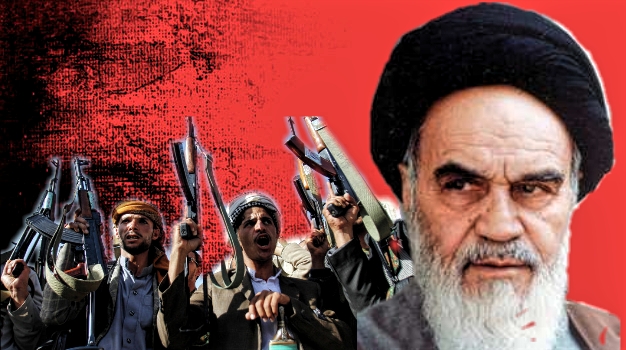

The Iranian Revolution still haunts its Survivors

by E Gheytanchi

She hadn’t always been afraid of the revolutionaries and the horror stories of the executions they committed.

I still remember the moment, 38 years ago, in the wake of the Iranian Revolution, when I overheard my mom tell my dad in a hushed voice that Dr. Parsa had just been executed. My mom’s shoulders were shaking and her voice was low. She said that the revolutionary forces had put Dr. Parsa in a burlap sack and shot her in cold blood. At the time, I did not know who Dr. Parsa was, but I knew that anything that could make my tough mother shiver like that — even after all we had endured in 1980 Iran — had to be horrific.

My mother, Ms. M. Dareshi, was the principal of Ettefagh, one of the most prestigious Jewish schools in Tehran during the 1970s and the early ’80s. This in and of itself was quite an accomplishment, as it was not easy for women to earn positions of power in Iran during the Pahlavi era. Despite the shah’s efforts to modernize Iran and promote women in government, the patriarchal culture was still a huge obstacle to the advancement of women in all areas of public life, including education.

Growing up in Iran, I remember how my mother would always rise before everyone in the house, slip on her dress and style her hair in the Thatcher fashion of those days. She used just enough lipstick and blush to look professional, but not enough to draw any extra attention. Teaching the Iranian Jewish children with their non-Jewish peers at Ettefagh was my mother’s calling. She was, and remains today, a dedicated teacher devoted to her students.

Back then, Farrokhroo Parsa was a trailblazer; she had advanced to become the first female minister of education in Iran. When the Iranian revolutionaries arrested her on charges of “spreading vice on earth and fighting God,” it was as if they were battling an ancient Persian mythic power. Her only crime had been to thrive as a successful woman, paving the way for the education of thousands, if not millions, of girls in a country that was (and remains today) both culturally and politically against the empowerment of women.

Parsa was highly educated, a physician by training, with a strong personality that inspired women like my mother.

I remember that my mom was particularly proud of a letter of appreciation she had received from Parsa in the years before the shah was overthrown. The letter was smartly framed and hung on our living room wall. But on that particular day in 1980 — in the midst of a revolution and at the beginning of the Iran-Iraq War — my mother destroyed it, afraid that it might tip off the revolutionaries to her true beliefs. It was not worth the risk.

As a young Jewish girl growing up in those scary times, I would try to understand what was really going on in my family. On the one hand, I was so proud of my mom — I used to brag about her to my friends. She was a rare woman in power, yet now she also showed signs of fear.

She hadn’t always been afraid of the revolutionaries and the horror stories of the executions they committed. Only a few weeks earlier she had secretly sent a message to Professor V., the father of one of the beloved Muslim students in her school who had become a supporter of a revolutionary Islamic-Marxist group called the Mujahedin-e Khalq-e Iran. The group had been under attack by the Islamists, who were solidifying their power after the revolution. My mother overheard a group of newly hired Islamist administrators say that 16-year-old Shahrzad (also written ‘Scheherazade’) V., a student at her school, had to be “eradicated” because she had fallen into the trap of Mujahedin-e Khalq — but she was not an active member of the political group, she was not even armed; she had merely been passing out political pamphlets.

My mom called all the students in her school “her children,” and my siblings and I were used to hearing her talk about yet another “child” for whom she had high hopes. Shahrzad V. was one of those children — smart, hardworking, beautiful and unwavering. As a young girl myself, I understood my mom’s mission: to educate and to give hope. So, of course she had to take a risk and warn Shahrzad’s father.

Shahrzad’s father received the message and tried to persuade his daughter to go hiding in Mashhad, a holy city in Iran where they had relatives. He also asked my mom not to contact their family anymore — he said he was worried about the consequences for anyone who had tried to save the “enemy of the revolution.” A few weeks passed before we learned that Shahrzad had rejected her father’s attempt to send her into hiding. She was arrested on charges of treason, just like many Mujahedin-e Khalq active members and their novice supporters, and sent to the notorious Evin Prison, where many inmates were known to have been tortured and killed.

