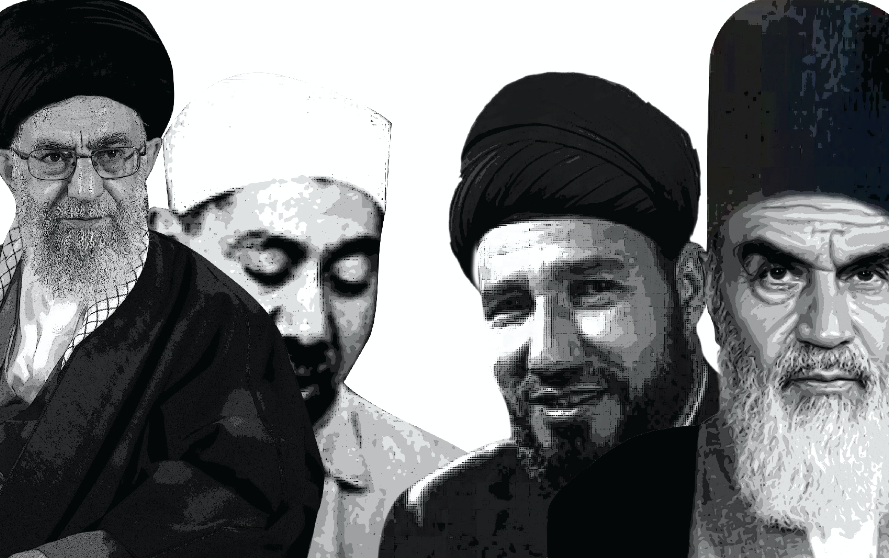

OPINION: The Tale of Two Ideologies—Iran and Muslim Brotherhood

The Muslim Brotherhood’s rule—unlike that of Khomeini—was short-lived.

In early 1979, the Iranian revolution came out victorious and Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi was ousted. A new regime was installed in Iran, faced with domestic and outside challenges and obstacles. However, the new regime had a magical blueprint for survival: ideology and indoctrination.

These two bases have been present in the Iranian political arena—and manifested in the practices of the new regime’s state apparatuses—from day one. An Islamic constitution was approved, and all the opponents of the Islamists—leftists and clerics embracing quietism and opposed to Velayat-e Faqih—were brutally liquidated in more of inquisitions than normal, fair trials.

In parallel, the Muslim Brotherhood remained an underground political organization at that time, gaining some room of freedom under late Egyptian president Anwar al-Sadat, whom the Iranian revolution deemed a foe for hosting the shah at his last days before death. Years passed by. Sadat was assassinated and late president Hosni Mubarak succeeded him.

After a three-decade rule, he was ousted following a massive uprising whose spark started on January 25, 2011. The revolution brought change—and the Muslim Brotherhood. But the latter didn’t survive in office a single day after year one. Mohammed Morsi, who was picked by the group to run in the 2012 presidential election, was ousted in a military takeover. Thus, the Muslim Brotherhood’s rule—unlike that of Khomeini—was short-lived.

Here a question arises: Why did the Iranian revolution succeed in ruling the country for over four decades while the Muslim Brotherhood has failed miserably after just one year in office. Answers for this question, of course, abound. However, a few answers cite ideology as a reason—instead citing the Brotherhood’s political naiveness, the desire to build a clerical dictatorship, failure to build consensus with the opposition, among others.

But ideology is the chief reason why the Muslim Brotherhood has failed to rule Egypt. The organization, founded in late 1920s by Egyptian teacher Hassan al-Banna, doesn’t possess a solid ideological ground upon which it could build a viable political project. Commentators always argue that the Muslim Brotherhood is organizationally strong—but ideologically weak. But this line of argument has long remained embedded and it’s time to shed some light on it.

