Qatar’s Influence Creep Spreads to Africa – with a little bit of help from the White House

by Irina Tsukerman

Qatar is taking advantage of this impetus to push for an “African Spring” to bring its own candidates to the front, and to advance its economic and geopolitical agenda.

While Akbar Al-Baker, the Qatar Airways CEO, has denied the widespread outbreak of COVID19 (the corona virus) inside Qatar (most of the cases have stemmed from travel to Iran), and while the world is distracted with the ongoing panic related to addressing the pandemic, Qatar continues advancing its mission of influence, focusing on Africa. One of these goals is to challenge the Ethiopian Airways. To that extent, Qatar has bought a 60% stake in Rwanda’s new Kigali Airport, a 49% stake in RwandAir, and is in negotiations to become a competitor to other airlines that pick up a lot of local traffic, including Royal Air Moroc, and Egypt Air. The reasons for this push are both economic – Africa is a huge emerging new market with a lot of potential, and geopolitical, in that Qatar Airways is blocked from flying over the space of a number of Middle Eastern countries as a result of the Gulf Crisis.

The crisis started in June 2017, when a number of states, led by the Anti-Terrorism Quartet (KSA, UAE, Egypt, and Bahrain) announced air, sea, and land blockade of Qatar until such time as it accepts thirteen demands from the coalition, which included distancing itself from Iran, cutting funding to the Muslim Brotherhood and assorted terrorist organization, ceasing to host Muslim Brotherhood figures, shutting down Al Jazeera, a Qatar mouthpiece that has been widely used as a tool of Qatar’s foreign policy, particularly to incite against its regional rivals, and ceasing to meddle in foreign affairs of other GCC members and their allies. Qatar’s competition with UAE first extended to building naval bases in Africa; now it continues in the airlines arena. The race continues with the Emirati investment in Nigeria’s Ibom Air, and Saudi interest in the African airline industry.

That is a part of Qatar’s investment in airlines projects around the world, many of which, as it so happens, have extensive routes throughout Africa, or belong to countries heavily invested in Africa in various ways. These include Air Italy, Cathay Pacific, China Southern, International Airlines Group (Aer Lingus/British Airways/Iberia), and LATAM, and is considering investing in IndiGo and Royal Air Moroc. The Chinese connection is not a coincidence; China is both one of the great powers most associated with the influence push in Africa and itself is a target of Qatari investments. It is also seeking to partner with the Ivory Coast. Rumors are also circulating that Qatar is also to invest in Angola airlines.

Importantly, while in the past, Qatar Airways has had tensions with American Airlines, which accused the airline of unfair business practices, preferential government subsidies, and aggressive expansion in the United States, but more recently dropped the dispute, after two years renewing a codeshare with Qatar, and using the relationship to offer new routes to Africa, the Middle East, and India. What led to the sudden change of heart? In part, this stems from an announcement of a strategic partnership, which will no doubt bring financial benefit to the American Airlines, which had filed for chapter 11 in 2011. It had avoided a complete downfall by merging with US airways. Following that, AA had spent $12 billion on buybacks, and in the midst of the coronavirus travel slump, is looking for a bailout.

A codeshare agreement with Qatar Airways offers a revenue sharing arrangement, which could help address these and other future AA financial woes. This means the very unfair business practices and government subsidies which were such a headache for the American airline industry not so long ago, through this partnership, will turn to Qatar’s benefit. The new announced routes in Africa by AA offer additional access to Qatar, further advancing its mission. Qatar is corrupting the US airline industry and turning it into an agent of its geopolitical agenda through these strategic partnership as it has done in the recent past (and continues doing) with US media.

And the most interesting part of that is that the US government – or at least the White House – may have played a small part in this arrangement, when, according to the Unions, President Trump sided with Qatar Airways/Air Italy in the dispute over the government subsidies and unjust enrichment with the US airline workers. As a result, the CEOs of these companies, who attended the meeting that was supposed to resolve that dispute in the summer of 2019, walked away empty-handed. If you can’t beat them, join them, American Airlines figured and indeed, rather than going bust, joined forces with Qatar. It remains to be seen whether other US airlines will follow. Still, not everything in this arrangement has worked out in Qatar’s favor. Air Italy had to pull the plug on the joint venture after going bankrupt and having to be liquidated, and Qatar also had to cut several unprofitable long-haul flights to Southeast Asia. And Germany’s Lufthansa rejected Qatar’s courtship – at least for now.

