Beyond Good vs Evil: A Reader’s Take on “Son of Hamas” and the Cost of Conflict

The most powerful sections of Son of Hamas describe Yousef’s encounters with ordinary Israelis and Palestinians who refuse to kill….

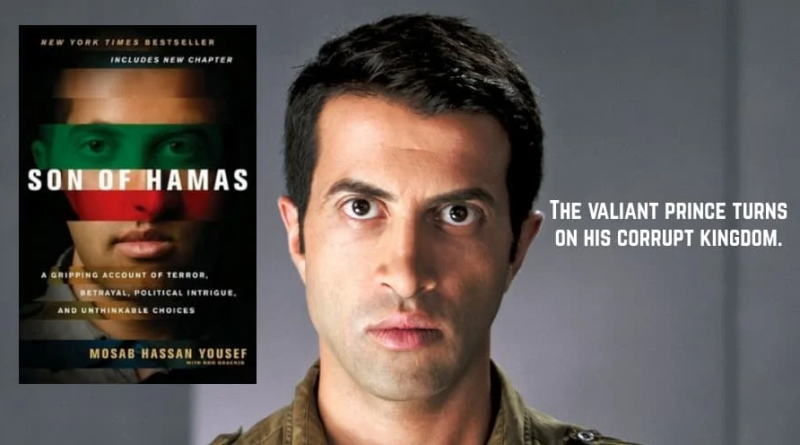

Since the announcement of the ceasefire in Palestine, my thoughts have instinctively turned toward Son of Hamas by Mosab Hassan Yousef. I’d been meaning to read it ever since a friend recommended it to me in late August. I finally sat down to read it four days ago — and it’s one of those rare books that leaves you troubled and thinking long after you’ve put it down.

In Son of Hamas, Mosab Hassan Yousef narrates one of the most morally fraught journeys of our time—the story of the son of a founding leader of Hamas who becomes an informant for Israel’s internal security service, the Shin Bet. The book is a profound and an insider’s reflection on one of the most complex human conflicts in modern history.

What stands out in Yousef’s account is not merely his personal reflections, but the human complexity he brings to the political tragedy of Palestine as the protagonist of his memoirs. He writes neither as a Palestinian nor as a sympathizer of Israel, but as a man shaped by ceaseless violence—prisons, bombings, raids, and death.

His politicization, unlike what is often imagined in Western commentary, does not stem from religious indoctrination but from lived experience: from watching his father, Sheikh Hassan Yousef, repeatedly arrested, imprisoned, and brutalized by Israeli forces. Politics, as Yousef’s story reminds us, does not grow out of ideology alone and primarily ; it takes root in suffering and in the injustices people endure in their daily lives.

Portrayal of his father might be deeply unsettling for Israeli readers. Far from the caricature of a fanatic and bloodthirsty cleric that dominates Israeli and Western discourse, Sheikh Hassan appears as a compassionate, devout, and humane man—a moral role model for a community often portrayed as barbaric and violent.

The dissonance between this portrayal and the over-demonized image of Hamas in mainstream narratives exposes the intellectual dishonesty that drives much of Western discourse. Israel, as experts point out, has inflated the image of Hamas to justify its militarization and continued occupation. The refusal to see humanity in the adversary is the first act of moral failure that sustains the cycle of violence.

Hamas’s ideology presents a profound obstacle to negotiated peace: its charter and public rhetoric leave little conceptual space for a permanent political settlement that recognises a Jewish national presence in historic Palestine.

That is not merely a tactical or strategic problem; it is a moral problem with no easy answers. If a movement’s stated aim is the elimination or delegitimization of ownership of land of a whole people, then conventional diplomatic tools — ceasefires, confidence-building measures, or even a two-state framework negotiated at elite levels — cannot by themselves resolve the underlying moral impasse.

Any political solution that ignores or paper-over these existential claims will be unstable at best and fraudulent at worst, because it fails to subject foundational ideas to the scrutiny they urgently require.

When Hamas consistently takes refuge in the Hadees of Prophet Mohammed in Sahih Muslim: “The last hour would not come unless the Muslims will fight against the Jews and the Muslims would kill them until the Jews would hide themselves behind a stone or a tree and a stone or a tree would say: Muslim, or the servant of Allah, there is a Jew behind me; come and kill him”.