Another question arises about the Iranian ideology—purportedly the cause of the Iranian regime’s success in holding on to power for four decades despite the convulsions it has been experiencing, chiefly the war with Iraq (1980-1988) and the subsequent waves of sanctions due to the country’s nuclear program and support for terror in the Middle East and beyond. The Iranian regime’s ideology is established on the so-called Velayat-e Faqih theory. It’s the political theory coined by the revolution’s firebrand leader and the Islamic republic’s founder Ruhollah Khomeini.

In the years leading up to Iran’s 1979 Islamic Revolution, Khomeini formulated his theory of Islamic governance while living in exile in Iraq. This theory aimed to give the Shiite ulema, or clergy, political control over the Iranian state.

The Islamic Republic of Iran was built on the original theory in this book. Shiite post-Age-of-Occultation ideology that claims that Islam grants a faqih (Islamic jurist) custodianship over people is known as the Guardianship of the Islamic Jurist, also known as the Governance of the Jurist. Ulama who endorse the doctrine vary on the scope of custodianship.

According to one interpretation, guardianship should only be granted for non-litigious issues (al-omour al-hesbiah), such as religious endowments (Waqf), legal issues, and property for which no one specific individual is responsible.

There’s also the Absolute Guardianship of the Islamic Jurist. It maintains that Guardianship should include all issues for which Prophet of Islam and Shi’a Imam have responsibility, including governance of the country. The idea of guardianship as rule was advanced by the Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini in a series of lectures in 1970 and now forms the basis of the Constitution of the Islamic Republic of Iran.

The constitution of Iran calls for a faqih, or Vali-ye faqih (Guardian Jurist), to serve as the Supreme Leader of the government. In the context of Iran, Guardianship of the Islamic Jurist is often referred to as “rule by the jurisprudent”, or “rule of the Islamic jurist”.

But what about the Muslim Brotherhood? What is the political theory upon which they have been basing their decades-old activism? The Muslim Brotherhood has a core ideology, which is creating an Islamic state, an objective that the organization knows under the rubric ‘Mastership of the World’. However, it seems the organization doesn’t have purpose-built manifestos or books explaining the group’s political theory.

There’s a book titled ‘Messages of the Imam’ authored by Hassan al-Banna. But its topics vary, focusing instead on religious, didactic and jurisprudential matters rather than putting an emphasis on the political theory that lays the foundation for the group’s ideology.

This poor ideological theorization has created problems for the organization, leading to divisions and secessions at the times of political crises—which the group is accustomed to calling ‘trials’.

The Muslim Brotherhood has been suffering back-to-back setbacks, beginning with the assassination of the group’s founder in 1949 and the major crackdown the group experienced under Nasser. Ironically, the group is known for ‘incessant trials’ as well as ‘always making the same mistake foolishly twice’.

These failures, setbacks and losses have a common denominator: Ideological weakness. In fact, the Muslim Brotherhood is organizationally strong, with hundreds of thousands of followers operating within its ranks—not to mention the sympathizers.

The organization also has a strong and rigorous hierarchy. But all this monolithic structure gets easily demolished in times of crises due to the lack of a solid ideological ground on which the group could base its political project.

An additional manifestation of this ideological weakness is the leadership crisis the Muslim Brotherhood is going through. As it’s known, the era of a single, cohesive Muslim Brotherhood is over. There are two groups (Two Muslim Brotherhoods’), with each claiming to be the sole legitimate body representing the organization’s members.

If there’s a clear, solid ideology that governs the group, there would be no such division. The group lacks ideology, and the leadership that could employ such an ideology. And this is why the group has failed to retain power in Egypt, and this is why the ayatollahs in Iran has been ruling the country since 1979.

The bottom line: Strong and solid ideologies enable religious associations to build a sustainable political system, as is the case in Iran.

On the contrary, organization with a poor ideological underpinning fail to build such a long-term political system, suffering thunderous downfall as soon as this weakness is exposed, as seen in Egypt’s Muslim Brotherhood in the 2013 military takeover that followed massive protests demanding an end to the group’s rule.