How Pakistan’s grand doctrine of ‘Strategic Depth’ has turned into ‘Strategic Disaster’

Pakistan now stands at a critical juncture. It can continue to treat Afghanistan as a battleground, striking across the border and relying on force to push back the militants.

For over four decades, Pakistan bet its security strategy on one idea: that Afghanistan could be controlled and turned into a “strategic depth” against India. The military and political elite in Islamabad treated Kabul as a buffer and a playground — a state to be manipulated through compliant regimes and proxy jihadist groups.

Militant networks were nurtured as instruments of foreign policy, and Pakistan believed this would secure influence across the region and check India’s power. Instead, the very forces Islamabad once empowered have turned against it. In 2025, the grand doctrine of strategic depth lies in ruins — a self-inflicted disaster now driving Pakistan’s worst security crisis in years.

Rather than securing Pakistan, Afghanistan has become the epicentre of the very dangers Islamabad once believed it could manage or manipulate. What was once perceived as an asset has now become a trap. The transformation of Afghanistan from strategic depth to strategic liability has unfolded gradually, but the past two years have made the shift undeniable.

When the Taliban returned to power in Kabul in 2021, Pakistan was widely seen as the external actor poised to benefit the most. Many within Islamabad believed that a Taliban government, because of historical ties, would be cooperative, deferential, and dependent. But that assumption now looks dangerously misplaced.

The Taliban’s political priorities have changed, their sources of external support have diversified, and their internal legitimacy depends on projecting a strong, independent stance — especially against Pakistan, which many ordinary Afghans still view with suspicion. Instead of shaping Afghan behaviour, Pakistan now finds itself confronting a volatile neighbour whose rulers no longer feel obliged to accommodate Pakistani interests.

Militant Blowback and a Hardening Border

Nowhere is this reversal clearer than in the surge of militant activity targeting Pakistan from Afghan soil. Over the past year, Pakistan has experienced a marked increase in terrorist attacks carried out by the Tehreek-i-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) and associated networks. Security reports from 2024 and 2025 indicated that many attackers either crossed over from Afghanistan or were trained and sheltered there.

Pakistani officials have repeatedly stated that a significant percentage of suicide bombers involved in major attacks were Afghan nationals. The data, while varying between sources, consistently shows a dangerous trend that the Afghanistan-Pakistan border has become increasingly porous to extremist infiltration, and many of these groups feel emboldened by their close ideological ties to the Afghan Taliban.

This is the central irony of Pakistan’s predicament. The militant ecosystem that Islamabad once supported for regional leverage has now splintered in ways that work against Pakistan itself. The TTP, originally an offshoot of groups nurtured under earlier Afghan policies, now treats Pakistan as its primary enemy.

Pakistan’s own creation has turned against its creator. The militancy that Islamabad once believed could be contained beyond its borders has now penetrated deep inside — striking security convoys, police units, and civilian targets with growing regularity. The blowback is undeniable.

