OPINION: Israel-Turkey relations could be in for a change

by Seth Frantzman

Israel and Turkey once had excellent ties, the closest in the region.

A new Israeli foreign minister, Turkey’s battles in Idlib against the Iranian-backed Syrian regime and a convergence of necessity for dialogue in Syria and even the Mediterranean could point to a new leaf in Israel-Turkey relations after a decade of difficulties.

Israel’s Charge’ d’Affairs for Turkey, Roey Gilad, wrote a piece in Turkish media on Thursday that argues that Israel and Turkey have common interests.

Writing at Halimiz he noted that Iran’s presence in Syria works against Ankara’s interests and that Lebanese Hezbollah played a dominant part in the battle in Idlib where more than 50 [Turkish] soldiers lost their lives.

Evidence for this comes from foreign reports that “Israeli airplanes and drones are challenging Iranian military targets in Syria.”

Turkey and Israel do not have to agree on everything, he argued, there will remain many differences. COVID-19 and other challenges might work in favor of normalizing relations.

|

This includes trade, tourism, energy and academic cooperation. “The ball is on the Turkish side,” he notes at the end, because it was Turkey that expelled Israel’s ambassador in May 2018 after violence in Gaza and the US moving the embassy to Jerusalem.

Israeli radio stations discussed the oped that Gilad penned and it appears there are some issues that underpin a possible change in relations.

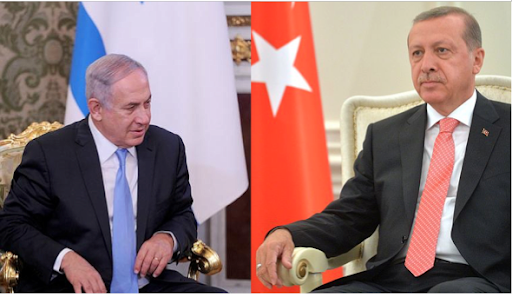

Israel and Turkey once had excellent ties, the closest in the region. But things changed over time, especially after 2009. Turkey had played a key role in talks with Syria, but the Gaza war and subsequent clash between Israeli President Shimon Peres and Turkish leader Recep Tayyip Erdogan in Davos, as well as a raft of other incidents from the Mavi Marmara to diplomatic spats, lead to a downward spiral in relations.

Israeli officials in October 2009 felt that formerly warm strategic ties had likely ended. Trade, which once numbered in the billions of dollars, continued, but much changed.

Where once Israel sold Turkey Heron drones, Turkey built its own formidable drone force. Ankara pushed for a more assertive posture in the Mediterranean as Israel worked more closely with Greece and Cyprus on a pipeline deal that was signed in January. Public spats over Palestinian issues and Turkey’s conflicts with Kurds continued on social media.

Turkey has led opposition to US President Donald Trump’s policies, such as the embassy move and the “deal of the century.” In December 2019 reports asserted that Hamas even plots attacks from Turkey. And there is the annual threat in Israel to recognize the Armenian genocide. There were attempts at rapprochement in the past.

In 2016 a deal with Turkey was supposed to bury wounds from the 2010 Mavi Marmara incident when Turkish activists were killed on a cruise ship trying to break the blockade of Gaza.

In recent weeks the new Israeli government and shifts in Syria, as well as Turkey’s growing role in Libya may have fed rumors about changes to come in Turkey-Israel relations.

Ostensibly these relations are still very cold because of Ankara’s views of Israel’s actions regarding the Palestinians. However Ankara’s ally in Qatar has worked with Israel in the past regarding funding for Gaza.

Qatar and Turkey are hostile to Egypt, the UAE and Saudi Arabia and in the last years there have been perceptions in the Middle East that Israel, the UAE, Egypt and Saudi Arabia share common interests relating to Iran and other factors.

In mid-May there were rumors on social media regarding Turkey’s role in the Mediterranean.

Turkey signed a deal with the Tripoli-based government in Libya. Libya is in the midst of a civil war and Ankara swept in to provide Tripoli much-needed assistance in exchange for an energy deal off the cost. Meanwhile Israel was working on its pipeline deal with Cyprus and Greece, one that is linked to warming relations between Greece and Turkey as well.

