Feeling abandoned by Europe, Greece hardens migration policy

Ritaona (Reuters) – With walled camps and tougher border controls, Greece is hardening its approach ahead of summer when migrant arrivals pick up, defying criticism from aid groups and saying it has little choice given a lack of support from the rest of Europe.

The squalid conditions facing many asylum-seekers were laid bare last year when a fire devastated the sprawling Moria camp on Lesbos, and Greece has denied repeated accusations that its coast guard vessels have pushed back migrant boats as they entered Greek waters from Turkey.

Migration Minister Notis Mitarachi says the government is taking a tougher approach “so we don’t send the wrong message of incentivizing people to come” to Greece.

“Our policy is strict but fair,” Mitarachi told Reuters.

Greece was the frontline of Europe’s migration crisis in 2015, when a million refugees from Syria, Iraq and Afghanistan landed. The numbers have slowed sharply since, but Greece says it is still left shouldering much of the burden.

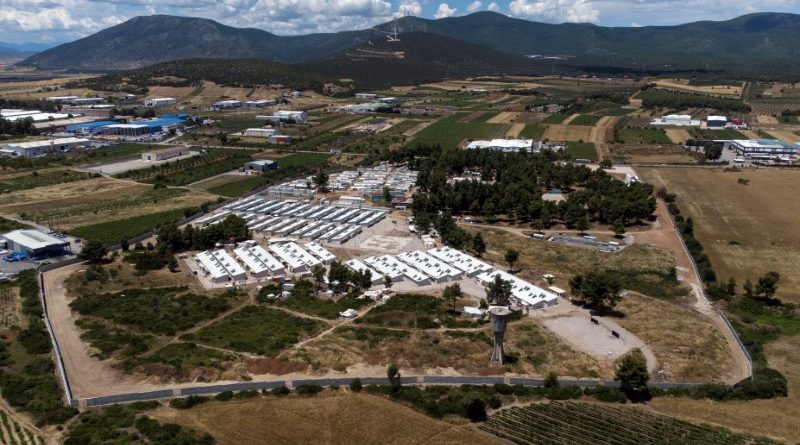

Outside Athens in the camp of Ritsona, signs of the stricter policy are visible. Concrete-fenced, it resembles a small walled town, with makeshift grocery stores, a butcher and a cafe blasting Arabic music.

For many asylum-seekers, it feels like a prison.

“Before, we were in an invisible jail. Now it (is) a visible jail,” said Liban, who fled Somalia in 2018 when drought and ongoing conflict left half the population without food, water or shelter. He asked that his full name not be used because his asylum application was pending.

In addition to fencing off camps, Greece launched an EU-wide tender in June to build two closed-type facilities on the islands of Samos and Lesbos, where the former occupants of Moria are housed on an abandoned army firing range.

Athens says the measures will make camps safer but aid groups say containment policies hurt people already traumatized by war and conflict. The Council of Europe’s Human Rights Commissioner has urged Greece to reconsider.

Obsession with difference

Medical charity Medecins Sans Frontieres said a “policy-driven humanitarian crisis” was unfolding on the five islands near Turkey, where it treated more than 1,300 people, a third of them children, for mental health issues.

“This obsession with deterrence and the obsession of control and at the same time, zero investment in integration, is only causing pain and nothing else,” MSF’s Greece director Christina Psarra said.

Greece has been pushing EU countries for support over a proposed overhaul of EU migration rules. While EU funds are easing some of the burden, there is a lack of solidarity, Mitarachi said.

“We still feel we are alone – Greece, Italy, Spain, Malta and Cyprus, the five Mediterranean countries – in tackling the pressures from migration.”

For Amir, a 17 year-old Afghan who has learned Greek since arriving in Ritsona 18 months ago and wants to become a doctor, the price feels high.

“We feel we have been separated with the walls they have built,” he said.

Greece says its policies are bearing fruit. In the months through May, there were more returns than arrivals and flows were down 68%, the migration ministry said. The number of people in camps was down 71% since last May.

But with instability in Syria, conflict in Somalia and the Taliban gaining strength as international forces prepare to leave Afghanistan, the drivers of migration remain strong.

In June, Greece issued a decision designating Turkey a “safe country” for asylum-seekers from those countries, making it harder for their asylum requests to be approved.

Mitarachi said Greece granted asylum to qualified applicants but “we don’t want to be the gateway to Europe for the smuggling networks”.