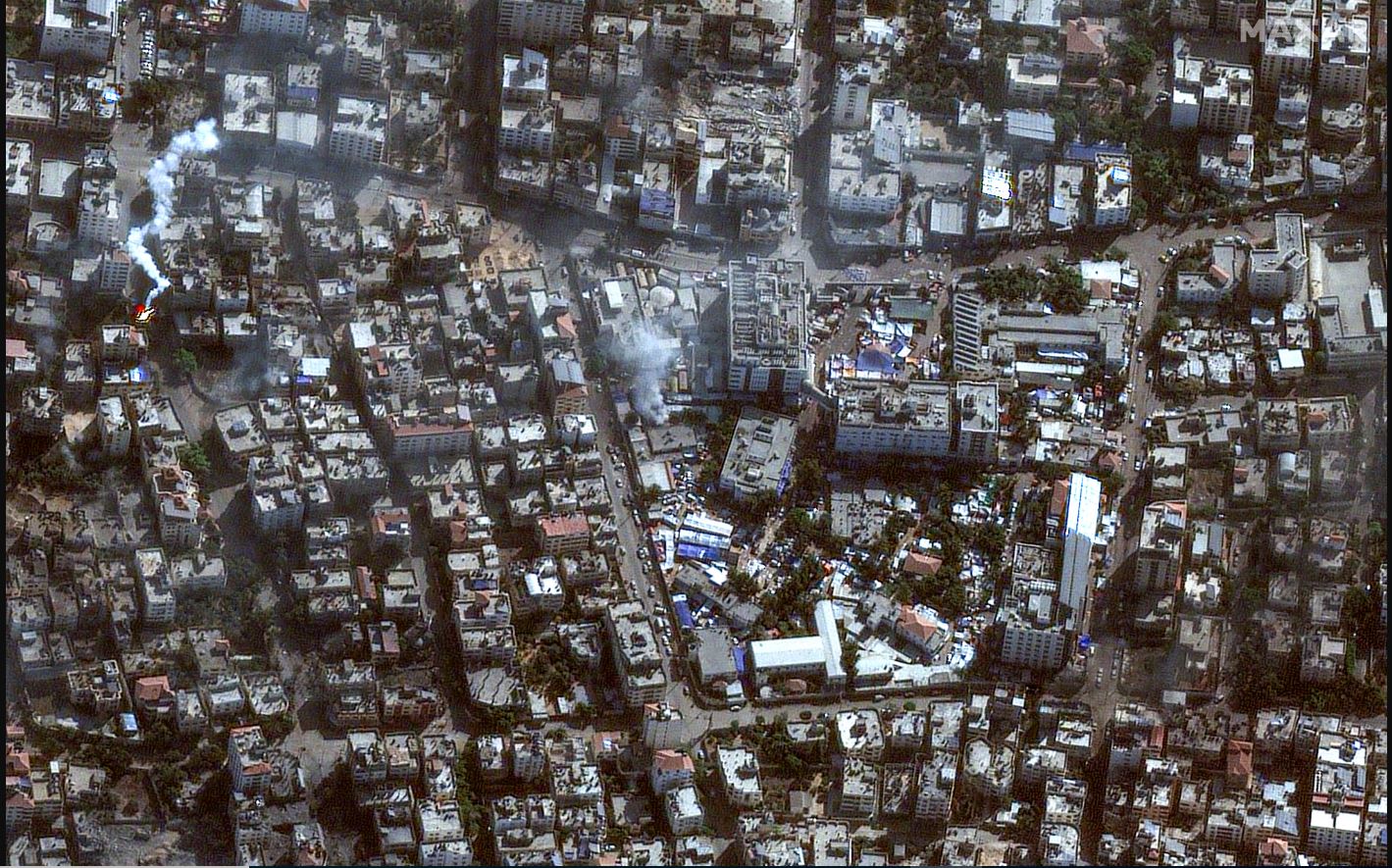

In response, Pakistan has increasingly resorted to military actions along — and across — the Afghan border. Throughout 2024 and into 2025, Pakistan conducted a series of cross-border artillery strikes and air raids targeting what it described as TTP safe havens. In several cases, those strikes hit areas inside Afghanistan, killing not only militants but also civilians, including women and children. These incidents have sharply escalated diplomatic tensions.

Kabul has issued multiple condemnations, arguing that Pakistan is violating Afghan sovereignty and inflaming anti-Pakistan sentiment among the Afghan population. What Islamabad once framed as necessary counterterror operations are now seen by many Afghans as external aggression, deepening hostility that already runs high.

Border clashes have also intensified. In late 2024 and through out 2025, firefights between Pakistani forces and Taliban border units became frequent, sometimes lasting hours. Pakistani officials reported significant casualties on their side, and Afghan authorities claimed similar losses.

The AfPak border — once envisioned as a controllable frontier from which Pakistan could extend influence — has hardened into one of the most militarized and unstable fault lines in South Asia. Instead of projecting strength, Pakistan finds itself in a defensive posture, its troops stretched and its internal security architecture under strain.

