China’s Ruthless Assault on Islamic Heritage: Mosques Stripped of Arabic Features

Communist party slogans were added to mosque walls, and prayer services now include speeches emphasizing the Communist Party’s legitimacy rather than Quran recitations.

The demolition and alteration of mosques across China have raised concerns about the erosion of religious freedom and cultural assimilation. Protests against the so-called “renovation” of Najiaying Mosque in Yunnan province met with riot police, leaving locals feeling a profound sense of loss.

Similar changes have been observed at Doudian Mosque near Beijing, where architectural features and Islamic motifs have been removed, and surveillance cameras have been installed.

The Chinese government justifies these modifications as part of an effort to modernize and “harmonize” the mosques with Chinese culture.

Inside the mosque, an exhibition located off the main courtyard features a prominent panel encouraging worshippers to “promote unity” and “oppose division”.

The panel draws inspiration from both the Koran and traditional Chinese thinkers. Despite the modifications made to the exterior, passages from the Koran are still visible within the mosque, and the prayer hall remains unaltered.

A local resident describes the mosque as neither completely Chinese nor foreign in appearance, reflecting a unique blend of influences.

However, satellite imagery reveals that over 1,700 mosques have been altered, stripped, or destroyed, particularly in regions with high Muslim populations. In Ningxia and Gansu provinces, more than 80% of mosques with Islamic architecture have had features removed.

The scale and systematic nature of these alterations have been exposed by an investigation by the Financial Times (FT), the first to document the extent of this policy. Newyork-based Human Rights Watch (HRW) has condemned these changes, arguing that they violate the freedom of religion enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

A report by the Australian Strategic Policy Institute also revealed the destruction and renovation of mosques in Xinjiang, with two-thirds of them modified since 2017. The Chinese government claims to respect and protect religious freedom, maintaining that renovations aim to protect and meet the religious requirements of worshippers.

China is home to approximately 20 million Muslims, including the Uighurs in Xinjiang and the Hui ethnic group. While the Uighurs have faced severe repression, the Hui Muslims have enjoyed relatively broader religious freedoms due to their perceived adherence to Chinese culture and language.

According to James Leibold, a renowned expert on China’s ethnic policies at La Trobe University in Australia, the Chinese state perceives the Hui Muslims as the “model Muslims”. They are considered “good Muslims” because they speak the Chinese language, adhere to essential aspects of Chinese culture, and are viewed as trustworthy by the authorities.

Hui Muslims are dispersed throughout China and have comparatively more extensive religious freedoms, especially when compared to Muslim communities belonging to Turkic groups like the Uyghurs.

However, Chinese authorities have implemented various restrictions on Islam in Xinjiang over the past two decades, beginning with surveillance and limitations on worship. Over time, the Uyghurs have faced widespread detentions in purpose-built camps, intense surveillance, and travel restrictions, actions that the United Nations has characterized as potential “crimes against humanity”.

Beijing argues that its policies in Xinjiang are necessary to combat terrorism, foster unity, and promote economic development. The promotion of shared cultural values has also been cited as a justification for the removal of non-Chinese elements from mosques in other parts of the country.

However, the sinicisation policy seeks to assimilate non-Chinese groups and religions into what is considered Chinese culture. The removal of mosque features is a visible manifestation of this policy, signaling a redefinition of the relationship between the Chinese Communist Party and religion.

Hui Muslims now fear that their religious freedoms will also be curtailed. The sinicisation policy aims to “Han-ify” all Muslims, eradicating Islam from their lives and suppressing prayer and religious study.

This cultural transformation has left Hui Muslims despondent and concerned about the increasing similarities between the treatment of Uighurs and other Chinese Muslims. While some believe that the situation will not escalate to the extent seen in the Uighur camps, the mood remains apprehensive.

Najiaying mosque, Yunnan (pictures before after)

Turning Point in China’s Religious Policies

China’s religious landscape has witnessed significant changes in recent decades, particularly affecting the Hui Muslim community.

Over the centuries, Hui Muslims have constructed mosques in diverse architectural styles, reflecting the cultural and temporal contexts of their construction. However, the Cultural Revolution in the 1960s resulted in the destruction of numerous religious buildings, including mosques.

After Mao Zedong’s death, a shift towards Arabic-style structures emerged. During the liberal era of Deng Xiaoping in the 1980s, there was a surge in mosque construction featuring domed prayer halls and tall minarets, reflecting an admiration for Arabic architectural aesthetics.

Scholars point to Xi Jinping’s ascension to the presidency in 2013 as a turning point in China’s religious policies.

As a leader from the Han Chinese ethnic majority, Xi has expanded the Communist Party’s control over various aspects of daily life, consolidating power to a degree not seen since Mao. His promotion of Han ethnic nationalism in the name of socialism with Chinese characteristics represents a departure from previous Communist party leaders.

In 2014, Xi Jinping emphasized cultural unity at the Central Ethnic Work Conference. The following year, he called for the “sinicisation” of religion in China, considering Islamic architecture and symbolism as threats to ideological purity and cultural security.

Xi’s perspective, according to experts like Leibold, views Islamic elements as dangerous due to their perceived foreign, anti-Han nature.

