Iranian regime brutally attacks Ahwazis for demanding water access

by Rahim Hamid and Aaron Meyer

Local officials deployed dozens of security forces who responded to our demand for water with bullets and tear gas and beat dozens of us…

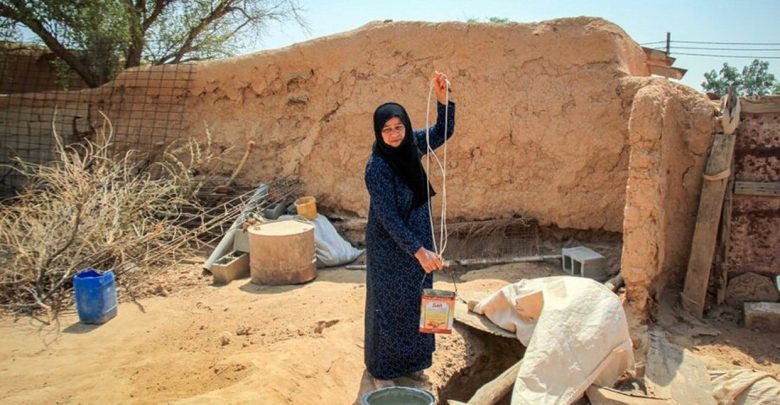

Iranian regime security forces last week reportedly brutally beat, injured and forcibly dispersed Ahwazi protesters for holding a peaceful demonstration in the Gheyzaniyeh rural area 40 kilometres east of Ahwaz city. The protest on Sunday May 24 was held due to increasing water scarcity, which has been steadily worsening for three decades and is now reaching a critical point at which water is increasingly either completely unavailable or is often so heavily polluted that it’s unfit for human consumption or even for livestock and other animals.

Iranian police met the protesters with a violent crackdown injuring a number of people and detaining many others.

Desperate locals in the area, which was once watered by rivers now dammed upstream and otherwise rerouted by the regime, are forced to wait for weeks until local officials approve their request for water essential for drinking, household use, and nourishing the livestock and date palm trees that provide their meagre sustenance. Their latest request brought only four tanker-loads of water for the entire population of 89 villages in the area, which came not from the regime but from fellow Ahwazis who came from across the region to bring water to the area after hearing about the regime’s abuses of the protesters.

With bleak irony, the protests and the regime’s customarily vicious response took place on ‘Al Quds Day’, when the Iranian regime commemorates its supposed solidarity with the Palestinian people, and its purported support for the oppressed and opposition to injustice globally. While the regime’s forces were quietly shooting Ahwazi citizens for demanding water, Iran’s leaders officially marked Al Quds Day by sending Iranian oil tankers to support Venezuela’s regime.

One despairing local, who gave his name as Mohammed, told Duruntash Studies Center (DUSC), “Imagine – 89 villages left without water for over 30 years, and the officials sent four tankers for all this population! Imagine how little water each household gets from that – some households have over seven members. We have domestic animals, livestock, palm trees to live on. We are desperate, stranded, just trying to keep ourselves and our poor animals alive!”

Regime forces were quickly deployed to these areas to crush the demonstration as protesters shamed the regime by pointing out that despite the Ahwaz area being home to 95 per cent of the oil reserves claimed by the Tehran regime, the people live in conditions of absolute poverty and struggle to survive without clean water, health services or decent schools. The Gheyzaniyeh region alone, whose 600-plus oil wells export around two million of barrels per day, contains 80 mostly interconnected villages with a total population of 26,000, most of whom are farmers or ranchers.

Although the area’s population exceeds 26,000, Iranian regime officials don’t recognise it as a county. The regime fails to make any distinction between rural and urban areas in Ahwaz and routinely refuses to provide its indigenous people with basic services. Meanwhile, in other, ethnically Persian areas of Iran, areas with populations lower than 10,000 are recognised as counties in their own right.

Mohammed added that the timing added to the sense of insult among locals angered by the regime’s abuses. “It was Eid al-Fitr; we’re fed up of this abuse and locals gathered to protest at this brutality and inhumanity, with young men blocking the roads leading to Ahwaz city, and Ramez and Amidiyeh to force the local officials to open their eyes and pay attention to our suffering. Instead, the local officials deployed dozens of security forces who responded to our demand for water with bullets and tear gas and beat dozens of us. We’re just grateful for the popular solidarity of other Ahwazi people from all areas who brought us water using their own cars.”

