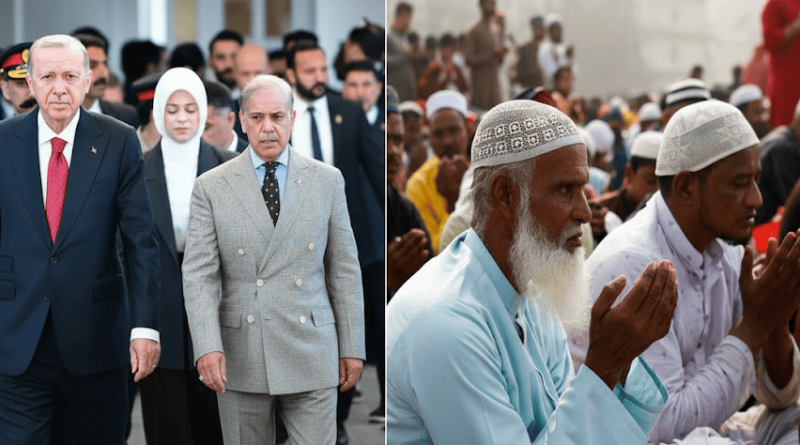

OPINION: Why Pasmanda Muslims Reject Pakistan’s “Ummah Unity” Narrative

Pakistan’s “Ummah message” is clear: solidarity is for wars and slogans, not for marriages, not for everyday equality.

The dream of Muslim unity—or Ummah solidarity—is often invoked in rhetorical, moral, and geopolitical terms. Yet for many Pasmanda and low-caste Muslims across South Asia, that narrative carries within it deep hypocrisy.

It asks suffering communities to rally, to protest, to pledge loyalty to a pan-Islamic identity, when in practice those same communities are neglected, excluded, or discriminated against by the very states and elites claiming to speak for all Muslims.

Caste, Discrimination, and Dissent within Pakistan

The critique of Pakistani “Ummah” rhetoric is not limited to India. Within Pakistan itself, low-caste Muslim communities—what some call “Pasmanda Muslims” there as well—face systemic discrimination rooted in caste-like hierarchies, structural exclusion, and social stigma.

Although Islam in its doctrine rejects caste, in practice the South Asian Muslim world has retained stratification. Scholars and activists have spoken openly of “Sayedism” or “Ashrafization” — the assertion by Sayeds or claimants to noble descent of superiority over lower-status Muslim groups.

In Pakistan, communities such as Mochi (traditional cobblers), Charhoa / Qassar (washer communities), and other artisan or “untouchable” lineage groups (sometimes Darzi, Dhobi, etc.) continue to experience social exclusion, discrimination in marriage, limited property rights, denial of equal respect, and denial of participation in religious authority circles.

An Al Jazeera commentary notes that literal violence, land grabbing, social ostracism, and the silencing of caste disputes in Pakistani media all serve to preserve an illusion that caste does not exist in Muslim society. The caste hierarchies are “publicly silenced but privately enforced”.

Thus, when Pakistani elites broadcast solidarity with distant Muslim struggles, but ignore or suppress demands from low-caste Muslims in their own society, the claim of universal Ummah becomes hollow.

It exposes a divide: those inside the circle of power receive moral voice, those outside it are silenced.

Elite Endogamy and the Hypocrisy of Solidarity

One of the most telling tests of true unity is marriage. In South Asian Muslim societies, marriage is a powerful vector of status, integration, and symbolic equality.

If the Ummah narrative were sincere, one might expect that Muslim elites—whether in Pakistan or India—would intermarry with deserving low-caste or Pasmanda Muslims, as evidence of transcending internal hierarchies. But that rarely happens.

In both Indian and Pakistani Muslim societies, Ashraf (so-called noble or high status) elites typically marry among their own lineages: Sayeds with Sayeds, Sheikhs with Sheikhs, Mirzas with Mirzas. Marriages across caste lines—especially downward—are extremely rare and usually stigmatized.

Anecdotally and observationally, it is almost unheard of for Ashraf elites to openly marry women from Pasmanda communities, or to give wives’ daughters to men from marginalized Muslim castes. Why? Because endogamy is both a social ritual and a power mechanism: it maintains status boundaries, control over lineage, and cultural prestige.

When those elites then preach Ummah solidarity, insisting that Muslims everywhere must unite under one banner, they are demanding emotional allegiance from those whose own status they refuse to cross. It is a double standard: unity in rhetoric, exclusion in practice.

That hypocrisy is especially stark when these elites use Pakistan’s foreign policy or missionary zeal to rally Muslims in India, Afghanistan, Palestine or elsewhere, while shunning egalitarian social relations even within their own societies.

Pakistan’s “Ummah message” is clear: solidarity is for wars and slogans, not for marriages, not for everyday equality.

The Indian Muslim Exclusion from OIC & the One-Sided Cry for Ummah

Consider first the status of Indian Muslims in the broader Muslim world. India is home to perhaps the world’s largest minority Muslim population—over 150-200 million by many estimates.

Yet curiously, Indian Muslims have never enjoyed institutional voice in the Organization of Islamic Cooperation (OIC). The OIC, which claims to represent the collective interests of Muslim nations, has never granted India—even as a non-member Muslim country—a meaningful seat, even consultative status, or real influence in its policymaking.

Critics point out that at the 1969 Rabat Islamic Summit, India was invited, but under pressure from Pakistan was made to withdraw. Pakistani diplomacy and influence have long insisted that India’s Muslim question be mediated through Islamabad’s narratives.

As Middle-east expert Zahack Tanvir puts it, “in five decades … Indian Muslims have never had a seat at the table of the OIC”, leaving India’s vast Muslim population institutionally invisible.

This exclusion is not a mere oversight. It is a structural marker: Indian Muslims are asked repeatedly to “stand for Ummah” in speeches, protests, diplomatic gestures, yet in the actual halls of power they are never granted membership or say. As Zahack aptly asked: “why do Indian Muslims continue to sacrifice … for a ‘brotherhood’ that has consistently ignored and sidelined them?”

The pattern is obvious: Pakistan claims to champion Muslim causes abroad—Kashmir, Palestine, Rohingya—but excludes the very Muslims living inside India from its leadership of that narrative. How can Muslims be united under a banner that denies agency and representation to hundreds of millions at home?

Toward a Sincere, Inclusive Ummah

This critique does not deny the spiritual or moral appeal of Muslim unity. Many Pasmanda Muslims, Indian or Pakistani, do believe in a compassionate Ummah—one of mutual responsibility, equitable rights, and shared dignity.

But they reject the version of Ummah unity that is selective, hypocritical, and exclusionary.

What is demanded instead is an Ummah that begins by correcting the wrongs within: by recognizing the agency of excluded Muslims, by ensuring representation (for example, including Indian Muslims in OIC deliberations), by dismantling caste‐style hierarchies, by encouraging cross-caste marriages as a lived symbol of equality, and by ensuring that solidarity is not just turned outward but applied inward.

Until then, the rejection of Pakistan’s narrative by Pasmanda and low-caste Muslims—whether in India or Pakistan—is not a rejection of faith, but a rejection of being asked to wear unity as a hollow mask.

Real unity must include the oppressed, not merely summon their voices while denying them power.

If you like, I can prepare a version of this for Pakistani audiences, or include more incisive case studies or interviews.

Disclaimer: Views expressed by writers in this section are their own and do not reflect Milli Chronicle’s point-of-view.