Syria’s election holds few surprises after years of war

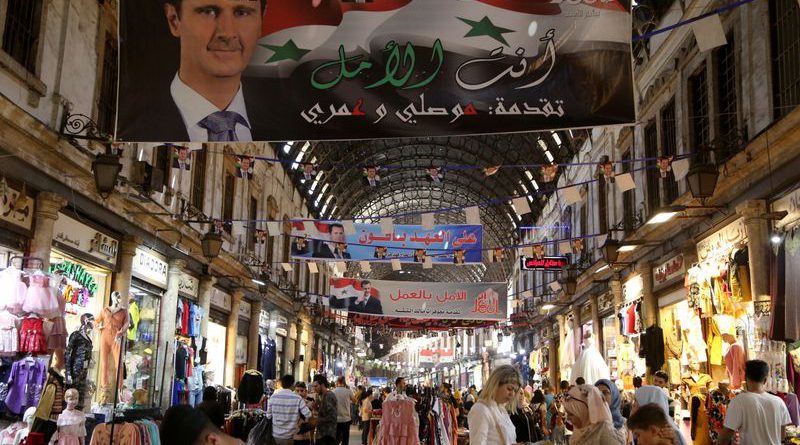

Amman (Reuters) – Campaign posters for Bashar al-Assad line the streets of Damascus, alongside those for two obscure rivals, but no one really doubts that Wednesday’s election will extend his presidency despite 10 years of war that has left Syria in ruins.

Ruled by his family for five decades, Syria is now barely recognisable from the nation that Assad, now 55, took over in 2000 after the death of his father, Hafez al-Assad.

When he began, the young eye doctor, who was belatedly groomed for office after his elder brother died in a car accident, promised a shift from his father’s iron grip – offering space to opponents and overtures to Western foes.

But reforms were swiftly buried and protests against his authoritarian rule erupted in 2011 as the Arab Spring swept across the region, turning into a conflict that has killed hundreds of thousands of people and driven 11 million from their homes, about half the population.

Assad has retaken control of much of his nation, where some voters will cast ballots this week at polling stations surrounded by bombed out buildings. But he has achieved this only with the decisive military help from Russia and Iran.

“If war imposes itself on our agenda, it doesn’t mean to prevent us from doing our duties,” he said on the Facebook account for his campaign, which has the slogan “Hope through work”.

But, for swathes of the country, their employment barely buys enough food. A shawerma sandwich, made from chicken or meat roasted on a skewer, was once the kind of snack people grabbed with little thought from a street cafe.

“Can you believe a shawerma costs nearly half my salary?” said Ali Habib, 33, saying it cost 20,000 Syrian pounds, while his monthly wage as a teacher in a state school is 50,000 pounds, or just over $16 at the unofficial rate.

Subsidised food has become a lifeline for many. Habib, who like others in Syria quoted in this article communicated with a Reuters correspondent outside the country, has had to sell some furniture to feed his wife and two daughters.

Message to the West

Western governments and Assad’s domestic opponents, many now abroad because they say it is the only way to avoid Syria’s pervasive secret police, or mukhabarat, view the vote as a choreographed affair to rubber stamp his rule.

“The country Assad is ruling is a shadow of the country that was Syria 10 years ago,” said Wael Sawah, a former political prisoner in exile in the United States. “The structure of society has changed as well as the economy too. It’s a shadow of what Syria was.”

Some Syrians say the vote aims to tell the United States, Europe and others that Assad is unbroken and Syria still functions, even amid pockets of fighting, mostly in the north.

“These elections are aimed at the West, taking the pattern of Western-style elections in one way or the other to give an ‘I am like you’ message,” said Maan Abdul Salam, who heads Syrian think-tank ETANA.

There has been nothing Western-style about past results. In the 2014 poll, official numbers had Assad securing almost 89% of votes on turnout of more than 73%, even though it took place amid fierce fighting. Critics dismissed it as a sham.

This year, Assad’s rivals are former deputy cabinet minister Abdallah Saloum Abdallah, and Mahmoud Ahmed Marei, head of a small, officially sanctioned opposition party.

Assad has also released hundreds of longtime supporters from judges to civil servants who were arrested earlier this year in a crackdown to silence critics within his loyalist camp.

Assad, who is from the tiny Alawite religious community, has all but crushed the insurgency in Syria, a majority Sunni Muslim nation. He has done so with the aid of Russia, which sent in warplanes, and Iran, whose support includes fighters from Hezbollah, the Lebanese Shi’ite group backed by Iran.

Turkey still holds territory in the northwest where millions live in squalid camps after fleeing Russian-backed bombardment, and there is a small U.S. military presence in the northeast, underpinning Kurdish rebels.

Containing Opponents

Before the war, Syria had a small but growing industrial base and produced modest amounts of oil from its northeast, now under Kurdish control, where most of its wheat was grown. Other food needs were met mainly from its fertile Mediterranean coast.

Now the economy has crumbled. Power cuts are longer than during some of the worst fighting, as the government lacks foreign exchange to import fuel. Inflation has soared.

“The situation today is not better from previous days when we lived under siege and bombardment,” said Abdul Khalek Hasouna from Moudamiya, a town near Damascus. “It was better than now.”

But Assad has contained his main opponents. Sunni rebels, the backbone of the insurgency, are largely hemmed into the north. There is little sign of new opposition in other areas.

Places like Ghouta, on the edge of Damascus, remain subdued. Western states and rights groups say Ghouta faced deadly gas attacks that killed hundreds after an uprising. Assad denies it.

To encourage any disenchanted loyalists, Assad has offered interest-free loans and one-off grants to state employees. State salaries have been hiked. But Western sanctions still bite.

“The economy won’t stand on its feet if economic sanctions are not lifted,” said Nabil Sukr, a Damascus-based economist.

During the war, Assad’s security services nurtured militias to help fight its battles. With the fighting subsiding, some disenchanted militia members say the groups have created powerful fiefdoms. Others complain they have not been fairly rewarded.

“My two brothers were martyred and what did we get? Nothing,” said Younes, a former fighter in a militia in Tartous on the Mediterranean, who only gave his first name.

Yet, for some Syrians, such as Habib on his tiny teacher’s salary, election or not, there is little choice.

“Life has become unbearable under Assad,” he said. “We used to look at him at as saint and now he is pushing us from stalwart supporters to silent opposition.”