Another young local, Fouad Hassan, said: “The oil and gas that Iran sends to Venezuela’s refineries is from our area, Iranians hear and see the pleas of anyone in the world except our voices and send our wealth to them. Our area is two minutes’ walk from all these giant oil and gas industrial complexes – why don’t they want to bother themselves by providing water pipes to us, ignoring us while they send their oil ships thousands of miles to save Venezuelan refineries? The answer is, because we’re Arab and Iran only wants our oil. How many rivers does the Ahwaz region have? The Karoon, the Karkheh, the Dez…? So why does Iran spend billions building massive pipelines extending all the way to the Persian areas of Isfahan, Kerman and Yazd while it would take them less money to give us enough water to live?”

Another local youth, Mohsen Saleem, said: “I have a Master’s degree in oil engineering and I dreamed of being hired to work in one of these oil companies built on our lands five minutes’ walk from our villages to get there. But they won’t hire us [Ahwazis] – if we argue with them, they only humiliate us, mock us, saying ‘Instead of that, why don’t you go and improve your accent to make it bearable to hear you when you speak to us?’

“Every month we bury one or two of our locals here who’ve died of cancer. Few here live beyond 50, and everyone dies from various types of diseases caused by air pollution from these oil companies. This is land of oil Paradise for Iran and Hell for its Ahwazi people.”

Mohsen added, “The Ahwaz plain was once the most desirable area for farming. According to experts, however, exploitation of water, water diversion projects, and particularly the construction of several dams, has now caused the formerly arable plain to become a semi-arid land where agriculture is no longer considered a promising job.”

A female local also spoke with DUSC, saying “our villages are encircled by hundreds of oil pipes, I have a few sheep and goats and two cows. I used to have more but our lands don’t have any green grass now like they used to; our animals get stuck between the oil pipes and due to the scorching heat, they get stuck, many die from heatstroke. Our children want to play and they only have one option – to run around on these pipes in bare feet.”

A human rights activist from the city of Ahwaz said that despite Gheyzaniyeh being an Ahwazi area, many people in the city only heard its name for the first time when seeing it on the TV during Eid al-Fitr, when they saw the all-too-familiar images of an Ahwazi teenage protester shot by Iranian regime forces with blood running down his leg, while in the background they heard people yelling in protest over water shortages and thirst.

The pain and suffering of these local people have been hidden and ignored, like many Ahwazi areas, until recently when they protested. The regime responded by beating and shooting at the protesters, followed by predictable visits by regime officials claiming to offer sympathy. Yet their empty rhetoric slamming the Rouhani government for incompetence and mismanagement and unbalanced development was clearly intended merely to settle their internal political rivalries. Their self-serving attempts to co-opt Ahwazi suffering is not new to Ahwazis. It was just last year, in November, when suffering Ahwazi people in Ma`shour, an area very much like Gheyzaniyeh, protested at regime-endorsed systemic job discrimination and poverty by blocking the roads leading to petrochemicals. The protesters were massacred and burned in the nearby marshlands. Predictably, regime officials flooded the area after the massacre, promising to resolve the people’s suffering, and allocate a budget for building services, schools, and prioritising the employment of locals in the Petro companies. Those empty promises were never fulfilled, and are clearly nothing but meaningless rhetoric used by the regime as damage control following protests, and the regime’s inevitably violent and brutal response.

A common bleak joke amongst Ahwazis is that their only share in the region’s oil wealth is death, a result of the disproportionately high levels of cancer and respiratory diseases linked to the massive air pollution from the numerous oil and gas wells and the petrochemical plants which belch out acrid black smoke that often blankets the once-verdant region.