Turkey is intensely hostile to the government of Cairo and they are on opposite sides in Libya. Would Turkey’s role in the Mediterranean cause Israel headaches regarding a pipeline that ostensibly crosses Turkey’s claims to an exclusive economic zone?

On May 14, Arab News ran a story about “Turkey, Israel thought to be in secret talks,” asserting that Turkey’s president was looking at a deal.

The evidence that Israel might be shifting was, according to the Arab News report, the lack of Israel’s support for a Cyprus-Egypt-France-Greece-UAE condemnation of Turkey’s “Illegal activities” and “expansionism” in Cypriot waters.

“Israel was not a signatory,” the article noted. Israel’s Foreign Ministry was quoted as saying it was “proud of our diplomatic relations with Turkey.”

A new piece of the puzzle emerged on Thursday with a report at The Jerusalem Post that Israel “learned from Hezbollah’s defeat at the hands of Turkey.” According to this report, Israel watched the fighting in Idlib in February and March between Turkey and the Syrian regime. Hezbollah units, including its “Radwan unit” were dealt a blow by Turkey.

Turkey has a conventional army along NATO lines. The Radwan unit was established to carry out covert operations against Israel.

Coverage in Turkish media of relations with Israel is usually hostile, but the recent reports show there is interest in this discussion. Several Turkish media outlets published reports on Gilad’s article or on converging interests in Syria.

There are other countries watching as well. Russia has amicable relations with Israel and Turkey. Russia and Turkey are able to work on joint patrols in Syria, even though they are on opposite sides and Turkey once downed a Russian jet. The arrival of Gabi Ashkenazi as Israel’s new foreign minister also piques interest about his potential outreach.

On the other hand, Turkish social media also claims Israel backs the opposite side in Libya and seeks to remind Turks about the Mavi Marmara. Yet, on another note some Turks online have pointed out that recent use of Turkish drones to destroy Russian-made Pantsir air defense in Libya was matched by Israel destroying similar systems in Syria, as if to say the two countries have similar experience.

It would be difficult to see how relations with Israel will improve considering the usual hostile comments from key officials and advisors around Turkey’s president Ibrahim Kalin, a key advisor, has been very tough on Israel.

Yasin Aktay, who often discusses Turkey’s foreign policy has also been very critical of Israel for years. One issue for Ankara was that reports at Middle East Eye indicated officials were hoping Benny Gantz might defeat Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and his could be a chance for an opening. Plans for Israeli annexation would be a major hurdle.

Nevertheless there are other factors involved. In October last year Turkey’s foreign minister appeared to understand Israel’s desire to prevent Iranian entrenchment in Syria and an Iranian corridor through Syria to Lebanon.

US Syria envoy James Jeffrey, who is very pro-Turkey, has also talked up recently the Iranian threat to Israel that exists in Syria. US officials have had difficulties with Turkey in recent years over a Turkish S-400 deal and also Turkish opposition to the US role in eastern Syria. But Israel-Turkey discussions would please those in Washington who think it might lead to Ankara taking a tougher approach on Tehran.

In terms of overall strategic views, Israel listed Turkey as a challenge in is annual military assessment in January. Former Defense Minister Avigdor Liberman appeared to have agreed with this view according to reports in the past. It has also been a long time since Israel and Turkish military officials officially met, one meeting was held on the sidelines of a NATO event in 2017, but it’s a far cry from pre-2009.

The COVID-19 crisis presents a further opportunity for healing. Al-Monitor reported sales to Israel from Turkey in April and Turkey has sent aid to Palestinians. Add it all up and there is much that could change, but there is a lot of inertia in the opposite direction.

Article first published on Jpost.

Seth Frantzman, a Middle East Forum writing fellow, is the author of After ISIS: America, Iran and the Struggle for the Middle East (2019), op-ed editor of The Jerusalem Post, and founder of the Middle East Center for Reporting & Analysis.