Whether concessions and partnerships with other above-mentioned airlines were arrived at through similarly dubious methods and possibly corrupt intercessions by the heads of state, desperate for investment, is a question well worth asking.

The purchase of influence in developing African countries continues in a variety of other ways – through investments, humanitarian aid and project, business deals, and support for start ups in promising locations.

In the last few years, Qatar has also focused on pushing for development projects throughout Africa. It is also working with South Africa to develop an LNG terminal. The two countries also engaged in negotiations over direct links between their ports. That would expand trade between the two countries and also help circumvent Qatar’s current limitations related to the naval blockade by the ATQ and others. Qatar, an LNG exporter, is the richest country in the world per capita. It has recently bought up stakes in LNG exploration blocks from Total and assorted other oil companies in South Africa, Mozambique, Morocco, and Kenya, besides various countries outside of Africa, as Qatar seeks to ramp up its liquefied natural gas production, but also to become a leader in that space in Africa. And with the countdown to the 2022 FIFA World Cup in Qatar, Doha has already allocated over $1.5 billion for development aid in Africa, while pushing to expand trade ties with various up-and-coming countries. Doha has also invested to the tune of $200 million via the Qatar Investment Authority into Airtel Africa, the second biggest telecommunications company in the continent with a base of over 94 million customers.

In its battle for the hearts and minds of Ethiopia (particularly with respect to its advantageous stand off with Egypt over the planned Renaissance Dam, which if implemented according to Ethiopia’s vision, could ruin Egypt’s economy), Qatar invested $18 million into Ethiopia’s kidney center. Ethiopia recently walked away from the negotiating table over the future of the dam, after refusing to attend the US-brokered talks which were supposed to generate the final deal related to the project, which would affect the region. Why would Ethiopia suddenly renege on the talks after seeming to acquiesce to the terms? Perhaps Qatar’s intervention and expectation of an influx of funding for the center and possibly other projects contributed to this decision. Indeed, an Ethiopian Economic Forum held in Doha only weeks before this allegedly final round of talks underscored the “huge potential” for commercial and investment links between the two countries.

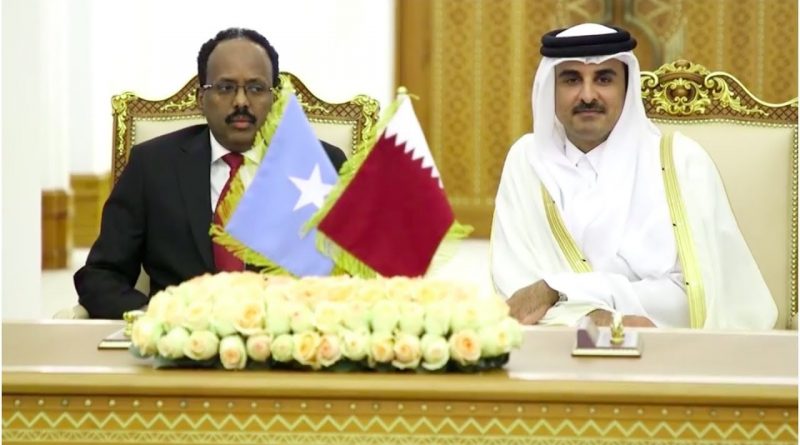

A business matchmaking event between the two countries also recently took place in Ethiopia, promoting trade & industrial relationship between the countries. Following these events, the Ethiopian PM abandoned his position of neutrality in Somalia, and joined up with Doha and Ankara in sponsoring the president, who has allowed various militant and jihadist groups to proliferate in the country, sowing potential to destabilize the Horn of Africa – and allow Qatar to take advantage of the chaos, as it has done in Libya. If Qatar bought influence in Ethiopia through investments with respect to Somalia, it is certainly possible that Doha has leaned in with respect to the change of position on the Renaissance Dam project, as well.

If Qatar’s involvement is to blame for Ethiopia’s intransigence, perhaps the United States could look past the narrow discussion of the existing deal and play a role in calling out Qatar and any other actor playing spoiler, while encouraging independent investors into various Ethiopian sectors that would address Ethiopia’s economic grievances and allow for the flexibility towards the timeline of the building of the dam, central to Egypt’s position on this matter.

But as it turns out, just like with China’s investments, Qatar help does not come for free. Its past investments into building a Kenyan port, for instance, has led to a deal which would give 40 000 hectares of land to Doha, potentially depriving a significant segment of local farmers from control over the land, and putting at risk a significant source of their income. The deal resulted in a protracted fight to salvage the land from reverting into Qatar’s possession. That story goes back to 2009, long before the Gulf Crisis. Such incidents have not endeared Qatar to Kenya, however, and neither has Qatar’s involvement in Somalia, where the arming of the militant groups threatens to flow over into Kenya and other countries.