While Ahwazis’ homes and farmlands are routinely seized by the regime without warning or compensation by the oil and gas companies, the indigenous people are denied jobs at the oil and gas fields and the refineries. The same applies to the sugarcane farms and refineries in the region; since the regime launched its loss-making domestic sugar industry in Ahwaz in the 1990s, it has confiscated massive tracts of arable land beside the region’s three major rivers to establish sugar plantations, despite the climate being wholly unsuited to sugarcane farming, as well as building refineries to treat the sugarcane, which use the rivers’ water in the treatment process before belching out untreated industrial pollutants used in this process back into the rivers. As with the regime’s oil and gas industries, the displaced Ahwazi people are denied jobs in the plantations or refineries; instead, the regime constructs well-appointed settlements with facilities denied to the indigenous Ahwazis to attract ethnically Persian settlers from other areas of Iran who are persuaded to move to the region by the offer of homes, jobs and generous subsidies.

As well as poisoning the Ahwazis’ air, land and water, the regime has also cut off much of the remaining water supply by building massive dams upstream on all three of the main rivers that once made Ahwaz a regional breadbasket where farming and fishing were the main industries; these waters are now mostly rerouted to other, ethnically Persian areas of Iran, leaving Ahwaz suffering from horrendous drought and worsening desertification.

All these policies seem clearly intended to help the regime to depopulate the area of its indigenous Ahwazi population, a policy made clear by statements by the regime’s own officials which have led to regular protests by the long-suffering and oppressed Ahwazi people.

This area is one of the most deprived parts of the region, despite being home to many oil and gas companies exploiting Iran’s largest oil fields. The Karoon and Maroon Oil and Gas Companies and the National Oil Drilling Company are located in this area and the transit route of Iranian ports and Maroon and Razi Petrochemical Facilities also pass through it. Karun Oil and Gas Company produces more than one million barrels of crude oil per day, and the total daily production from oil wells of this area last year was estimated at two million barrels. However, Gheyzaniyeh and its surrounding areas are a showcase for economic, social and environmental problems, leaving its population destitute and suffering from wilful neglect and worse.

Khaled Karim, one of the locals says, “the local young people are denied any type of employment working these oil wells or for the companies that own them. Their farmlands are forcibly confiscated for oil drilling with almost no real compensation, the remaining lands turned into dead land unfit for farming after being wholly contaminated with the toxic substances used for oil prospecting.

“Our palm trees are dying from pollution and drought as the desperate locals, in order to survive themselves and to keep their livestock, are forced to give up on demanding the clean water pipes to their homes promised by regime officials. Instead, they have had to revert to their ancestors’ tradition of digging up wells, with the contribution of all the locals, so that all use it for their own and their animals’ drinking.

“But as oil drilling spread to their lands the water wells of the poor population got contaminated with oil. The water tastes oily and has led to the spread of intestine cancers among the majority of the population, including many children and has killed many of their animals that they were relying upon to make home dietary products to resist the hunger and poverty.”

According to Gheyzaniyeh’s district governor, “two-thirds of dust storms arise from this area. Oil companies, landfills, and recycling sites around the area cause smoke and the suffocating smell of garbage. The sandy unpaved and bumpy roads, and the lack of cultural and educational centres and school shortages are all part of the region’s long list of problems. “Water scarcity is one of the many problems of Gheyzaniyeh’s residents. Despite the lack of proper educational, medical and welfare facilities, they have for years considered access to pipeline water their most important demand, and for many years officials have been making empty promises to them.”

Gholamreza Shariati, the governor of Ahwaz, is one of those who have paid lip service, emptily promising to put an end to the suffering of locals due to water shortages. In addition to the protests in Gheyzaniyeh, Shariati and his wife are also involved in the corruption case of Haft Tappeh Sugar Company. Iranian media have reported that the director of the Haft Tappeh Sugarcane company, who was arrested for money laundering, embezzlement and the theft of millions of dollars, revealed in a closed-door trial that he had “paid $ 25,000 for the overseas trip of the governor of Ahwaz region and his family” and “donated $ 200,000” to his wife.

It must be stressed that the director of the Haft Tappeh and the governor of Ahwaz are the primary persons who issued orders to crack down on Ahwazi labour protests and strikes that were organised for not receiving their wages and their dire working conditions in Haft Tappeh Sugarcane company. Mr Shariati, who came to the governorship of Ahwaz four years ago, appointed by the first government of Hassan Rouhani, promised in January 2016 to solve the problem of Gheyzaniyeh’s lack of water within three months.

