) attempts to get Belgium involved in building an overseas empire like all the bigger countries had.

This became an obsession for Leopold II. He was convinced, like most statesmen of his time, that a nation’s greatness was directly proportional to the amount of lucre it could suck out of equatorial colonies, and he wanted Belgium to have as much as possible before other countries came along and tried to take it.

In 1878, Henry Stanley presumed to meet Dr. Livingstone deep inside the Congo rain forest. The international press made both men out to be heroes – bold explorers in the heart of darkest Africa. What went unsaid in the breathless newspaper accounts of the two men’s famous expeditions is what they were doing in the Congo in the first place.

A few years before the two expeditions met up, Leopold II had formed the International African Society to organize and finance exploration of the continent. Officially, this was a prelude to a kind of international philanthropic enterprise, in which the “benevolent” king would shower natives with the blessings of Christianity, starched shirts, and steam engines.

Stanley and Livingstone’s expeditions composed a major part of opening up the rain forest to the king’s agents. This ruse that King Leopold II was working overtime to get Africans into heaven, worked far longer than it should have and the king’s claim to the ironically named “Congo Free State” was formally recognized at the Congress of Berlin in 1885.

To be fair, it is possible that Leopold II, a fairly observant Belgian Catholic, really did want to introduce his new chattel to Jesus. But he did this in the most literal, and ruthless, way possible: by killing a huge number of them and making life generally unbearable for the rest as they labored to dig up gold, hunted to kill elephants for ivory, and hacked down their native forest to clear land for rubber plantations all over the country.

The Belgian government lent Leopold II the necessary seed capital for this “humanitarian” project – and after he paid that debt off, literally 100 percent of the profits went straight to him. This was not a Belgian colony; it belonged to one man, and he seemed determined to squeeze every drop out of his fiefdom while he still could.

Generally speaking, colonists need to employ some form of violence to acquire and maintain control of the colonized, and the more exploitative the arrangements on the ground, the more violent the colony’s rulers have to be to get what they want. During the 25 years that the Congo Free State existed, it set a new standard for cruelty that horrified even the other imperial powers of Europe.

The conquest started with Leopold bolstering his relatively weak position by making alliances with local powers. Chief among these was the African Christian slave trader Tippu Tip.

Tip’s group had a considerable presence on the ground and sent regular shipments of slaves and ivory down to the Zanzibar coast. This made Tip a rival to Leopold II, and the Belgian king’s pretense of ending slavery in Africa made any negotiation awkward. Nevertheless, Leopold II eventually appointed Tip as a provincial governor in exchange for his noninterference in the king’s colonization of the western regions.

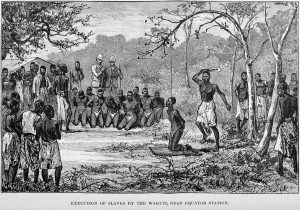

Tip used his position to ramp up his slave trading and ivory hunting, and the generally anti-slavery European public brought pressure on Leopold II to break it off. The king eventually did this in the most destructive way possible: he raised a proxy army of Congolese mercenaries to fight against Tip’s forces all over the densely populated areas near the Great Rift Valley.

After a couple of years, and an impossible to estimate death toll, they had expelled Tip and his fellow African slavers. The imperial double-cross left Leopold II in complete control.

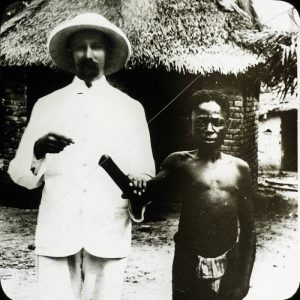

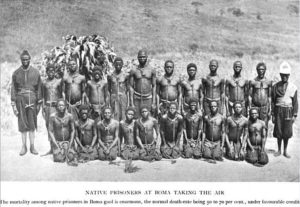

With the field cleared of rivals, King Leopold II reorganized his mercenaries into a ruthless group of occupiers called the Force Publique and set them to enforcing his will across the colony.

Every district had quotas for producing ivory, gold, diamonds, rubber, and anything else the land had to give up. Leopold II handpicked governors, each of whom he gave dictatorial powers over their realms. Each official was paid entirely by commission, and thus had great incentive to pillage the soil to the maximum of his ability.

Governors press-ganged huge numbers of native Congolese into agricultural labor; they forced an unknown number underground, where they worked to death in the mines.

These governors — vis a vis the labor of their slave workers — looted Congo’s natural resources with industrial efficiency.

They slaughtered ivory-bearing elephants in massive hunts that saw hundreds or thousands of local beaters driving game past a raised platform occupied by European hunters armed with half a dozen rifles each. Hunters used this method, known as a battue, extensively in the Victorian Period, and was scalable such that it could empty a whole ecosystem of its large animals.

Under the reign of Leopold II, the Congo’s unique wildlife was fair game for sport killing by almost any hunter who could book passage and pay for a hunting license.