The last we heard about Shahrzad was that she was raped in the prison and then executed. Apparently, Shahrzad’s executioners believed that killing a virgin was not approved in their narrow interpretation of Islam (Shiism). They therefore had to rape her before they “eradicated” her from the earth so that they — along with the virgin girls they killed — could go to paradise in the next world. Rumors spread like wildfire, but no one knew the exact circumstances.

Many years later, my mom told me Shahrzad’s dad could sometimes be seen near Ettefagh in torn clothes, kissing the steps of the school and wailing: “Where is my Shahrzad? She was innocent.” By then, he was no longer a respected professor at Tehran University; people said he had gone “mad.” Even though Shahrzad’s dad was Muslim, I imagined him dressed as the mythical figure of Wandering Jew, going around Ettefagh — cursed to walk aimlessly, searching for his daughter.

In the case of Dr. Farrokhroo Parsa, here was an outspoken woman who was not silenced until the very last minute of her life. In her so-called revolutionary trial, she was forced to wear the hijab but she remained truthful to her mission as an advocate of women’s rights. In her will, which was later published on the internet, she wrote:

I am myself a physician and know that death is nothing more than a moment. I embrace death with open hands and I am not willing to wear hijab for the sake of living a few more years or so; and I will not say “I regret” to stay alive and invalidate 50 years of struggle for the equality between men and women in this land with two simple words. I will never submit to wearing the hijab nor will I go one step backwards.

The day after her execution, there were rumors that she was not raped since she was a married woman with two daughters of her own; instead she was put in a potato sack and shot to death. Rumor had it that her executioners thought she was too filthy (najes in Persian) for them to touch, so they had put her in the sack in order to stay pure and to ensure their passage to paradise.

I was still in Ettefagh’s elementary school when all these events unfolded. My mom had not yet been replaced by a fully veiled Muslim woman who had been approved by the new revolutionary head of the ministry of education.

You might wonder how these ghastly events impacted the life of a young girl like me. I still cannot quite make sense of it all.

I have learned a lot. Life in that part of the world has a way of making one seem older than one’s age. In the West, we know and expect children to be protected and nourished. Sometimes they can even be reckless. I am a teacher myself now, too, and I come across college students who, in fact, do stupid things that they apologize for afterward. But these students are eventually forgiven. This is not so where I was born.

In Persian mythology, Scheherazade is the daughter of a wise vizier who makes a huge sacrifice in order to save the lives of her peers. When King Shahryar and his vizier discover that the queen has had a secret affair, the king gets angry and, in order to take revenge, orders his vizier to find one virgin girl every night so that his majesty can enjoy them in bed and then kill them in the morning. The vizier follows these orders for three years, until his own daughter steps up to the challenge, and after luring the king with her stories, which she weaves one after another as if constructing a maze, she marries the king.

You might have heard of this story as “One Thousand and One Nights” translated from Arabic or Sanskrit. The stories reflect the interconnected worlds of Muslims, Zoroastrians, Jews, Christians, Buddhists, Hindus and many other religions that co-existed peacefully then and continue to exist — though not so peacefully at present — in what is now known as “the Middle East.”

To me, an elementary schooler then and a mother now, the stories of the innocent 16-year-old Shahrzad V. who was raped and killed at Evin Prison, and Dr. Parsa, whose name in Persian literally means both “pure”/zahed (one who does no wrong) and “wise”/daneshmand (one who has wisdom), represented the bleak future of a revolution gone astray. Like the strong-willed young girl and the wise woman, my hopes were gone as Islamist zealots washed away everything they thought was impure and filthy.

I recall Shahrzad’s death as the time that I lost my childhood and was forced to become an adult. Fear was instilled in me that day — and, I believe, also in my generation. That fear grew stronger in me every day.

Now in my 40s, I am a worried woman and mother who has struggled with mood swings from time to time during my adult life. At least as I recall these stories, I understand some of the reasons behind my pain.

Yet, my story is not one of despair. I am alive and healthy. I have my own family now, a spirited 10-year-old daughter and a thoughtful 8-year-old son. I am happily married to the most patient and calm man I have ever known. Writing has become a great form of therapy for me. I can now give meaning to my life events, my deep sense of anxiety and my Jewish, Iranian-American identity. Without this search for meaning, life becomes an unbearably dull story. As Victor Frankel memorably wrote in his memoirs about Auschwitz, a life without a search for meaning becomes a dull one.

After all, let’s remember: Scheherazade never told a boring or simple story — because her life depended on it.

Article first published on Forward.com

E. Gheytanchi is an Iranian-American teacher and writer living in the United States. Born and raised in Tehran, she now teaches Sociology at Santa Monica College.