Two bills were passed at the time, one involving 25 kilometres of pipelines from the water facility of Karoon city to the Mosharrahat district of Gheyzaniyeh, and the second to build 55 kilometres of water pipelines in another part of the region to reach the rest of rural areas, which was to be jointly operated by the Oil Company and ABFAR Company (Rural Water and Sewerage Company). At the same time, the CEO of the National Company for the Southern Oilfields of Ahwaz spoke of the company’s special attention to the development of Gheyzaniyeh and promised cooperation and investment.

This documentary film is in the Persian language about the sufferings of one of the villages of Gheyzaniyeh area. Iranian reporter Ellahe Habib Elahi says: “I don’t know how do you define misery or how do you explain it? What are these pipelines? Are they merely oil pipes or misery pipes indeed? Please follow me to share with you some parts of that great misery.”

Masoud Tawakoli, Iranian reporter says: “This is just one of the seven hundred of oil wells of Gheyzanieh area of the Ahwaz region.”

Iranian reporter: “We are here with Mr Baledi, the chief/elder of the Rozaneh village that is one of Gheyzaniyeh rural area; Mr Baledi will talk about some of the shortcomings and the deprivations of the village.”

Baledi, the headman of the village says, “here the village population was around 1500 people which was more than 300 families. They were forced to immigrate due to lack of the most basic essential facilities and currently they are less than 45 families. In total, approximately 250 remain in this village, although the number diminishes with each day. These people are continuing immigration due to the difficult life situation.”

Reporter: “Which companies are based around here?”

Mr Baledi: “Different companies as you can see like Karoon Oil and Gas company’.

Reporter: “Of course the companies that have been established and worked here for more than 50 years have had to provide necessary facilities for people of the surrounding area. Which facilities have they supplied the villages with, given that they had focused on operating oil prospecting here for the last fifty years?”

Mr Baledi: “As you can see they haven’t done anything, they did not provide us anything in all the 50 years since the Oil has been discovered and the oil companies have been established in this region, but just to mention the new area govern, Mr Hashemi has tried hard to persuade the companies to supply the local population with clean drinking water, and they promised to supply two tankers of drinking water in the summer !!”

Reporter: “Please explain to us about the hygiene and the health services of the area, at least do you have a health centre”?

Mr Baledi: “There are no basic health services in the area. People have to go to the city for any treatment or doctors’ visits, even just for shots.”

Local elderly woman: The people who get sick here pass away in winter due to lack of facilities. This is our land and homeland, but we suffer from unemployment and the companies are reluctant to hire our people. All the labour recruits are from other cities.”

About Schools

Local young man: “All the primary students first to fifth grade just study in the same classroom and with the same teacher, the school is only one classroom. It is tough for them to tolerate this condition. These conditions have driven them to drop out of school because most of their parents are unemployed and unable to support them financially for transportation so that the children go to urban areas for education. Completing education at least until high school diploma takes a few years, I mean it is not one or two years. Also, parents cannot afford other necessities of educational needs and requirements even if these children wish to continue their education.”

“Even the local young people get their high school diploma, the oil companies will never hire them in these companies even as a doorman or guard. If we apply for jobs or go to the company to file a complaint, they never allow us to enter the entrance gate, let alone to talk to the authorities about the unemployment and the difficulties we suffer from.”

“The bigger problem than unemployment is the lack of clean drinking water in the area. We have to go 40kms to Ahwaz to buy some drinking water with an affordable price considering that some people haven’t got any vehicle to travel with.”

Reporter: So, the water that provided to the area by tankers is not safe to drink?

The local young man: “No, it is not safe to drink it, it is just for washing, and the tankers do not come regularly and keep us waiting for a long time. We have to buy barrel water from the city. The concerned officials should take action and have a sense of responsibility towards us. We suffer from thirst and lack of electricity in such warm weather, let’s forget about employment, we do not want job opportunities.”

Reporter: “Have the authorities or MPs come to visit the region?”

The local young man: “Yes, they have come, and they know about the problems we suffer from but unfortunately have done nothing to help to ease our sufferings! About the roads, we have just one dirt road which is totally ruined, and we cannot drive on such road on rainy days, and we can’t take our patients to the hospital in winter days.”

