The Future of US Aid to Africa: A Reset, Not a Cancellation

The end of USAID’s current aid structure should not mean the end of US support for Africa.

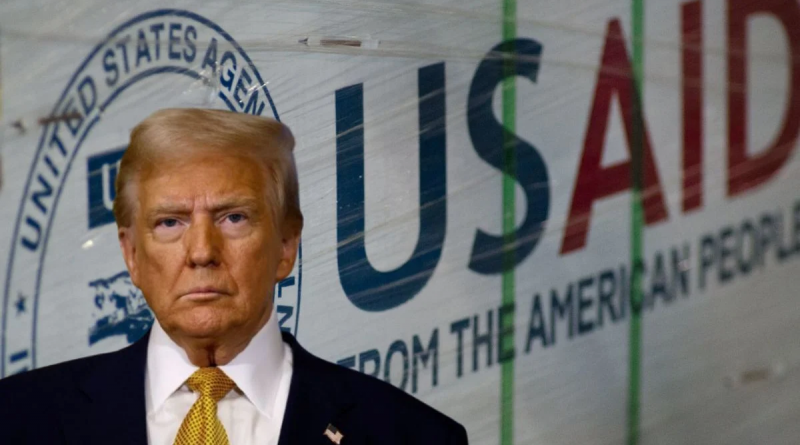

Even when it comes to international aid and assistance, strategic geopolitical interests are always at play. Recently, Secretary of State Marco Rubio announced the results of the review of programs carried out by the US Agency for International Development. This review resulted in an 83 percent cut in aid, significantly affecting many African countries. The decision has reignited debates about the ongoing competition between the US and China in Africa and the heightened risk of humanitarian crises that could arise from these funding reductions.

While competition for influence in Africa is a reality, framing it as part of a great power struggle is misleading. The US and China have taken vastly different approaches to engagement in Africa, and these cuts to USAID funding are unlikely to significantly alter China’s long-term strategy. Moreover, the presence of USAID has not deterred China from expanding its influence on the continent. Instead, the changes in US policy open the door for a fresh approach to American support—one that prioritizes African responsibility and transparency over unchecked aid flows.

According to the Congressional Research Service, sub-Saharan Africa has been the largest regional recipient of American foreign assistance. Over the past decade, the State Department and USAID have administered approximately $8 billion in aid annually to Africa. Countries such as Nigeria, Mozambique, Tanzania, Uganda, Kenya, and South Africa have been among the primary beneficiaries. In addition to direct US aid, African nations also receive assistance through other American agencies and Washington’s contributions to multilateral organizations.

Over the past decade, about 70 percent of American aid to Africa has been allocated to health programs, with a primary focus on HIV/AIDS. Additional funding has supported agriculture, economic growth, security, democracy promotion, human rights, and education. Several major initiatives, such as the US President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief, Feed the Future, and Power Africa, have been instrumental in addressing key issues. However, most aid is delivered through contractors, nongovernmental organizations, and multilateral bodies, rather than direct government-to-government assistance. This indirect distribution has created inefficiencies, as significant portions of the funds go toward administrative costs rather than directly benefiting the people in need.

This inefficiency is not unique to USAID; rather, it is a common issue in most foreign assistance programs and charitable organizations. A considerable portion of aid funds is used to cover operational expenses rather than achieving tangible results. The complexity of cross-border programs further exacerbates this issue, making positive change slower and less efficient. In the case of USAID, these inefficiencies have been particularly pronounced.

Despite these challenges, the US should not abandon Africa altogether. Instead, a recalibrated approach is needed—one that fosters real and positive change while reinforcing African leadership. The situation is somewhat analogous to Europe’s security dilemma, where strategic recalibration rather than complete withdrawal is the key. Africa deserves the generosity of the American people, but Washington must ensure that aid is allocated and executed in a manner that maximizes impact. This should be viewed as a reset, not a cancellation.

US aid policy must move beyond ideological motivations and focus on solving real problems while reducing Africa’s reliance on perpetual foreign aid. The ultimate goal should be to empower African leaders and institutions to take control of their economic future. Two key areas require immediate attention: poverty alleviation and the empowerment of local management. However, healthcare remains the most urgent concern.

Africa is paradoxically both a land of immense natural wealth and extreme poverty. Despite possessing some of the world’s largest mineral reserves—including gold, diamonds, platinum, copper, and uranium—many African nations continue to struggle with severe economic hardship. Control over these resources has historically been a source of military conflicts and external interventions. Similarly, Africa is a major producer of oil and gas, with countries such as Nigeria, Angola, and Algeria leading in petroleum reserves, while Libya and Egypt play significant roles in gas production. Additionally, Africa’s vast renewable energy potential, particularly solar power in the Sahara, holds the promise of transforming the continent’s energy landscape.

While Africa’s agricultural potential remains largely untapped, it is home to 60 percent of the world’s uncultivated arable land. It already leads in the production of commodities such as cocoa, coffee, tea, and timber. The region’s fisheries offer another source of economic promise. However, the reality is starkly different from these theoretical potentials. The disconnect between Africa’s resource wealth and its persistent poverty highlights the shortcomings of foreign aid and its structural inefficiencies. Rather than fostering self-sufficiency, aid has often perpetuated dependency while allowing external powers to gain control over resources in exchange for minimal infrastructure development.

This historical pattern has, in some ways, shifted the burden of economic responsibility away from African leaders and onto Western powers. In doing so, it has given external actors near-unfettered access to Africa’s wealth in return for relatively minor developmental contributions. By contrast, the Gulf Cooperation Council’s approach to engagement in Africa has generally been more pragmatic and mutually beneficial, earning it greater respect and acceptance.

For these reasons, the end of USAID’s current aid structure should not mean the end of US support for Africa. Any new American approach should prioritize helping Africa gain control over its own resources and development trajectory. This strategy should not be driven by a desire to counter Chinese or Russian influence but rather by the genuine spirit of American generosity and ethical responsibility. Such an approach would lay the foundation for a more sustainable and mutually beneficial US-Africa partnership.

A reformed aid strategy should focus on infrastructure development, technology transfer, and education to empower African nations to manage their own wealth effectively. Economic partnerships should replace traditional aid, ensuring that Africa is not merely the recipient of assistance but an active participant in its own development. Strengthening governance and transparency mechanisms will be crucial to ensuring that resources are used effectively and equitably.

The US has a unique opportunity to redefine its role in Africa. By shifting from a model of dependency-driven aid to one that fosters self-reliance, Washington can build a stronger and more lasting alliance with African nations. The ultimate goal should be to create a framework where aid is no longer necessary because African nations have developed the capacity to manage their resources and economies independently. In doing so, the US can demonstrate that its support for Africa is not just about competing with other global powers but about upholding a genuine commitment to the continent’s long-term prosperity.