In 2017, the Islamic Association of China, a government body overseeing Islam, criticized mosques for “copying foreign styles”. Officials denounced the “Arabization” of mosques, citing excessive size and extravagant decoration, accusing them of wasting resources. The meeting emphasized the need for mosque architecture to align with national characteristics.

Two years later, the government formalized these sentiments in the “Five-Year Plan on the Sinicisation of Islam”. The plan aimed to standardize Chinese-style practices in Islamic attire, ceremonies, and architecture. It also called for the development of an Islamic theology with Chinese characteristics. Critics argue that these policies create an impression that Islam can never be “Chinese enough”.

Accounts from Hui individuals, such as Mohammed from Ningxia, recount the demolition of mosque domes despite local farmers’ attempts to protect them.

Communist party slogans were added to mosque walls, and prayer services now include speeches emphasizing the Communist Party’s legitimacy rather than Quran recitations. Procurement documents from local governments corroborate the experiences of Hui Muslim communities.

China’s religious policy shift extends beyond Hui Muslims. The government has targeted other religions as well, removing crosses from Christian churches and demolishing prominent religious sites like the Golden Lampstand Church in Shanxi province in 2018. The destruction of Buddhist monasteries in Tibet began before the implementation of the sinicisation policy.

The alteration of mosque architecture, the insertion of political messages, and the targeting of other religious groups raise concerns about religious freedom and cultural diversity in contemporary China.

Government Influence and Restrictions on Mosques

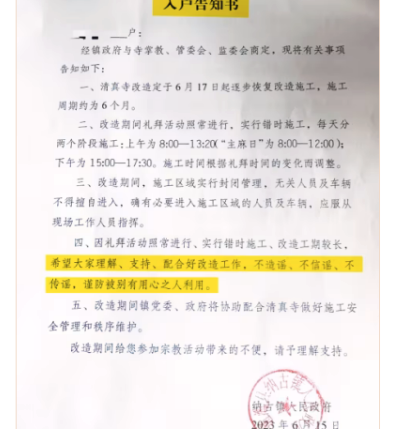

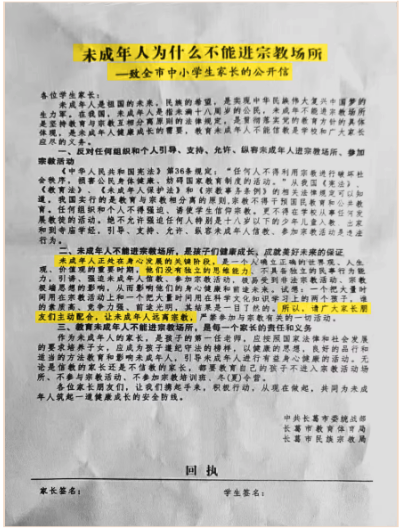

To control the influence of religion, the government has forbidden online material advocating religions to minors. Some local authorities have circulated notices prohibiting individuals under the age of 18 from entering religious sites or practicing religion altogether.

Additionally, current and retired civil servants have been informed that their benefits may be revoked if they engage in religious activities more than a few times per year. These measures have resulted in reduced attendance at mosques and limited religious participation.

In 2018, the government’s Islamic Association of China mandated that mosques organize patriotic activities, such as raising the national flag, and establish study groups focused on socialist values, the constitution, and traditional Chinese culture. These requirements aim to align religious practices with the government’s ideology and promote cultural unity.

Under the policy of “combining mosque congregations”, local governments have targeted mosques for consolidation and demolition. According to historian Theaker, this consolidation is justified based on the reduced attendance caused by the government’s restrictive policies.

Local government documents reveal that over a thousand mosques in Ningxia are under threat of consolidation, accounting for approximately one-third of all mosques in the province. The demolition of prominent mosques, such as the Weizhou Grand Mosque, has caused distress and sparked resistance among Hui Muslims.

In an effort to diminish Islamic visibility, various regions in China have removed Islamic symbols from public view. Additionally, Chinese state media reports that several regions have abolished halal certification standards, with officials associating the spread of halal markers on goods with religious extremism.

While some Hui Muslims have attempted to resist government actions, their efforts have often been met with suppression. Local protests temporarily delayed changes at the Weizhou Grand Mosque in 2018, and renovations to the Xiguan Mosque in Lanzhou city were postponed.

According to Bitter Winter, an online magazine focusing on religious freedoms in China, the remodelling of the Weizhou Grand Mosque commenced in 2019. Online photos indicate that by November 2023, local authorities in Gansu had removed the dome and minarets of the Xiguan Mosque.

However, the authorities ultimately prevailed, and the remodelling of these mosques began. Instances of protests being forcefully quelled, such as the riot police intervention at Ding’s Najiaying Mosque in Yunnan, highlight the challenges faced by those opposing government actions.

The analysis of 2,312 mosques in China provides valuable insights into the wide-scale modifications that have occurred between 2018 and 2023 as a result of the sinicization policy. The removal of Arabic-style features from 74.3 percent of the examined mosques indicates a significant shift in their architectural identity.

Despite resistance, Hui Muslims express concerns about the gradual decline of religion among younger generations and the competition between religious and modern lifestyles. The government’s success in suppressing religion raises fears about the future of Islam in China.