Likewise, the Renaissance Dam project would be as important for Kenya’s energy development as for Ethiopia’s, and Qatar’s work to scuttle the deal threatens the livelihood of regular Kenyans. For that reason, Kenya leans towards Saudi Arabia, and while Rwanda’s head of state was negotiating tech and airline deals with Doha, Kenyan head of state was traveling to the “Davos in the desert” in the Kingdom. These diplomatic battles have not precluded Qatari banks from seeking deals with Kenyan companies, in Qatar’s persistent push to extend influence and presence even when and where it is not particularly wanted. And while Kenya’s political leanings are away from Qatar’s agenda, Qatar Petroleum signed exploration deals there and in Namibia, further expanding Qatar’s economic and business footprint in Africa. The Qatar Chamber meanwhile sought to attract Kenyan laborers to Doha, as well as to boost economic cooperation between the two countries.

THese include plans for constructing ports in Somalia (the Horn of Africa is strategically important to Turkey and Qatar), a country which already has a strong Turkish and Qatari influence.

However, Qatar’s looking towards Africa not only as a way to escalate economic rivalry with some of its Gulf rivals, but also in terms of projecting greater geopolitical influence, creating dependency, shifting policies in its favor, and exerting additional pressure on the ATQ. For a while, the boycott of Qatar contributed to Qatar Airways hitting a snag over expansion plans in Africa, and forcing it to postpone new destinations in West and Central Africa. However, while continuing to invest heavily in real estate (such as the recent Qatar Investment Authority partnership with Ascott to bring new property to Sydnia and to extend management and franchise contracts to Kenya and other countries around the world) , airline partnerships, and other sources of income around the world (and despite some heavy losses in some sectors), Qatar ultimately returned triumphantly to its plan, adding at least three new destinations just in the last months of 2019.

For instance, Qatar has formed a military alliance with Turkey, jointly funding militias in Libya for years after the overthrow of Qaddafi, and now being one other major backer of the “internationally recognized” Tripoli government with the pro-Muslim Brotherhood Fayez Al-Sarraj. Qatar was a transfer point for approved US arms shipments under the Obama administration that consequently ended up in the hands of Jihadis. It expanded military ties with Rwanda, and has recently invited a host of journalists from various African target countries, including Ghana, Nigeria, Ethiopia, Cameroon, Senegal, South Africa, and Kenya (in addition to Belgium), on a free propaganda trip to Doha, following which some started writing glowing articles about its suitability for the World Cup. Ideological and media outreach to African countries, influencing hearts and minds through such appeals, continues to remain the cornerstone of Qatar’s influence campaign.

Qatar had also played a meddlesome role in funding Omar al-Bashir and his Islamist government in Sudan for years. Following al-Bashir’s forced step down and apprehension, however, Qatar continued playing a meddling role in the country’s affairs behind the scenes. Qatar used Western propagandists to push for its preferred candidate, turned the transition period into anti Saudi campaign, baselessly accusing Riyadh of fueling attacks on protesters, and invited younger protesters to Al Jazeera to air their grievance, while distorting their comments and discrediting them in most of the Arab world. Qatar’s royalty also organized and funded a hashtag campaign related to the protests, which in the West was taken to be a grassroots movements, but in reality, promoted Qatar’s agenda among the protesters and their supporters in Western countries.

Qatar ultimately lost in Sudan, when the transition government, backed by Saudi Arabia, UAE, and Egypt ultimately prevailed and shut down Al Jazeera, and arrested Qatari intelligence officers who have arrived inside the country under journalist cover. The government ultimately proceed in ridding the country of Islamist influence from local offices just as much as from the top echelons of power. Far from admitting defeat, taking its marbles, and going home, however, Qatar moved on to its next purported target – Malawi, where Qatar’s Al Jazeera has been obsessively covering mysterious protests over the disputed election. The group organizing the protests, the Human Rights Defenders Coalition, appears to be grassroots and is led by a local chief, Timothy Mtambo, but just like in Sudan, some of the groups claiming to be focused on human rights, sprung up seemingly out of nowhere around the time of the 2019 election with an unclear source of funding.

