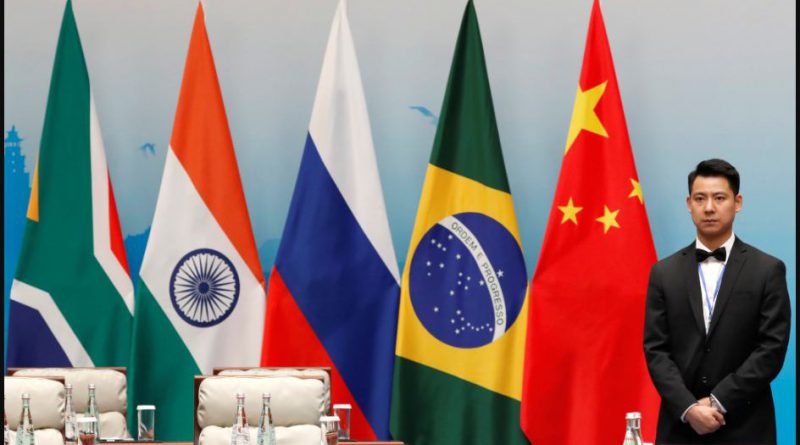

BRICS expansion hopefuls seek to rebalance world order

Reuters

Small countries hoping for an economic boost from BRICS membership might look to South Africa’s experience.

An expansion of the BRICS bloc under consideration at a summit this week has attracted a motley crew of potential candidates – from Iran to Argentina – with one thing in common: a desire to level a global playing field many consider rigged against them.

The list of grievances is long. Abusive trade practices. Punishing sanctions regimes. Perceived neglect of the development needs of poorer nations. The wealthy West’s domination of international bodies, such as the United Nations, the International Monetary Fund or the World Bank.

Amid widespread dissatisfaction with the prevailing world order, the pledge of BRICS nations – currently Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa – to make the grouping a leading champion of the “Global South” has, despite a dearth of concrete results, found resonance.

Over 40 countries have expressed interest in joining BRICS, say officials from South Africa, which is hosting the Aug. 22-24 summit. Of them, nearly two dozen have formally asked to be admitted.

“The objective necessity for a grouping like BRICS has never been larger,” said Rob Davies, South Africa’s former trade minister, who helped usher his country into the bloc in 2010.

“The multilateral bodies are not places where we can go and have an equitable, inclusive outcome.”

Observers, however, point to an underwhelming track record they say does not bode well for BRICS’s prospects of delivering on the lofty hopes of prospective members.

Though home to some 40% of the world’s population and a quarter of global GDP, the bloc’s ambitions of becoming a global political and economic player have long been thwarted by internal divisions and a lack of coherent vision.

Its once booming economies, notably heavyweight China, are slowing. Founding member, Russia, is facing isolation over the Ukraine war. President Vladimir Putin, wanted under an international arrest warrant for alleged war crimes, will not travel to Johannesburg and only join virtually.

“They may have over-inflated expectations of what BRICS membership will actually deliver in practice,” said Steven Gruzd from the South African Institute of International Affairs.

Developing World Discontent

While BRICS has not divulged a full list of expansion candidates, a number of governments have publicly stated their interest.

Iran and Venezuela, punished and ostracised by sanctions, are seeking to reduce their isolation and hope the bloc can offer relief to their crippled economies.

“Other integration frameworks existing on a global level are blinded by the hegemonic vision pushed by the U.S. government,” Ramón Lobo, the former finance minister and central bank governor of Venezuela, told Reuters.

Gulf states Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates see BRICS as a vehicle for a more prominent role within global bodies, analysts say.

African candidates Ethiopia and Nigeria are drawn by the bloc’s commitment to reforms at the United Nations that would give the continent a more powerful voice. Others want changes at the World Trade Organization, International Monetary Fund and World Bank.

“Argentina has insistently called for a reconfiguration of the international financial architecture,” an Argentine government official involved in the negotiations to join BRICS told Reuters.

‘Much Talk, Less Action’

BRICS public positions already reflect many of these concerns.

And as it seeks to become a counterweight to the West, amid China’s tensions with the United States and the fallout of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, growing its membership could lend the bloc and its global reform message more clout.

In the run-up to the summit, however, the grouping’s shortcomings are in the spotlight.

While BRICS leaders at the summit are expected to discuss a framework for admitting new members with China and Russia keen to forge ahead with expansion, others, notably Brazil, are worried about rushing the process.

The tangible benefits to joining, meanwhile, are waning.

The bloc’s most concrete achievement, the New Development Bank, or “BRICS bank”, has seen its already sluggish pace of lending further hobbled by sanctions against founding member Russia.

Small countries hoping for an economic boost from BRICS membership might look to South Africa’s experience.

Its BRICS trade has indeed increased steadily since it joined, according to an analysis by the country’s Industrial Development Corporation.

But that growth is largely down to imports from China, and the bloc still accounts for just a fifth of South Africa’s total two-way trade. Brazil and Russia together absorb a mere 0.6% of its exports and by last year, South Africa’s trade deficit with its BRICS partners had ballooned four-fold to $14.9 billion compared to 2010.

Such outcomes should give candidate nations pause, Gruzd said.

“Concrete achievements for BRICS are difficult to find. Lots of talk. Much less action.”