Diminishing Diplomatic Leverage and Growing Vulnerability

Diplomacy has not eased the tensions. Attempts at negotiation, including several rounds of high-level talks in 2024 and 2025, produced only limited agreements focused on border management and intelligence sharing. These arrangements have struggled to translate into real cooperation on the ground. The Taliban government maintains that it does not control the TTP, insisting that the group operates independently.

Pakistani officials reject that claim, arguing that nothing of significance can operate in Afghanistan without at least tacit Taliban approval. The resulting stalemate has left both countries locked in a cycle of accusation and retaliation.

Pakistan’s broader regional standing has also been affected. The international community has expressed growing concern about the escalating border violence, with several countries calling for restraint and renewed dialogue. Islamabad, once positioned as a key interlocutor between the Taliban and the West, now finds its diplomatic leverage diminished.

Meanwhile, the Taliban have sought new partnerships — particularly with regional powers seeking economic or strategic opportunities in Afghanistan. This reduces Pakistan’s ability to shape events in Kabul and signals a fundamental shift in the balance of influence.

The implications for Pakistan’s internal security are profound. The resurgence of terrorism within its borders has strained provincial administrations, especially in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and Balochistan. Police forces remain under-equipped, despite repeated calls for better resources. Public frustration is rising, particularly as attacks occur with worrying frequency.

Many citizens question the effectiveness of Pakistan’s long-standing policies toward Afghanistan and ask whether the sacrifices of the past two decades — military operations, casualties, and massive financial costs — have led to greater safety or merely deeper vulnerability.

The broader economic situation compounds the crisis. Pakistan’s financial struggles, including high inflation, energy shortages, and slow GDP growth, make it increasingly difficult to sustain prolonged military readiness along a volatile border. The costs of counterinsurgency operations, refugees’ management, and security infrastructure rise steadily even as state revenues remain limited.

Meanwhile, Afghanistan shows no sign of curbing the groups hostile to Pakistan. This asymmetry — a costly security burden with no cooperative counterpart in Kabul — underscores how Pakistan’s strategic depth has morphed into a strategic trap.

A Strategic Concept in Collapse

Yet the most troubling dimension of this trap is conceptual. Pakistan’s Afghan policy relied on assumptions that no longer hold: that Kabul could be influenced through patronage that militant groups could be calibrated for strategic use, and that Afghanistan’s internal dynamics would remain subordinate to Pakistani interests. The reality of 2025 contradicts each of these assumptions.

The Taliban now make decisions independently. Militant groups have become ideological actors rather than controllable proxies. Afghan nationalism, sharpened by decades of conflict, rejects external interference from any quarter — especially from Pakistan. The strategic logic underpinning decades of policy has evaporated, but its consequences persist.

Pakistan now stands at a critical juncture. It can continue to treat Afghanistan as a battleground, striking across the border and relying on force to push back the militants. But this would deepen the cycle of violence, alienating Afghan society further, and entrenching hostile networks.

Alternatively, Pakistan could pursue a significant recalibration — acknowledging the limits of influence, dismantling the remnants of proxy structures, and treating Afghanistan as a sovereign neighbour rather than a proxy regime. Such a shift would require political courage and institutional consensus, both of which have historically been fragile when it comes to Pakistan. But without such a rethinking, Pakistan risks sinking deeper into the trap of its own making.

The strategic depth that Islamabad long prized has become an illusion. Afghanistan is no longer a pliable sphere of influence but a source of hostility capable of undermining Pakistan’s security from within. The militants once cultivated as assets have become liabilities. The border once seen as a shield has become a wound. Pakistan’s Afghan dilemma is no longer about losing influence; it is about preventing the fallout from a potent threat to its own stability.

The question facing Pakistan in 2025 is not whether Afghanistan can be controlled but whether Pakistan can escape the strategic trap created by decades of miscalculation. Whether it will recalibrate before the trap tightens further is a question that will impact the region’s future also.

Disclaimer: Views expressed by writers in this section are their own and do not reflect Milli Chronicle’s point-of-view.