Is any viable, durable political solution possible without directly confronting the religious texts and beliefs that many cite as justification for violence? If a scripture — widely read and accepted by a large community — is interpreted to endorse the destruction of another people, can we realistically expect those who are referenced to be killed to simply sit back and await their own predicted annihilation? This isn’t a fringe citation; it is drawn from material many Sunni Muslims regard as authoritative and prophetic.

If political strategy proceeds while ignoring such claims, can we honestly expect peaceful coexistence —Public debate must therefore address not only borders and security arrangements, but also the ideational premises that have been used to justify the killing and dispossession and continues to do so of so many innocent people.

The book offers no comfort to either side. Yousef’s critique of Hamas is scathing; he does not romanticize its militancy and calls it for what it is. Yet he insists that such movements do not arise in a vacuum. They emerge from genuine political grievances, collective despair, and the absence of any viable political solution.

To dismiss every act of violence as “terrorism,” without engaging meaningfully with the structural causes that produce it, is to perpetuate a conflict that has already consumed generations.

At one point, Yousef recalls how his friend Saleh was killed by the Shin Bet and the IDF, and how his Israeli handler, Loai, broke down, lamenting: “He really believed he was doing something good for his people.” That admission—from within the Israeli intelligence establishment—captures the absurdity of the conflict. When both sides believe they are doing good, ridiculous and genocidal slogans begin to masquerade as viable solutions, solution is the most difficult thing to come to.

Yousef’s reflections on the futility of the so-called “peace process” are particularly poignant. The Oslo Accords, and the idea of peace imposed from above, were always bound to fail because the masses on both sides had not reconciled to peace itself. When mainstream political space is suffocated, it inevitably gives rise to the fringes.

The most powerful sections of Son of Hamas describe Yousef’s encounters with ordinary Israelis and Palestinians who refuse to kill—not out of weakness, but out of conviction that every human life is sacred. He tells the story of a Jewish man who converted to Christianity and refused to serve in the Israeli army, enduring imprisonment for his belief that killing an unarmed human being violates the essence of his faith.

Yousef recognizes in this man a mirror of himself: someone who seeks to end violence, not perpetuate it. If such individuals multiplied on both sides, peace could one day become a reality.

Yousef’s honesty is also his tragedy. He is deeply naïve at times, believing that moral clarity can transcend the politics of power. His condemnation of suicide bombings, while morally correct, risks ignoring their political context. The bombers of the al-Qassam Brigades and other factions, however horrifying their acts, acted out of conviction that they were striking back against decades of occupation and humiliation. To understand such acts is not to condone them, but to recognize that they are not born of madness, but of genuine grievances that remain unaddressed to this idea and Israel has only worsened this crisis .

The Israeli and Western refusal to engage with that reality—the insistence on treating all Palestinian violence as irrational evil—has only deepened the wounds.

Israel’s strategy of assassination, collective punishment, and mass incarceration has not destroyed Hamas; it has made it stronger. The assassinations of leaders such as Sheikh Ahmed Yassin, Yahya Sinwar, and Mohammed Deif have not ended the movement, because Hamas is not reducible to its leaders. It is an organization rooted in the lived experience of occupation and the genuine concerns of the Palestinian people.

As Yousef notes, to think Hamas can be eliminated militarily is a dangerous delusion.

Son of Hamas ultimately reveals that both Israel and Hamas are trapped in a moral stalemate. Israel’s power is absolute, but its legitimacy is eroding. Hamas’s resistance is enduring, but its methods remain morally corrosive. Between these poles, the ordinary people—the ones who refuse to kill, betray, or dehumanize—remain invisible.

Yousef’s story, then, is not one of a Spy, as both Israelis and Palestinians have claimed. It is a story of impossible choices and moral courage, of a man who tried to humanize both sides and found himself alienated from each.

In the end, Son of Hamas forces us to confront a painful truth: no ideology, whether Zionism or Islamism, can contain the full humanity of those caught in its machinery. The challenge is not to destroy the other, but to recover the human within ourselves and try to work out a solution that could restore our humanity.

Disclaimer: Views expressed by writers in this section are their own and do not reflect Milli Chronicle’s point-of-view.