Elsewhere, violence took place on rubber plantations. These establishments take a lot of work to maintain, and rubber trees can’t really grow on a commercial scale in an old-growth rain forest. Clear cutting that forest is a big job that delays the crop and cuts into profits.

To save time and money, the king’s agents routinely depopulated villages – where most of the clearance work had already been done – to make room for the King’s cash crop. By the late 1890s, with economical rubber production shifting to India and Indonesia, the destroyed villages were simply abandoned, with their few surviving inhabitants left to fend for themselves or make their way to another village deeper in the forest.

The greed of the Congo’s overlords knew no boundaries, and the lengths to which they went to gratify it were likewise extreme. Just as Christopher Columbus had done in Hispaniola 400 years earlier, Leopold II imposed quotas on every man in his realm for production of raw materials.

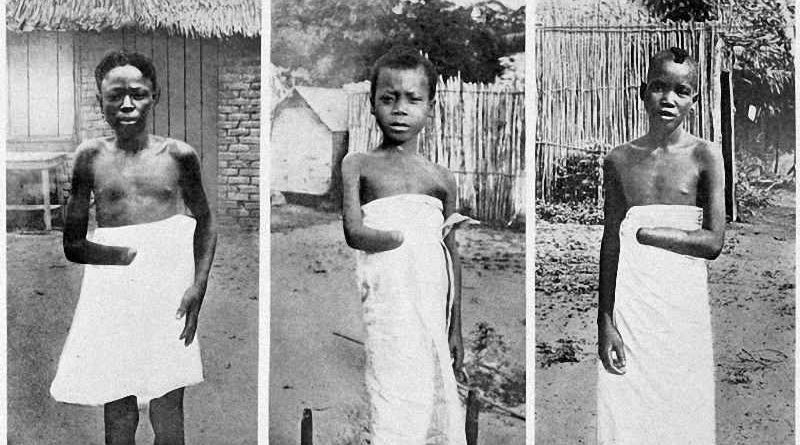

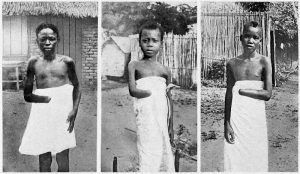

Men who failed to meet their ivory and gold quota even once would face mutilation, with hands and feet being the most popular sites for amputation. If the man could not be caught, or if he needed both hands to work, Forces Publique men would cut the hands off of his wife or children.

The king’s appalling system began to take its toll on a scale unheard of since the Mongol rampage across Asia. Nobody knows how many people lived in the Congo Free State in 1885, but the area, which was three times the size of Texas, may have had up to 20 million people before colonization.

At the time of the 1924 census, that figure had fallen to 10 million. Central Africa is so remote, and the terrain is so difficult to travel across, that no other European colonies reported a major refugee influx. The perhaps 10 million people who disappeared in the colony during this time were most likely dead.

No single cause took them all. Instead, the World War I-level mass death was mostly the result of starvation, disease, overwork, infections caused by mutilation, and outright executions of the slow, the rebellious, and the families of fugitives.

Eventually, tales of the nightmare unfolding in the Free State reached the outside world. People railed against the practices in the United States, Britain, and the Netherlands, all of which coincidentally owned large rubber-producing colonies of their own and were thus in competition with Leopold II for profits.

By 1908, Leopold II had no choice but to cede his land to the Belgian government. The government introduced some cosmetic reforms right away – it became technically illegal to randomly kill Congolese civilians, for example, and administrators went from a quota-and-commission system to one in which they received pay only when their terms ended, and then only if their work was judged “satisfactory.” The government also changed the colony’s name to the Belgian Congo.

And that’s about it. Whippings and mutilations continued for years in the Congo, with every penny in profit siphoned out until independence in 1971.

Just as many adults have a hard time overcoming a bad childhood, the Democratic Republic of Congo is still coping with trauma directly inflicted by the rule of King Leopold II. The corrupt commissions and bonus system Belgium put in place for colonial administrators stayed after the Europeans left, and Congo hasn’t had an honest government yet.

The Great African War swept over the Congo during the 1990s, killing perhaps 6 million people in the biggest bloodletting since World War II. This struggle saw the Kinshasa government overthrown in 1997 with an equally bloodthirsty dictatorship put in its place.

Foreign countries still own virtually all of Congo’s natural resources, and they guard their extraction rights with UN peacekeepers and hired paramilitaries. Virtually everybody in the country lives in desperate poverty, despite living in what is (per square mile) the most resource-rich country on Earth.

The life of a modern citizen of the DRC sounds like what you’d expect for a society that’s just survived a nuclear war. Relative to Americans, Congolese people:

- Are 12 times more likely to die in infancy.

- Have a life expectancy 23 years shorter.

- Make 99.24% less money.

- Spend 99.83% less on health care.

- Are 83.33% more likely to be HIV-positive.

Leopold II, king of the Belgians and for a time the world’s largest landowner, died peacefully on the 44th anniversary of his coronation in December 1909. He is remembered for his large bequests to the nation and the graceful buildings he commissioned with his own money.

[Author: Richard Stockton]