This reflects the pattern of Qatar’s meddling in election related issues, where it gives outlet to local activists to speak on Al Jazeera and clandestinely finances the opposition and ad hoc “human rights” groups which appear legitimate to Western audiences unfamiliar with local issues, or Qatar’s foreign policy in Africa. Qatar’s involvement in and funding of human rights NGOs and think tanks around the world is well documented. Al Jazeera’s presence and angle of coverage in elections inevitably reflects Qatar government’s official foreign policy and interest in that outcome. Al Jazeera’s seeming sympathy with the opposition mirrors Qatar’s direct funding and backing of the losing candidate in Sudan’s post-Bashir campaign. Qatar is also rumored to have organized astroturf violent riots which are being passed for “peaceful grassroots initiatives”, mirroring the strategy it has utilized to some effect in Sudan. Qatar is also thought to have attempted to bribe several judges who reviewed the contested presidential election and ultimately annulled the results, citing a number of discrepancies, which had been debunked in the discovery proceedings after being systematically disputed by the lawyers for President Mutharika, and may have even been financing the opposition party. Some of the leadership in that party was part of the current government before a sudden and unexplained jump for an independent run.

But what is Qatar’s interest in Malawi? The current party in power is pro-Western and tough on immigration policy. Malawi is well positioned to revolutionize African economy by legalizing cannabis, and attracting potential investment into that sector from Gulf States. It is also an important source for mining minerals. That includes highly thought after minerals essential for the United States, which once had to be sourced from China: aeschynite and allanite. As the US trade war with China escalated, the State Department announced the shift in the US mining plans. These minerals are essential for development of hi tech, particularly advanced military equipment. And they are but two of 17 rare earth minerals recently discovered in Malawi. Besides that, Malawi is already a well known destination for precious stone and graphite. Chinese companies are already making inroads into Malawi, but with some pushback from the government which demands reciprocity in exchange for access to gemstones and minerals: building of schools, roads, and hospitals.

Qatar is looking to take advantage from this growing competition. Until recently, the United States showed very limited interest in Africa, despite all the potential, economic opportunities, and growing start-ups. Even the rich mineral and gemstone deposits only tempted some private US Companies. But geopolitical tensions with China shifted the policy, at least in a limited way. That, however, means that Qatar’s alliances can prove useful in shifting its relationships with both of the great powers, particularly in places where Qatar’s regional rivals have not yet made their presence known. In addition, nine other countries, including several African countries, and Brazil, all central to Qatar’s geopolitical influence strategy joined the US strategic initiative concerning these minerals. Is Qatar looking to develop its own defense industry, or at least, to gain access to its essential components? Even if Qatar is not, Turkey, its partner, is certainly looking into these options, especially following tensions with the United States and even China.

The race for these rare minerals comes at a time when young Africans in Sudan, Malawi, and others are looking for more “democracy”. Qatar is taking advantage of this impetus to push for an “African Spring” to bring its own candidates to the front, and to advance its economic and geopolitical agenda. For instance, gaining control of a small country with a mixed Christian and Muslim population, such as Malawi, would give it instant access to a near monopoly on these important minerals and create a dependency among other African nations and even Western states. None of that has anything to do with human rights for Africans, as Qatar has shown willingness to push protesters into greater danger in Sudan and other places, just to get international attention. Likewise, Qatar’s backing for Muslim Brotherhood parties in Egypt had little to do with the promise of freedom or human rights that most young Egyptian activists were looking at the time; it was manipulating grievances to advance its own agenda in bringing its ideological allies to political power.

The United States and other Western countries should not fall for Qatar-sponsored propaganda. Economic interests, hard and soft power, and Qatar’s political future are at stake, rather than a genuine interest in improving life for the locals in the African countries Qatar is courting. As can be seen from its ruthless power play in Kenya not so long ago, Qatar is interested in strengthening its own position without regard to the national sovereignty, dignity, or basic needs of the developing countries its deals are supposed to benefit. Far from being a human rights and humanitarian force with a big purse, Qatar’s Machiavellian push can sink any potential for civic growth and improvements in civil society building in Africa. While the United States snoozes and ignored most African countries, except some limited recent outreach to Egypt and Morocco in a variety of different fields, Qatar is expanding its influence, politically, economically, and ideologically, and none of it is particularly friendly to US interests or that of its allies. Perhaps it is time to wake up and rethink the US lack of presence in Africa, before Qatar’s self-serving scheming gets the better of every country that is hoping to utilize relationship building with African states towards some greater good.

Irina Tsukerman is a New-York based Human Rights Lawyer, National Security Analyst. She can be followed under @irinatsukerman.