Reporter: Yes, that’s right, the road is ruined, and if there was no guide with us, we were unable to find the village.

The local young man: “yes, there are no signs nor signs to direct drives to the correct routes around the village.

We have got just one power transformer in all the area. The weather is too hot here, and we are about 50 families. At noon as the temperature reaches its highest points, the power goes out frequently making our life more miserable and unbearable.”.

Another local man: “I have had some livestock, and all my domestic animals perished due to lack of water and drought.”

The headman of the village (Mr Baledi): “What you see here is a seasonal spring that fills with water during rainy days, and the villagers who are besieged with oil wells use it as drinking water for themselves and their domestic animals. Its water is totally unhealthy and lethally contaminated.”

Reporter Ellahe Habib Elahi: “we are responsible, and we will be held accountable in front of Justice.”

More videos from Gheyzaniyeh area

The following video shows that after nearly two decades of Gheizaniyeh residents’ attempts to get various Iranian departments to solve their problems including the water scarcity, all attempts were unsuccessful. Finally, without other options, residents closed entry to the Ahwaz capital by obstructing the major Omidiyeh highway with stones. It was a move intended to get their voices heard and grievances acknowledged by administrative leaders. But instead, Iranian regime forces fired live bullets into the demonstrators, injuring some of them and arresting others.

The second video depicts the miserable circumstances that Gheizaniyeh residents are suffering from. The residents are saying that every two weeks a single water tanker comes to the village. The area has no infrastructure, no schools, unpaved non-asphalt roads, no mosque and all the young are unemployed. One resident said we are deprived of all essential life necessities.

The third video shows one of the young men from the Gheyzaniyeh area speaking about their suffering in this area that has had no water for more than a month. He said that “we reached out to all Iranian departments, but they did not respond to us. The Iranian officials do not pay attention to us, and the only way that they look at us is when we close the main roads; then they will shoot us by live bullets and either kill or injure us.”

One young man, whose name is withheld for his safety, says, “I am broken. I married two years ago, and my wife was pregnant. In her last few days, she had sudden bleeding and her water broke. Because there is no basic health centre anywhere near us, I had to take her to Ahwaz city, 45 km away, but my baby died.

“Iran can send our oil everywhere, and it can easily send our water to Iranian areas, but why do they not want to give us basic services? We are not wondering; we know the answer, because we are Ahwazis. Ali Khamenei is trading with Palestinians, and says Muhammarah is a second Quds. It is not fair; Muhammarah is occupied, like all Ahwaz areas. Iranian brutality can be seen when you visit any Ahwazi area. The war ended three decades ago, but Muhammarah still carries its ravaged destruction on its sleeve like all Ahwazi areas. Our suffering is beyond the concept of colonization and occupation. While Israel is helping Palestinians amid COVID-19, Iran deprives Ahwazis of water access and medical care.”

The fourth video shows an old man, saying that “whenever we talked about our need for drinking water, the official in Gheyzaniyeh quickly labelled us Wahhabis. We are not Wahhabis, we are only demanding drinking water, nothing else. Anyone saying otherwise is not telling the truth; we just want water.

The last video shows the visit by the representative of the Iranian supreme leader to a child who had been shot by Iranian occupation police forces during protests. Looking at the child’s face, it is clear that the visit was simply to suppress Ahwazi rage, and likely to threaten the people as the regime did following the Ma`shour massacre. Tellingly, there was no follow-up meeting to address the people’s demands.

Ruled by an uncaring and hostile regime, Ahwaz has seen its farmland turned to desert, its waters pumped out and diverted, and its oil resources ripped from the ground. In the throes of drought, the people’s protests have been met with live fire and crocodile tears, even as their pleas go unheard. It is clear that the ruling regime has no problem seeing them die, but will the world finally take notice and demand that they be given basic necessities to survive?

Article first appeared on Duruntash Studies Center.

Rahim Hamid is an Ahwazi author, freelance journalist and human rights advocate. He tweets under @Samireza42.

Aaron Eitan Meyer is an attorney admitted to practice in New York State and before the United State Supreme Court, and a researcher and analyst. He has written extensively on lawfare, international humanitarian, and human rights law. He tweets under @aaronemeyer.